Americans of all backgrounds are working together to end the pandemic. Dedicating any energy toward frivolous prejudices against Asian Americans is a wasted effort that undermines the battle against COVID-19.

America’s most famous immigrant raises her torch high above New York Harbor, embodying the nation’s core values of freedom, justice, opportunity, compassion, and the pursuit of happiness. For 134 years, Lady Liberty has symbolized these noble ideals for her fellow Americans and for all those who desire freedom. Through wars, a depression, pandemics and times of national outrage, she has reminded us that we aren’t bound by blood or soil but the values that have allowed the United States to thrive.

Yet we struggle to live up to these ideals.

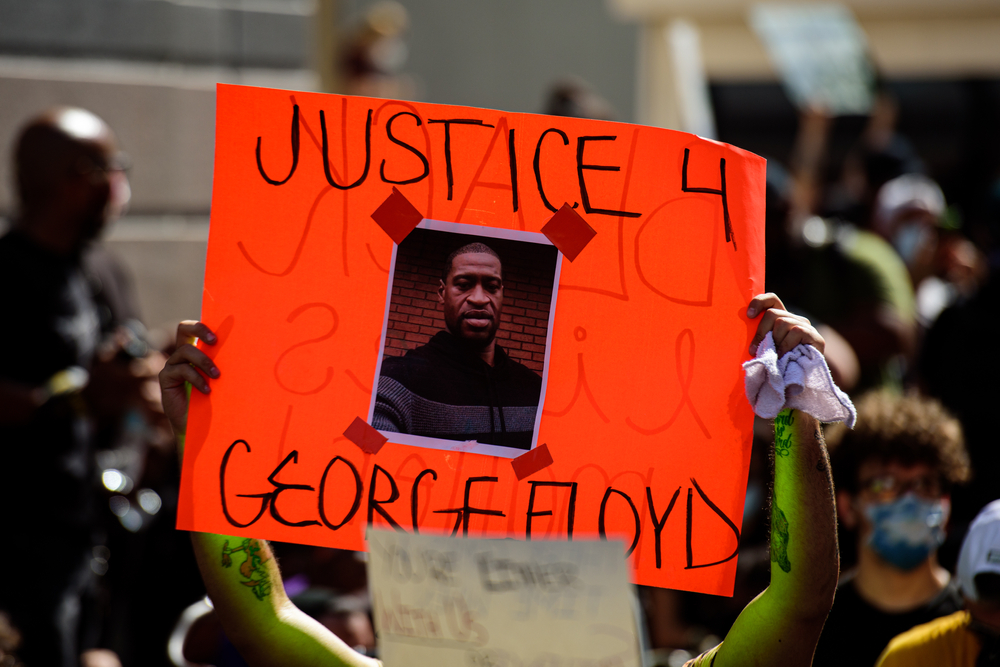

At the same time our country is wrestling with systemic issues of racial injustice and inequality against African Americans brought to the forefront of the national consciousness by the murders of Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, fear of the COVID-19 virus has sparked discrimination against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPIs) as well as broader immigrant communities. Meanwhile, African Americans and Latinos are disproportionately getting sick and dying from the virus.

These tragedies strike to the heart of our national story of a people who look, believe and act differently, striving together toward the idea that we all deserve to be free, to live in peace, and to chart our own course in life. At its core, America stands for diversity – a great ethnic, cultural, intellectual patchwork quilt stitched together by those shared ideals. That diversity is our strength. And that’s why incidents of violence against any American hurt us all.

At its core, America stands for diversity – a great ethnic, cultural, intellectual patchwork quilt stitched together by those shared ideals. That diversity is our strength. And that’s why incidents of violence against any American hurt us all.

Attacks against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders grew so bad in the early days of the coronavirus that the Asian Pacific Policy & Planning Council launched a website to track them. In its first two weeks, the STOP AAPI HATE website received over 1,100 reports of physical assault, verbal harassment, and shunning of Asian Americans.

Since then, reports have come from 45 states and Washington, D.C. The FBI described a March 14 incident in Midland, Texas, in which three Asian American family members, including a 2-year-old and 6-year-old, were stabbed: “The suspect indicated that he stabbed the family because he thought the family was Chinese and infecting people with the coronavirus.”

U.S. national security leaders and the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights have also raised the alarm about the severity and frequency of hate crimes and race-based harassment against Asians and the AAPI community. Twenty-eight U.S. senators sent a letter to the President expressing similar concerns, though, unfortunately, no Republican senators took the opportunity to express solidarity. It is imperative upon all leaders — across the political spectrum, public and private organizations, and at the local, state, and national levels — to not only condemn bigotry but to model responsible language and behavior.

There is no justification for violence and abuse, and calling COVID-19 the “Chinese virus” enables this type of reprehensible behavior. What is even more insidious is the subtle assumption that Chinese Americans or Asian Americans in general are not truly “American” – that they are outsiders and not woven into the fabric of this country. Nothing could be further from the truth.

That’s why words matter; the World Health Organization’s disease-naming conventions avoid terms that identify people or locations for good reason. We must encourage greater sensitivity to the impact of words in the public sphere. This starts with individual and institutional responsibility and leadership and extends to the media, our organizations and our leaders.

It is imperative upon all leaders — across the political spectrum, public and private organizations, and at the local, state, and national levels — to not only condemn bigotry but to model responsible language and behavior.

Using more neutral language to refer to the virus doesn’t by any means absolve the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) for overseeing what is, according to Freedom House, one of the least free countries in the world. Nor should it prevent our leaders from confidently condemning Beijing’s human rights abuses and systematic efforts to destroy institutions like free media that promote transparency and government accountability. There is a difference between legitimately criticizing the CCP’s brutal efforts to obscure COVID-19’s impact in China and vague rhetoric from our leaders that incites hatred against Chinese Americans or Asians generally.

Current events highlight the pitfalls of sacrificing precision in order to create “bumper sticker” talking points that crudely shape public perception for political purposes. Sadly, this is a tactic used across the political spectrum, but that doesn’t excuse it. The American people should hold their leaders accountable on such issues, regardless of political affiliation, and not allow “whataboutism” to compromise principles. And while it’s unrealistic to attribute a single cause to any rise in discrimination related to the global pandemic, having clear, consistent, empathetic, and trusted leadership is a factor.

While such leadership qualities foster stability in any time, their importance increases in a crisis because societal tensions are higher. Used together, they steer frightened and frustrated people away from fear, suspicion, and paranoia.

Look at the example of President George W. Bush following the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks. Angry people were channeling their rage through unacceptable violence against Muslim-Americans. Six days after 9/11, President Bush appeared at the Islamic Center of Washington, D.C., flanked by Muslim American religious leaders, and offered a strong rebuke of this persecution.

In doing so, President Bush stripped away any cloak of “patriotism” that some individuals might have used to justify bigotry and violence, stating, “Those who feel like they can intimidate our fellow citizens to take out their anger don’t represent the best of America, they represent the worst of humankind, and they should be ashamed of that kind of behavior.”

Those who feel like they can intimidate our fellow citizens to take out their anger don’t represent the best of America, they represent the worst of humankind, and they should be ashamed of that kind of behavior.

President George W. Bush, September 17, 2001

Unfortunately, leaders aren’t always quick to acknowledge and repudiate violations of our founding principles.

More than 40 years after Japanese Americans – having been stripped of their dignity and rights as citizens – were released from World War II-era internment camps, President Reagan offered reparations from an ashamed nation. He stated: “We gather here today to right a grave wrong… 120,000 persons of Japanese ancestry living in the United States were forcibly removed from their homes and placed in makeshift internment camps. This action was taken without trial, without jury. It was based solely on race…”

The examples of 9/11 and Japanese internment camps have enduring legacies that highlight a recurring tragedy in our history, which is why it’s also valuable to acknowledge and appreciate the leadership shown by Presidents Bush and Reagan as ways to learn and grow from our mistakes.

We have been susceptible to devaluing fellow citizens based on their physical characteristics and heritage. In essence, their “Americanness” is obscured because of their appearance. What does an “American” look like, anyway? And does that description change with fluctuating political and socioeconomic factors?

On one hand, historical experiences tell us the answer to that last question is, unfortunately, “sometimes, yes.” However, there’s a deeper, more enduring answer about what constitutes an American that is rooted in our founding documents and our tradition of self improvement.

Our Constitution has evolved over two centuries to guarantee fundamental rights and liberties to all Americans; no doubt our citizens and democratic institutions will continue refining it. But the preamble clearly states that “we the people” wish to “form a more perfect union” by acting to “promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity.” A more perfect union requires unity, inclusion, empathy, and understanding of our common humanity despite differences. Subjecting Americans to violence and intimidation based on their ethnicity or perceived heritage is a betrayal of that pledge.

Remember that it was 20,000 Chinese immigrants who built the transcontinental railroad. The U.S.-born children of Japanese immigrants made significant contributions to the agriculture of the western United States, improving upon the sophisticated irrigation methods introduced by their immigrant ancestors and enabling the cultivation of fruits, vegetables, and flowers on previously marginal lands. We could list major contributions by each and every group of Asian immigrants that came to this country, and it still would not do justice to what they have done to make America what it is today.

Unfortunately, when it comes to disease, we fall back on the temptation to discriminate. Yellow fever was associated with Germans in the eighteenth century, cholera with the Irish in the nineteenth century, and Haitians with AIDS in the twentieth century.

We must learn from our mistakes. It is the only way we will all get through this together, as Americans, as a country.

Moreover, America’s example has power beyond its borders. The world watches us. When we fail to live our principles of liberty and justice by discriminating against others, it makes it more difficult to dissuade allies and adversaries from doing the same. As a global community, we must actively fight any inclination to blame the innocent for political gain. That will not help us fight a pandemic that knows no national boundaries. What will help us is science, education, and listening to public health officials who know best how to beat COVID-19. Discrimination distracts from the spirit of local, national, and international cooperation required for victory.

The world watches us. When we fail to live our principles of liberty and justice by discriminating against others, it makes it more difficult to dissuade allies and adversaries from doing the same.

Human nature being what it is, bigotry may never disappear completely, but we can always control our own actions. Our personal examples can inspire others. It’s incumbent upon every American to recognize and call out discrimination if and when we see it in our communities and our country.

This shouldn’t be construed as a call for self-righteousness or an effort to suggest that one group’s hardships discount the problems of another. On the contrary, it’s about reminding our fellow citizens and ourselves, not through judgement but through our compassion for marginalized communities, that every person is created with innate human dignity that must be respected and protected equally under the law.

Expanding our social experiences can help this effort by improving our perspective on different people and viewpoints. This isn’t some idealistic pipedream. Americans exemplify this way of living every day through participation in religious organizations, civic clubs, intramural sports leagues, community theater, homeless shelters and food pantries.

The Bush Institute’s domestic and international leadership programs offer another good example. They bring together men and women from diverse ethnic, religious, ideological, and geographic backgrounds to engage in person over six months. The experience forces participants to consider their perceptions of different groups versus the reality of interacting with a flesh-and-blood human being. Often, they share similar hopes, fears, and interests; the reality proves better than the perception.

Admittedly, this type of engagement isn’t easy. It requires courage, authenticity, vulnerability, and practice. But as these leadership programs demonstrate, it starts with a willingness to talk and listen; the reward is developing foundational trust upon which mutual respect and friendship are built.

Immigrants and their descendants want to share in that experience too. Despite challenges posed by discrimination, people from all over the world choose to make the United States their home. They still believe in America’s dual promises of freedom and opportunity. In doing so, they assume different roles that help our country thrive socially, culturally, and economically.

Almost a fifth of the American workforce is comprised of immigrants. This includes 17 percent of grocery store clerks, 18 percent of food delivery drivers, 19 percent of truck drivers, 30 percent of doctors, and 15 percent of nurses. COVID-19 has exposed how much we depend upon these everyday heroes, and how much they contribute to the health of our society and economy. We must do more to support them, including promoting comprehensive immigration reform to meet the needs of our 21st Century economy.

The kaleidoscope of Americans working together to get through this pandemic is a point of pride. Meanwhile, any energy dedicated to frivolous prejudices is wasted effort in the battle against COVID-19. As an individual, you don’t have to solve bigotry in America, you don’t have to judge others for their mistakes, but you can control how you demonstrate compassion for people who are different from you (especially when it’s inconvenient, hard, or both).

Almost a fifth of the American workforce is comprised of immigrants. This includes 17 percent of grocery store clerks, 18 percent of food delivery drivers, 19 percent of truck drivers, 30 percent of doctors, and 15 percent of nurses. COVID-19 has exposed how much we depend upon these everyday heroes, and how much they contribute to the health of our society and economy.

During this difficult time, let each of us take seriously our personal responsibility to represent the best of America, respect human dignity, and live the principles embodied by Lady Liberty. We can each model the traits of empathy, clarity, consistency, and trust that are essential to leading in our communities. In doing so, we can thank a local grocer, applaud a medical professional returning from their shift, or tip our DoorDash driver a little more – because immigrant or not, they’re fellow Americans serving the country we all love.