George W. Bush Institute and Center for the Study of Democracy

Strategic Corruption: Russia in Europe

About the series

This three-part series details Russia’s strategic corruption in Europe and provides recommendations for European policymakers to stop Moscow’s harmful practices that seek to destabilize the West.

Policy Recommendations:

- Europe must reconfigure trade and investment patterns to reduce strategic vulnerability, privileging allies over adversaries.

- European countries should incorporate into their economic security strategy more financial transparency tools along with robust anti-money laundering mechanisms, such as foreign investment screenings, and enforcement mechanisms that target and prosecute Russian networks and intermediaries.

- Governments and/or publics in European countries should require companies that maintain Russian operations to disclose their rationale and risk assessment, raising the reputational and legal cost of engagement.

- Europe and its democratic allies should prioritize secondary sanctions while considering lowering the 50% beneficial ownership rule.

- The European Union should support local and investigative journalism and civil society organizations that probe Russian corruption and behavior.

1

INTRODUCTION

Vladimir Putin’s use of corruption has become endemic to Russia’s government, operating in a manner that is both insidious and concerning. The Kremlin has weaponized corruption to make it more sophisticated than traditional models, using it to build and maintain patronage networks that keep the Kremlin in power. This system has turned corruption into a stabilizing force in Putin’s autocracy, where any opposition is met with imprisonment or worse, such as in the case of the late opposition leader Alexei Navalny.

Russian corruption operates to create a monopoly of political power in the Kremlin, controlled by Putin and his cronies. Economic crimes in Russia span the typical activities associated with corruption – such as embezzlement, bribery, and kickbacks – as well as more advanced techniques, such as the mobilization of oligarchs, state-owned enterprises, and organized crime. Within these criminal acts are elements that build leverage for Putin, including creating financial dependency and the weaponization of Russia’s private sector, which political loyalists and oligarchs have effectively captured. In essence, the Kremlin has built a state capture system of governance, using law enforcement not to uphold the rule of law but to subjugate any private or civic entity or person to the extractive institutions created for the enrichment of the Kremlin-backed elite.

And yet, it is not enough for the Russian regime to restrict this behavior to within the country’s borders.

Rather, Russia uses its influence as a strategic tool to destabilize other countries and compromise Western institutions. Pro-Kremlin oligarchs have established networks throughout Europe using Russian capital to acquire strategic assets and sectors, thereby creating opportunities to capture control of Western institutions and political decision-making processes. Russia has sought to weaponize all of its public and private foreign policy instruments and channels globally.

Using the same criminal methods as in Russia, Putin has extended the reach of corrupt activities into neighboring European countries and even globally. This tactic, termed strategic corruption, relies on the same strategies used in Russia to manipulate the power dynamics in European politics and policy in favor of Moscow by weakening democratic processes and establishments. It seeks to indebt beneficiaries of Kremlin “generosity” to Moscow, leaving them vulnerable to Russian pressure and exploitation. Oligarchs indebted to the Kremlin establish networks in pursuit of profit. However, due to their dependency on Moscow, these networks become instruments of Russian foreign policy.

Consequently, strategic corruption has become an instrument for Putin to undermine the security sector in conflict-affected areas, fueling instability in the European continent’s security apparatus and making it vulnerable to Russian influence. The Kremlin’s state capture model seeks to monopolize any area of influence, creating networks in the economy (mostly energy and finance), media, church and culture, and even organized crime. However, within Europe’s security apparatus, Russia’s use of strategic corruption leverages established networks with ties to the Kremlin to capture considerable influence to undermine the sovereignty and integrity of institutions and policies. Structures established by Russian intermediaries cultivate alternative systems capable of shaping policy and security outcomes throughout European states. This makes European nations susceptible to Russian coercion through establishments under the Kremlin’s influence.

This report will examine the relationship between Russia and strategic corruption through a security lens. Using cases of Russian activity in Europe’s security sector – which encompasses all the institutions and actors responsible for managing security within a country – this paper will look at how the Kremlin advances its strategic ambitions by utilizing corruption to undermine regional security. Furthermore, it will explore the consequences of Russia’s malign activity by using the illegal Russian military occupations of Georgia and Ukraine as case studies, making the case that Moscow’s corruption has evolved from an instrument of national strategy into a global weapon.

2

METHODS OF CORRUPTION

There are three main pillars supporting Russia’s use of strategic corruption. First, Russia relies on its control of key industries – primarily within the energy, media, telecommunications, metallurgy, defense, and finance sectors – to create dependencies that become pressure points for Russian policy objectives. Second, it relies on bribery, patronage, and kickbacks for key figures and political parties that support or align with Moscow’s ideologies to build anti-Western sentiment and disrupt political processes. And, lastly, Russia mobilizes clandestine financing and illicit financial flows tied to Russian-linked businesses, oligarchs, and organized crime to obtain influence in the security sector, which it can then use to build support for pro-Russian politics and policies. While the aim of such corruption is not enrichment, it does contribute to Russia’s efforts to erode European sovereignty and create leverage against European states.

One last point worth noting: Despite rhetorical trashing of the West by the Kremlin and its propagandists, Russian elites have historically trusted institutions in the West more than they do those in their own country, making the West the preferred guardian of their ill-gotten gains. The use of strategic hypocrisy is a Kremlin tactic to build disdain for Western institutions, while simultaneously making use of these very institutions to safeguard their assets in the West.

a. SECURITY INSTITUTIONS

Russia has long used positions on the boards of its state- or oligarch-owned major companies to lure Western political figures on the federal, state, or local levels into networks of influence, which have then been used to exert undue control on security institutions. This corruptive influence has often been underpinned or enabled by extremely lucrative Kremlin-facilitated investment opportunities in Russia’s vast state-regulated industries.

In 2021, Karin Kneissl, Austria’s former minister of foreign affairs who is linked to the country’s far-right Freedom Party (FPÖ), was nominated to the board of Rosneft – Russia’s state-owned oil company – after her term in office ended. The FPÖ has been a prominent advocate for pro-Russian policy in Austria and signed a cooperation agreement with the ruling United Russia Party in 2016 under the leadership of former Vice-Chancellor Heinz-Christian Strache. Following the announcement of the agreement, Strache denounced international sanctions on Russia over its annexation of Crimea, calling them “damaging and pointless.” Once the second-highest-ranked politician in Austria, Strache was filmed offering attractive government contracts in exchange for financial support during his own campaign from a woman whom he presumed to be the daughter of a Russian oligarch. The investigation into this is now recognized as the “Ibiza Affair.”

In 2024, Austrian intelligence officials revealed that a 2018 raid on Austria’s intelligence agency was actually a Moscow-led operation supported by the FPÖ to install new leadership under the Kremlin’s influence. The operation, which was facilitated by Jan Marsalek, an Austrian citizen and member of the GRU, Russia’s military intelligence agency, fed false information to the FPÖ alleging that Austria’s domestic intelligence service was investigating the political party. The raid was approved by the then-FPÖ-controlled ministry of the interior. During the raid, Austrian police seized over 40,000 gigabytes of classified information sent to intelligence agencies, including from the United Kingdom’s MI5 domestic security agency.

Russian support for anti-Western political parties is also evident in Germany through the Alternative for Germany party (AfD) and Sahra Waenknecht Alliance (BSW). In 2024, prosecutors in the German state of Bavaria conducted a money laundering investigation on an AfD lawmaker for receiving payments totaling €20,000 ($23,000) from people close to Putin. Other reports indicate that mysterious donors paid for several leaders within the AfD party to fly to Moscow. Much like the AfD, the BSW has been used to act as the Russian arm in the German parliament to build anti-NATO stances, stop military support for Ukraine, and criticize German military initiatives like the Command Task Force Baltic, which is leading NATO’s maritime operations in the Baltic Sea. Within Germany, Moscow has also sought to win favor with high-ranking political figures, as seen in the case of Gerhard Schrӧder, who sat on the board of Rosneft alongside former East German Stasi officer-turned-businessman Matthias Warnig before stepping down in 2022.

Russia’s support for political parties like the AfD and FPÖ reflect how Moscow uses alliances to shape NATO and EU security policy from within. Political party capture and intelligence penetration become parallel instruments of strategic corruption, operating in tandem to undermine Europe’s security sector.

Moscow has used similar methods of financial support for pro-Kremlin parties throughout Europe to support Russia’s security policies and annexation of Crimea, a 2023 report by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project shows.

Along with support for pro-Russian political parties, the Kremlin relies on clandestine financing to penetrate security agencies. In 2021, Peyman and Payam Kia, brothers living in Sweden involved with Swedish security and counterintelligence services, were arrested for aggravated espionage aiding Moscow. Swedish courts stated, with supporting evidence, that the brothers operated on behalf of the GRU after receiving a 550,000-Swedish krona ($59,000) payment from Russia. Sweden has been mostly immune to the Kremlin’s influence. However, the case of the Kia brothers demonstrates how even countries like Sweden remain vulnerable to intelligence penetration and influence despite having minimal trade reliance on Russian goods.

In 2022, Sergey Skvortsov and Elena Kulkova, a Russian immigrant couple living in Sweden, were arrested for gathering intelligence secrets on behalf of the GRU. Swedish authorities found that the couple owned several companies in the information technology security industry, with links connecting them to firms based in Cyprus and controlled by a retired GRU colonel.

In Germany, a similar case saw a high-ranking intelligence officer charged with treason for selling classified German information on the war in Ukraine and the Wagner Group to Russia for the sum of €400,000 ($465,000), demonstrating a pattern of Russian efforts to weaken Europe’s intelligence resilience. Such transactions have been enabled by a wider system of permeability of Russian business in the highest echelons of German industries.

b. JUDICIAL SYSTEM AND MULTILATERAL INSTITUTIONS

Following Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea, the European Court of Human Rights suspended Moscow’s voting rights. A member of the court since 1996, Russia had become a major financial contributor to the organization, providing €33 million ($38 million) a year at the time of the Crimea attack. Three years after the court’s decision to suspend its voting rights, Russia discontinued its payments, leaving a financial burden on the council too heavy for the body to carry. In 2019, facing budgetary issues, the court decided to restore Russia’s voting rights despite its occupation of Ukrainian territory.

However, Russia’s strategy of using financing to influence court systems extends beyond multilateral institutions.

Demonstrating how Russia uses corrupt money to influence the judicial system in European nations, Moscow obtained information on extradition requests for Russian nationals by bribing Eleni Loizidou, the former deputy attorney general of Cyprus. Leaked emails show how Loizidou shared information with Russian officials on loopholes that could create outcomes favorable to Moscow in certain cases.

Loizidou directly interfered in overturning or appealing decisions against Russian interests in several cases. In 2007, Natalia Konovalona, a lawyer affiliated with the now-defunct Russian oil company Yukos, fled Russia seeking asylum in Cyprus, and Russia submitted an extradition request. The Limassol District Court in Cyprus denied it, stating that the proposed extradition was a politically motivated move by Moscow. Loizidou appealed the decision of the court, which ultimately overturned its decision and sent Konovalova to Russia, where she faced a five-year jail sentence after being tried and found guilty in absentia in 2013.

The leaked emails also found that Loizidou promised Russian officials to extradite a member of Alexei Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation arrested in Cyprus once Moscow submitted the appropriate paperwork. In a 2013 email exchange, Loizidou thanked Vladimir Zimin, a member of the Russian Department of International Legal Cooperation in the Russian Prosecutor General’s Office, for a paid trip to Moscow. These cases come against the backdrop of a deep-reaching Russian business presence in Cyprus, which has entangled in its networks political leaders in the highest echelons of power.

The influence pro-Russian oligarchs and officials can have on European judiciaries was evident in a separate example researched by the U.S. Institute of Peace: Corrupt actors had effectively captured the system in Ukraine’s District Administrative Court of Kyiv (DACK) when it was operating under the supervision of former pro-Russian Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych. Since then, DACK has been used to defend and promote pro-Russian ideals and decisions. Some of the court’s rulings include blocking reform for Ukraine’s military, prohibiting protests that led to several arrests by Ukrainian law enforcement, and an attempt to reinstate Yanukovych as president.

Following the Euromaidan revolution – a wave of demonstrations and civil unrest in Ukraine in 2013 and 2014 – Oleg Tatarov, a pro-Kremlin official in the Ministry of Internal Affairs, forfeited his position. Though he claimed that he voluntarily left, it is unclear that the decision was his own. Tatarov filed a lawsuit requesting that DACK reverse his removal from the position, and, in December 2016, the court complied.

Separately, a recent Radio Free Europe investigation determined that

the Kremlin established a network of members in Putin’s inner circle within the Organization of Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), a key international organization in the field of security and human rights. Former Russian diplomat Anton Vushkarnik, who is believed to be employed by Russian intelligence, and Daria Boyarskaya, Putin’s former translator, have been linked to sensitive positions within the cooperative.

Vushkarnik was nominated by Moscow in 2017 to represent Russia in the Strategic Policy Support Unit and served as a member of the Cooperative Security Initiative and senior advisor within the OSCE, the latter of which the Russian Foreign Ministry financially covers. The secretary general responsible for launching the Strategic Policy Support Unit and Cooperative Security Initiative, Thomas Greminger, stated that a solution to the conflict in Ukraine ”can include temporarily ceding territory to Russia.” Vushkarnik’s presence in Vienna, where the OSCE is based, is marked by his luxury vehicle with a license plate used to identify Russian diplomatic missions in Austria.

Boyarskaya, who frequently accompanied Putin and Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov on trips during her employment with the Russian Foreign Ministry, has been an employee of the OSCE since 2021. Her rapid promotion to the head of the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly’s Liaison Office in Vienna in the same year has been criticized by members of the organization, who say that the hiring and promotion process is opaque. In her work as a translator, she has also been accused of leaving out key details that favor Russia. Boyarskaya had access to operational contacts across Europe and Asia in this role and facilitated official OSCE visits and supported electoral observation missions. According to the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly website, Boyarskaya still works with the organization as a senior advisor, including to the secretary general.

3

CURRENT EXAMPLES

Actions in Georgia and Ukraine clearly illustrate how Russia is using strategic corruption to weaken Europe’s security sector. Both countries have been impacted by malign influences tied to Moscow, either directly or indirectly through other countries. Putin uses the same methods outlined in the previous section to undermine industries in both countries and, consequentially, throughout all of Europe.

The cases of Georgia and Ukraine show how the Kremlin also often resorts to corruption to gain influence in foreign judicial systems, eroding the integrity of the courts. This judicial capture is a deliberate Kremlin method used to neutralize checks on Russian intermediaries, legalize illicit financial flows, and ensure impunity for proxies. This strategy turns courts into a security liability, shielding Russian networks and delegitimizing democratic institutions.

a. GEORGIA

Russia occupies 20% of Georgia’s internationally recognized territory since invading in 2008. Moscow’s occupation is accompanied by a recent backsliding in Georgia toward authoritarianism and pro-Russian policies under the influence of oligarch Bidzina Ivanishvili, who made his fortune in Russia. The recent political developments in the increasingly Kremlin-aligned Georgian government are concerning and reflect Georgia’s struggle to decouple from its relationship with Russia since its independence, despite having a population that remains strongly pro-Western.

Between 2005 and 2006, Russia began pressuring Georgia to transfer to Moscow control of pipelines transporting gas from Russia to Georgia and eventually Armenia. Moscow’s growing ability to coerce Georgia was not an immediate concern for Western policymakers at the time. They were more focused on the significance of energy reliance issues. However, there was some worry that the transfer of control to Moscow would worsen security risks in Europe because of closer links between Russia and Iran and Turkey.

And yet, Georgia never ceded to Russian pressure to give up control of its pipelines. Following Tbilisi’s refusal to forfeit ownership over the gas route, several explosions on Russian pipelines severed the gas transport destined for Georgia, causing heat and electrical shortages in the country, which were also exacerbated by an explosion on Russia’s electricity cable to Georgia. Then-Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili denounced Russian claims that the blasts were under criminal investigation, citing them as an attempt by the Kremlin to apply economic and political pressure to Georgia to give up control over the pipelines.

At the same time, Russia was providing military and financial support to separatists in the South Ossetia and Abkhazia regions to further sow instability across Georgia. The two ethnic regions are strategic for Putin and his intent to block the country from joining the EU and NATO. Furthermore, gas pipelines that originate in Russia and flow through South Ossetia connect Georgia to energy trade from Azerbaijan to Turkmenistan and Turkey. This cuts the market off from direct links with Russia. However, more critical from Russia’s security perspective is Abkhazia, which contains more than half of Georgia’s Black Sea shoreline.

Tensions soared following the 2003 Rose Revolution in Tbilisi, a nonviolent movement protesting electoral fraud following that year’s presidential election. The subsequent years saw Russia finance separatist movements in the two territories, with reports of the Kremlin covering the salaries and monetary expenses of police forces and civil servants in South Ossetia to avoid their defection into a pro-Georgian administration.

In 2015, Putin signed a Russian-Ossetian treaty of alliance with South Ossetian separatist leader Leonid Tibilov that included the full integration of Ossetian security institutions into Russia’s. Russia also agreed to increase salary and social benefits for South Ossetians to match those in Russia’s North Ossetia. The treaty was announced shortly after a similar deal was made between Russia and Abkhazia’s leader – a former KGB agent. It agreed to establish a new joint force of Russian and Abkhaz troops. Furthermore, Abkhazia would align foreign and defense policies with Moscow’s in exchange for subsidies to the Abkhaz Black Sea enclave.

In 2023, Moscow announced its plan to establish a permanent naval base in the coastal Abkhaz city of Ochamchire after Ukraine forced Russia to relocate its Black Sea Fleet from Crimea. According to Nikoloz Samkharadze, the head of Georgia’s Foreign Relations Committee (and member of the ruling Georgian Dream party), it will take approximately three years to complete the port. Samkharadze also stated, “We are concentrated on imminent threats and not on threats that might come in the future.” Analysts predict that Russian warships will strengthen Russia’s military presence in the Black Sea while granting it leverage over trade and transportation. Furthermore, the port will provide a harbor for Russia’s Black Sea fleet, which was forced to withdraw from its base in Crimea after several successful attacks by Ukraine.

Ochamchire has been used as a naval base for Moscow before, most notably as a key launching point for Russian advances into Georgia during the 2008 Russo-Georgian war.

Furthermore, Russia’s relationship with Ivanishvili, who served for a year as Georgian prime minister, has propelled the Georgian Dream party, which he leads, to dominance for more than a decade. Georgian Dream and Ivanishvili have made no secret of their antidemocratic and pro-Russian sympathies. Ivanishvili, Georgia’s richest man, made his wealth in Russia during the 1990s in the metals and banking industries, sectors known at that time for their questionable dealings. Years after returning to Georgia in 2003, Ivanishvili founded the Georgian Dream party, which eventually won the 2012 and 2013 elections.

Since then, the Georgian Dream party has served as the ruling party while quickly turning toward authoritarianism and the Kremlin. Much of this shift, which runs counter to the wishes of the majority of Georgia’s population, is credited to Ivanishvili, who has promised to strengthen relations with Russia. Since Russia’s 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Georgian Dream has ramped up its anti-Western messaging, reestablished direct flights between Georgia and Russia, and absurdly accused the West and specifically the United States of trying to drag Georgia into the Russia-Ukraine war.

Through Ivanishvili, Georgia’s judicial system has become subservient to the Georgian Dream party. After the party’s 2012 victory, Ivanishvili began to penetrate the courts by establishing relationships with Mikheil Chinchaladze and Levan Murusidze, influential judges who were able to cement their influence in the judiciary by granting immunity to colleagues. Cases of nepotism became normalized. The wife of a Georgian Dream party member of parliament, Vano Zardiashvili, was appointed as the head of the evaluation department of the High Council of Justice of Georgia, the oversight and regulating authority over the country’s judiciary.

The party’s control over the High Council of Justice has been further consolidated through several other appointments. Under Ivanishvili, Otar Partskhaladze was appointed as head of the Georgian judiciary. The decision to appoint Partskhaladze as prosecutor general was met with strong criticism from Georgian media and civil society, who were vocal about their concerns regarding his close relationship with Ivanishvili. Members of the Russian State Duma and Federation Council declared their support for Partskhaladze after hearing of the United States’ decision to sanction him. However, Partskhaladze was forced to forfeit his position after it was discovered that he had been convicted of a criminal offense in Germany.

Following Partskhaladze’s resignation, Irakli Shotadze, believed to be a close friend of Partskhaladze, assumed the position. Shotadze confirmed joining Ivanishvili’s meetings to settle business disputes. Shalva Tadumadze, Ivanishvili’s former lawyer, was also appointed as the head of the judiciary. Despite his lackluster credentials, Tadumadze became Georgia’s prosecutor general before receiving a lifetime judicial appointment.

It’s worth noting that many of these appointments were made through opaque processes, drawing criticism from Georgian civil society.

Under the captured judiciary, Georgia has passed several pro-Russian laws, such as the controversial foreign agent law, which requires organizations to register as “agents of foreign influence” if they receive more than 20% of their funding from overseas. The bill, which was praised by Moscow, has been criticized by Georgian opposition parties and civil society as well as Western governments.

Along with the judicial system, Georgia’s security services have also become a tool for the Georgian Dream party. Under the leadership of Grigol Liluashvili, a figure with a history of executive roles in Ivanishvili’s companies, the State Security Service of Georgia (SUSI) has been involved in a series of scandals. These incidents include spying on clergy members, political opponents, and civil society; organized attacks against Georgian media outlets and Georgian Dream Party critics; and orchestrating massive electoral fraud. In efforts to support Russian propaganda, SUSI accused Ukraine’s deputy chief of military counterintelligence of orchestrating a plan to overthrow the Georgian government. The operation, which was done in coordination with the Georgian State Security Service, claimed that Georgians fighting alongside Ukraine against Russia were part of the planned coup d’état.

In November 2024, shortly after the Georgian Dream party’s decision to suspend EU accession negotiations, Georgian security services deployed brutal force and allegedly tortured many of the hundreds of protestors they detained. There has been speculation, not yet confirmed, that Russian security personnel played a role in the brutal crackdown.

b. UKRAINE

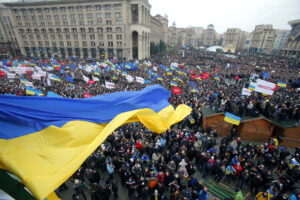

Russian corruption has been a cancer in Ukraine for decades, even factoring into the 2014 annexation of Crimea and 2022 full-scale invasion. Through support for pro-Kremlin politicians Viktor Medvedchuk and Viktor Yanukovych, backing of separatist regions, and targeting of Ukrainian security institutions, Russia has been able to weaken Ukrainian security and defenses. Following the 2014 Euromaidan protests, Moscow decided to move into Crimea and the Donbas. There, much as in Georgia, Russia deployed its strategy of supporting so-called separatist forces – even though there was little indigenous support for separatism from Ukraine in these regions.

Shortly after Putin’s 2000 presidential victory, Russia began interfering in Ukrainian affairs to discourage support for pro-Western politicians. Leading up to the 2004 Ukrainian presidential election, Gleb Pavlovsky, Putin’s then-presidential advisor, led a censorship and disinformation campaign to discredit pro-Western candidate Viktor Yushchenko and condemn his political party with support from the Social Democratic Party of Ukraine. In addition to Pavlovsky’s operation, direct Russian interference was discovered by electoral observers in connection with irregularities that awarded Viktor Yanukovych nearly 4 million suspicious votes and the election. The incident was a key factor in fueling the Orange Revolution, a 2004 political protest in Kyiv condemning electoral fraud that forced a rerun of the election and Yanukovych’s ultimate loss to Yushchenko.

After running again and winning the 2010 presidential election, attributable in part to Russian disinformation campaigns as well as discontent with the Yushchenko years between 2005 and 2010, Yanukovych immediately announced his intent to strengthen Ukraine’s relationship with Russia. Among other things, he removed pursuit of NATO membership from Ukraine’s foreign policy agenda. He also extended Russia’s Black Sea Fleet presence in Sevastopol until 2042, in exchange for a reduction in gas prices coming from Russia. Moscow’s naval presence in the Crimean Peninsula reflects a tactic within its use of strategic corruption in which Russia establishes parallel military, political, and judicial orders in overrun territories to diminish the influence of legitimate institutions. In doing so, occupied regions, such as the Donbas and Crimea, become laboratories of state capture that favor the Kremlin.

In 2013, Yanukovych proposed a Russian-Ukrainian action plan that awarded Ukraine a $15 billion loan, cheaper gas deliveries, and purchases of Ukrainian eurobonds. The agreement – revealed shortly after he announced that he was rejecting agreements with the EU – led to the Revolution of Dignity, a series of pro-democracy protests in Ukraine, which spurred Yanukovych to flee to Russia. Yanukovych cited Russian pressure as the driver behind his decision to reject the deal with the EU. In the wake of the Revolution of Dignity, Russia conducted its illegal annexation of Crimea with support from corrupt finances tied to Yanukovych.

Meanwhile, the Minsk agreements – ceasefire deals signed by Russia and Ukraine and witnessed by Germany and France in 2014 and 2015 to pause the conflict between Ukrainian forces and Russia-backed separatists in the Donbas region – were doomed to fail as Russia never abided by them. Their failure led eventually to Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022.

After the 2015 Minsk agreement, Moscow began to cover the salaries of local officials and separatist forces within the Donbas cities of Luhansk and Donetsk, with estimates suggesting it paid around $1 billion a year. Financial support for the separatist cities continued until 2021, when Russia announced plans to provide over $12 billion in financing over the span of three years. The funds were used to increase salaries to match those seen in the neighboring Russian region of Rostov. According to former Ukrainian minister Oleksiy Reznikov, Russia was spending $1.3 billion to maintain the occupation regimes in Donetsk and Luhansk.

During this timeframe, Russian-tied corruption within the separatist governments grew. The Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR) and Luhansk People’s Republic (LPR) maintained relationships with figures supporting Kremlin ideals in Ukraine. Oligarchs connected to the pro-Kremlin Party of Regions – which is also the party that endorsed Yanukovych’s 2010 presidential election – were behind much of the corruption seen in both separatist parties.

Part of the DPR’s responsibility was to ensure profits to militant groups across Donetsk, following guidance from the region’s principal oligarchs. Meanwhile, the LPR’s former leader, Ihor Plotnitsky, a former Soviet army officer and civil servant, was connected to cases of corruption involving Russian humanitarian aid and former local Luhansk leader of the Party of Regions, Oleksander Yefremov. Plotnitsky orchestrated the creation of the armed separatist group Zarya Battalion while also serving as its first commander.

Three days before the 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Putin formally recognized Donetsk and Luhansk as independent states, officially killing the Minsk agreements. The following day, Putin mobilized armed forces into the Donbas under what he called a special military operation. Both the DPR and LPR joined Russia’s official invasion two days later, intent on capturing the rest of the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts. At the time of this writing, Russia controls approximately 80% of the region with assistance from the DPR and LPR and 18% of Ukrainian territory overall.

Also linked to vast Russian corruption is Viktor Medvedchuk, the former people’s deputy of Ukraine and head of administration to Yanukovych. Medvedchuk, who chose Putin as the godfather to his daughter, was once one of the wealthiest men in Ukraine through his several businesses in the oil, metallurgy, and real estate industries based in Russia and Ukraine. His pro-Putin sympathies have led to several sanctions, including some related to his role as a financier for Russia’s annexation of Crimea. Most recently, Medvedchuk was found to have provided finances for Russia’s 2022 invasion, although the funds were likely embezzled before the plan began. He also has ties to the sanctioned pro-Russian media outlet Voice of Europe.

Relatedly, Ukrainian oligarch Dmytro Firtash made the most of his wealth in Ukraine’s gas industry. RosUkrEnergo (RUE) rose to prominence in 2004 and quickly became the intermediary in deals that sent Russian energy to Ukraine’s Naftogaz. At one point, RUE, owned equally by Gazprom and Firtash-owned Centragus Holding AG, held a monopoly for distributing gas into Ukraine. However, RUE was likely just a vehicle used by Moscow to siphon money from the operation and secure its influence over Ukrainian leadership. Using his ill-gotten wealth, Firtash financially propped up Yanukovych’s second presidential run and purchased a media outlet to send pro-Yanukovych messaging throughout the campaign.

Valeriy Khoroshkovskyi, a rumored business associate of Firtash, was nominated to key positions in Ukraine’s security sector, including deputy secretary of the National Security Defense Council, National Customs Service, and the head of the Security Service of Ukraine. These roles provided Khoroshkovskyi with opportunities to influence Ukrainian security institutions in favor of Yanukovych and Firtash, as evidenced by the 2009 investigation by the Security Service of Ukraine that attempted to seize gas linked to RUE. In his capacity as the head of the Customs Service, Khoroshkovskyi blocked the seizure of the Russian gas, saying it was an act done by “a criminal group that included the government leadership.”

Under Yanukovych, other pro-Russian officials like Oleg Tatarov were appointed to top security positions. Tatarov, who became the deputy head of the Main Investigation Department of the Ministry of Internal Affairs in 2011, was responsible for investigating crimes committed by law enforcement officers during the Revolution of Dignity. However, Tatarov’s tenure was stained with criticism and investigations on his alleged abuse of power.

Lastly, the response of democratic allies to the 2022 full-scale invasion has led to Russia’s creation of alternative opaque markets. Russia uses shell companies in these markets to access forbidden goods, participate in the global market, and undermine the effectiveness of international sanctions and export controls. Meanwhile, European dependency on Russian energy has forced certain carveouts that prevent restrictions from being the punitive tool they can potentially be, such as the Group of Seven oil price cap, which limits the market value of Russian oil to $60. At the time of this writing, the EU has gone a step a further to set a separate cap of $47.60. Even then, Russia has used its dark fleet to sell oil in the black market at prices above the cap. Russia also continues to prop up subsidiary banks and shell companies to access forbidden goods and finance its war in Ukraine.

4

POLICY RECCOMENDATIONS

The case studies in this paper show that Russian corruption is not a side effect of doing business with Moscow, but a deliberate tool of influence. To counter it, we recommend the following measures.

Europe must reconfigure trade and investment patterns to reduce strategic vulnerability, privileging allies over adversaries.

Business dealings involving Putin and his regime risk importing vulnerability and corruption into countries from Russia. Given the Kremlin’s state capture role in the Russian economy, it is impossible to do business there without some association with the regime, even in the event of a ceasefire or a lasting peace agreement with Ukraine. Business dealings with Russia also potentially subsidize, even indirectly, Russian aggression. Decoupling from the Russian economy would have as much if not more impact on Putin and the state than the series of sanctions imposed by the West. European governments should strengthen this strategy by adopting a new model of economics, in which countries establish trade relationships with military and democratic allies to protect supply chains from exploitation.

European countries should incorporate into their economic security strategy more financial transparency tools along with robust anti-money laundering mechanisms, such as foreign investment screenings, and enforcement mechanisms that target and prosecute Russian networks and intermediaries.

Russian investment in vulnerable sectors poses a significant threat to the EU. The bloc has recently introduced its first-ever comprehensive economic security strategy including an obligation for all member countries to develop a foreign direct investment screening mechanism. At the time of this writing, all EU members have completed legislation and mechanisms to screen foreign investment entering the bloc. However, the capacity for such systems to be effective remains negligible in Central, Eastern, and Southern Europe. The EU should prioritize administering a robust screening regimen throughout the entire region, along with enforcement protocols to complement other pro-transparency tools, such as beneficial ownership and anti-money laundering regulations.

Additionally, beneficial ownership databases should be openly accessible to stakeholders across Europe. This includes investigative journalists, law enforcement, financial institutions, and nongovernmental organizations. The same should be done for procurement transactions involving foreign entities and politically exposed persons on record attempting to access European financial institutions. The EU Authority for Anti-Money Laundering and Countering the Financing of Terrorism should lead these efforts.

Governments and/or publics in European countries should require companies that maintain Russian operations to disclose their rationale and risk assessment, raising the reputational and legal cost of engagement.

Companies still operating in Russia or dealing with Russian businesses should justify such willingness to do business with companies from a country guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity. With the current sanctions regime, firms who opt for economic gain rather than corporate responsibility, as declared in sanctions regimens across Europe, should be required to explain their approach. Doing so will increase the legal, operational, and reputational risk within their model, which ideally will discourage other companies from doing business with them. To be clear, not every company that still does business in Russia is corrupt or supportive of Moscow’s war against Ukraine, but the cloud of suspicion hangs over them, and the benefit of the doubt is not in their favor.

Europe and its democratic allies should prioritize secondary sanctions while considering lowering the 50% beneficial ownership rule.

Sanctions have become central to the international community’s strategy to attack Russia’s war chest. With an already comprehensive regimen, sanctioning countries should prioritize the escalation of secondary sanctions on targets that conduct and are willing to continue doing business with Moscow. The United Kingdom’s recent addition of powers that permit the use of secondary sanctions will allow the EU, U.K., and United States to act in unison to target enablers of Russian corruption.

Additionally, countries should begin the process of lowering the beneficial ownership threshold, which determines the level at which restrictions kick in for a company partly owned by a sanctioned individual. It currently applies to companies with stakes of 50% or more held by a sanctioned person. Individuals connected to the Kremlin can easily exploit this with returns that are still significant enough to benefit Moscow. A 25% threshold would bring EU practice in line with leading anti-money laundering standards and complicate efforts of pro-Kremlin businessmen from undermining Western sanctions. This should be part of the overall strategy of deconstructing the Kremlin’s state capture networks and safeguarding European consumers and businesses from future shocks related to reengagement with the Russian economy. This would encourage existing frameworks in the United States and U.K. to align in systematically targeting Russian enablers and intermediaries.

The European Union should support local and investigative journalism and civil society organizations that probe Russian corruption and behavior.

Investigative journalism continues to play a vital role in exposing Russian corruption and malign activity in Europe. That’s why Moscow has ramped up its censorship of independent media with harsh prison sentences and direct targeting of journalists and investigative organizations, even those outside of Russia. Despite Putin’s attack on Russia’s independent press, several organizations continue with their work, albeit beyond Russia’s borders, such as Meduza and Alexei Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation. Meanwhile, several others have been forced to shut down, as seen in the case of The Moscow Times’ VTimes, which closed after being designated as a “foreign agent” in 2021. Furthermore, many investigative watchdogs within Europe that have done valuable work detecting Russian influence and covert operations in the region can benefit from the support of the European Union.

Policymakers in the EU should prioritize supporting European journalists and organizations, as well as Russian outlets that have been forced out of the country and that conduct investigations on the Kremlin’s activities. The EU has existing mechanisms that can provide the necessary support through existing partnerships like the Ethical and Professional Media Environment for Central and Eastern Europe project, Investigative Journalism 4 EU fund, and the Sustainable Information initiative. The EU can help sculpt a more resilient journalism environment for Russian outlets. Doing so supports media freedom and pluralism, collaboration, and citizen engagement, all categories that the EU considers when providing support for the media sector.

About the authors

Albert Torres is a corruption and kleptocracy expert. He focuses on global issues that involve illicit financial practices and corruption in the public sector and most recently served as senior program manager of global policy at the George W. Bush Institute.

David J. Kramer serves as the executive director of the George W. Bush Institute and is a leading expert on Russia and Ukraine. He served eight years in the U.S. Department of State during the George W. Bush Administration, including as assistant secretary of state for democracy, human rights, and labor and deputy assistant secretary of state for European and Eurasian Affairs (responsible for Russia, Ukraine, Moldova and Belarus affairs as well as regional non-proliferation issues).

Ruslan Stefanov is the program director at the Center for the Study of Democracy (CSD), where he leads initiatives on economic security, anti-corruption, and geoeconomics across Europe and the Black Sea region. He is co-author of The Kremlin Playbook series and advises the EU and U.S. on countering state capture, sanctions evasion, and malign foreign influence.

Martin Vladimirov is director of the Geoeconomics and Energy Security Program at the Center for the Study of Democracy (CSD), focusing on the geopolitics of energy, sanctions enforcement, and Europe’s decoupling from Russian energy dependence. As co-author of The Kremlin Playbook series, his analysis shapes transatlantic policy responses to energy coercion, illicit financial flows, and hybrid economic threats.

About the George W. Bush Institute

The George W. Bush Institute is a solution-oriented nonpartisan policy organization focused on ensuring opportunity for all, strengthening democracy, and advancing free societies. Housed within the George W. Bush Presidential Center, the Bush Institute is rooted in compassionate conservative values and committed to creating positive, meaningful, and lasting change at home and abroad. We utilize our unique platform and convening power to advance solutions to national and global issues of the day. Learn more at bushcenter.org.

About the Center for the Study of Democracy

The Center for the Study of Democracy (CSD) is a European public policy institute dedicated to advancing democracy, freedom, and inclusive prosperity through evidence-based research, actionable policy solutions, and strategic dialogue. Founded in 1989 in Sofia, Bulgaria, CSD has grown to become one of the most influential think tanks in Europe, working to bridge the gap between analysis and policymaking in good governance, economic and energy security, the rule of law, information integrity, and social resilience. CSD is internationally recognized for its groundbreaking Kremlin Playbook series, which exposed the mechanisms of Russian economic influence and state capture across the globe. Learn more at csd.eu.