An earned pathway to citizenship, with restitution, allows the undocumented to fully assimilate and integrate into the United States without being unfair to those who have waited years for their green card applications to be approved. The solution must be in the rational middle ground between mass deportation and amnesty.

The undocumented immigrant population in the United States is a glaring sign of a broken immigration system. For too many years, immigration policy has been reformed at the margins, with executive orders filling in where legislation has been desperately needed.

Our immigration system is not built to accommodate the needs of our economy. Too few green cards are allocated to fill open jobs. Outdated provisions like per-country caps artificially limit the number of immigrants that may enter from any country every year. There are not enough pathways to entry for immigrants. The result is decades-long backlogs for many people who want to live and work in the United States legally but are instead frustrated by the very process enshrined in our laws.

This inadequate system created the undocumented population we have today. We cannot enforce and deport our way out of this. Congress should pass a top-to-bottom reform of our immigration system so that we can reduce the incentives for unauthorized immigration.

More than 10 million people in the United States don’t have a legal immigration status. Around a third of them are Dreamers — individuals brought to the United States by their parents as children. Most undocumented immigrants have lived in the United States for decades. Many have U.S.-citizen children. They fill an important role in our economy, representing around 4.6% of the labor force. These people are our friends, neighbors, relatives, and colleagues — it is in America’s interest to find a reasonable solution for this population. An earned pathway to citizenship, with restitution, allows them to fully assimilate and integrate into the United States without being unfair to those who have waited years for their green card applications to be approved.

The solution for the undocumented must be in the rational middle ground between mass deportation and amnesty. Congress’s continued failure to advance legislation tacitly endorses this unworkable status quo.

Characteristics of the undocumented in the United States

The undocumented population declined to 10.5 million in 2019 from 12.2 million in 2007. Nearly 60% of undocumented immigrants came to the United States legally and overstayed their temporary visas. This figure is up from 40% a few years ago and is part of a rising trend of unauthorized migration from Asian countries. While the popular narrative is that undocumented immigrants cross our border illegally and would be prevented by additional border enforcement, the data tell a different story.

The undocumented immigrant population in the United States is not driven by new arrivals. Long-term residency is the norm — about two-thirds of the undocumented have lived in the country for more than a decade.

Many undocumented immigrants live in mixed-status families. The Migration Policy Institute estimates that more than a fifth of unauthorized immigrants were married to U.S. citizens or green card holders. Over 4 million American-born children have at least one unauthorized immigrant parent.

Undocumented immigrants are crucial to the U.S. labor force. They fill important gaps, a fact that has become even more salient during the coronavirus pandemic. For example, American farmers rely on undocumented immigrants as agricultural laborers to harvest our food. In construction, 12% of the workforce is undocumented — these are the men and women rebuilding U.S. cities after devastating natural disasters. The undocumented clean our homes and workplaces and prepare the takeout we are eating so much of during the pandemic. They provide childcare; they tend to our lawns and gardens.

The undocumented are workers Americans interact with daily but do not fully see.

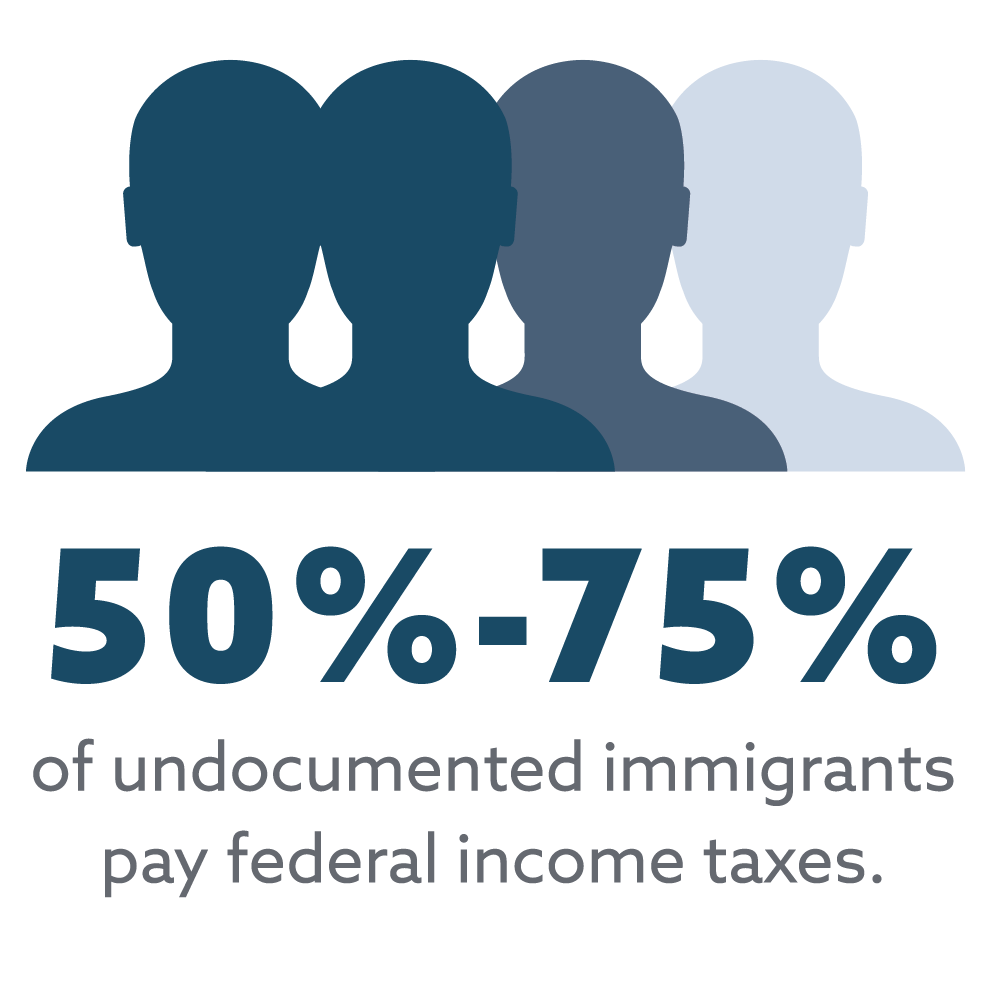

Undocumented immigrants pay billions of dollars in taxes every year. While they don’t have Social Security numbers or a legal work authorization, 50% to 75% pay federal income taxes. The undocumented also pay other taxes — sales taxes and property taxes, for example — just like other Americans who consume goods and services and live in houses or apartments.

The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy estimated $11.74 billion in state and local taxes were paid by undocumented immigrants in 2014. New American Economy estimated they contributed $100 billion in Social Security and $35 billion in Medicare funding from 2004 to 2014, bolstering the solvency of those programs.

Undocumented immigrants don’t qualify for most entitlement benefits, including SNAP food stamps and Social Security. They do not qualify for federal housing assistance. The only medical coverage they have is for emergency room visits, so they generally do not receive preventative care, unless it’s paid for by private insurance obtained through an employer. They pay into a social safety net that protects us, but they do not have a safety net for themselves.

Their lack of legal work authorization severely limits their ability to find jobs that meet their skills and education. Almost a fifth of unauthorized immigrants had four-year college degrees, a surprising statistic when considering the industries with high numbers of unauthorized workers, such as the service industry, hospitality, and construction. The Pew Research Center estimated that more than half of unauthorized workers were employed in those industries.

In many states, undocumented immigrants cannot obtain a driver’s license or an occupational license — even if they are highly skilled in that occupation.

The economic contributions of the undocumented are seen most clearly when we analyze what would be lost without them in the workforce. As the American Action Forum showed in its 2015 report on full enforcement of immigration law, real gross domestic product would decline by $1 trillion if we deported all the undocumented immigrants in the United States. A follow-up report in 2016 found full enforcement would annually decrease private sector economic output by 2.9% to 4.7%.

These immigrants do not choose to be here without legal authorization as if it is the easy way to migrate. They do it because they desire the same freedom and opportunity we have as Americans. But our immigration system does not have enough paths available which would allow them to legally migrate here.

Creating an earned path to citizenship for the undocumented

A legal immigration system that both meets the needs of America’s economy and is realistic about the challenges at the border would be a vital policy tool in preventing illegal immigration. Congress has the power to fix that by modernizing our immigration system to ensure that there are more legal channels for immigrants of all skill levels to come to the United States. But it does not address the challenge of what to do about the current population of undocumented immigrants.

Some legal tools already exist, such as sponsorship by family members who are already legal permanent residents or citizens of the United States. While some of the undocumented population qualifies for legal status based on family relationships, the wait times are many years, if not decades, long. Undocumented immigrants whose relatives are citizens have shorter wait times because of immigration law preference rules.

Some undocumented immigrants might also qualify for temporary worker visas, which would grant them legal status. But most of those visa categories do not offer a way for visa holders to adjust their status to legal permanent residence, so they are inadequate to the larger policy objective, which is integration and assimilation of this population.

These existing tools are inadequate to the task, however. Congress should pass an earned pathway to citizenship for the undocumented. Legislation like this will need these key components:

-

- Demonstrated continuous presence in the United States for a number of years;

-

- A background check so that the American people can be confident that any immigrant earning the right to stay in the United States has demonstrated the character of a good citizen; and

-

- Restitution, including paying any back taxes owed or showing proof of income taxes already paid, and paying a fee or penalty for the time spent here without authorization.

Both the George W. Bush Administration and the Barack Obama Administration supported legislation which contained these components. It’s not the intent of this paper to be proscriptive to Congress. Rather, the Bush Institute believes that these components are a good start to legislation that’s based on sound policy and is focused on workable solutions. Congress should use these components as building blocks for new proposals that meet today’s reality.

What will happen to the undocumented without legislative action? Many will continue to live and work in the United States at the jobs they can get, whether or not the positions are in line with their skills and education. Many will make less than similar legal workers because their employers know they can be exploited. They will continue to live with the fear of deportation. And they will continue to contribute to our country even though they can expect little in return.

In short, the status quo will remain. About 5% of our labor force will continue to contribute to our communities and pay taxes to support our safety net without any hope of becoming full participants in the country whose freedom and opportunity drew them.

Characteristics of Dreamers

Dreamers are undocumented immigrants who were brought to the United States as children by their parents. Some came illegally and others had parents who were on visas like the H-1B for highly skilled temporary workers. These children became Dreamers when they aged out of the immigration system on their 21st birthdays, while their parents remained stuck in long backlogs to adjust their temporary visas to green cards.

Dreamers received their nickname from the DREAM Act, bipartisan legislation originally filed in 2001. The DREAM Act, if it had passed, would have provided a special pathway to citizenship for these undocumented immigrants. The reasoning was simple: We do not hold children accountable for their parents’ actions.

The most defining characteristic of Dreamers is how American they are. Dreamers were raised in the United States as Americans, and they often know no other home than the United States.

Unsatisfied that the DREAM Act had not passed Congress, President Obama created Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) by executive action in 2012. The goal was straightforward: to protect Dreamers from deportation and give them the ability to work legally.

Among other requirements, applicants had to have arrived in the United States before their 16th birthdays; been continuously present in the United States since 2007; been in school, have a high school diploma or GED, or be honorably discharged from the military; and have no felony or significant misdemeanor convictions. An estimated 800,000 Dreamers have signed up for DACA since its inception. But with over 1 million DACA-eligible people in the United States, we know that there are more Dreamers still awaiting relief.

Without a permanent legislative solution for Dreamers, they will continue to live with the limited protection that DACA provides and the knowledge that any administration can use executive action to eliminate DACA protections and work permits. Deportation is a real possibility as long as Dreamers remain in this temporary status.

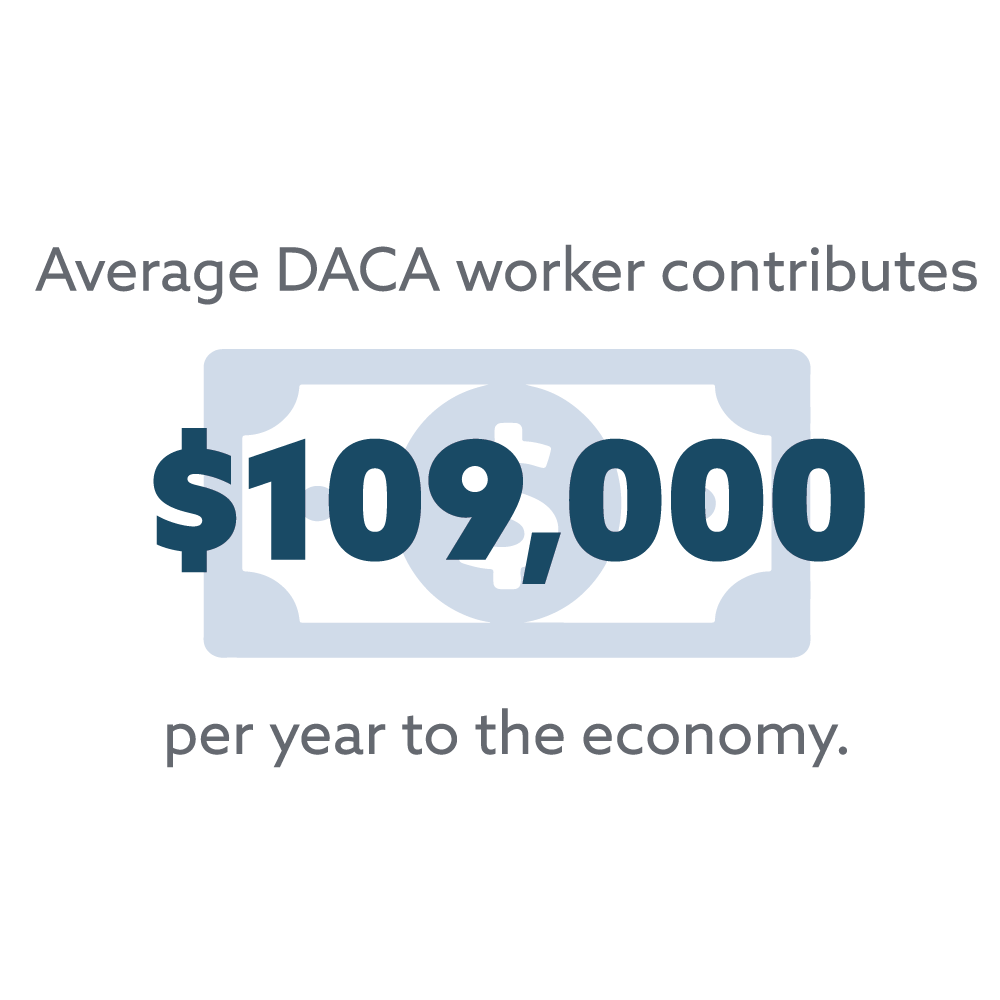

The United States misses out on the full contributions of Dreamers with each year that passes without a permanent legislative solution. DACA’s work permits demonstrate what Dreamers can do with a little bit of opportunity. According to an American Action Forum analysis, the average DACA worker contributes $109,000 per year to the economy. This is a number that will continue to increase each year as DACA recipients, who are often young and at the beginning of their careers, attain more education and work experience, increasing their earnings over time.

DACA recipients attend college in similar numbers to their native-born counterparts. More than half are employed; for those not currently working, 62% are enrolled in school. DACA recipients are more likely to work in jobs that meet their skills and education than Dreamers without DACA.

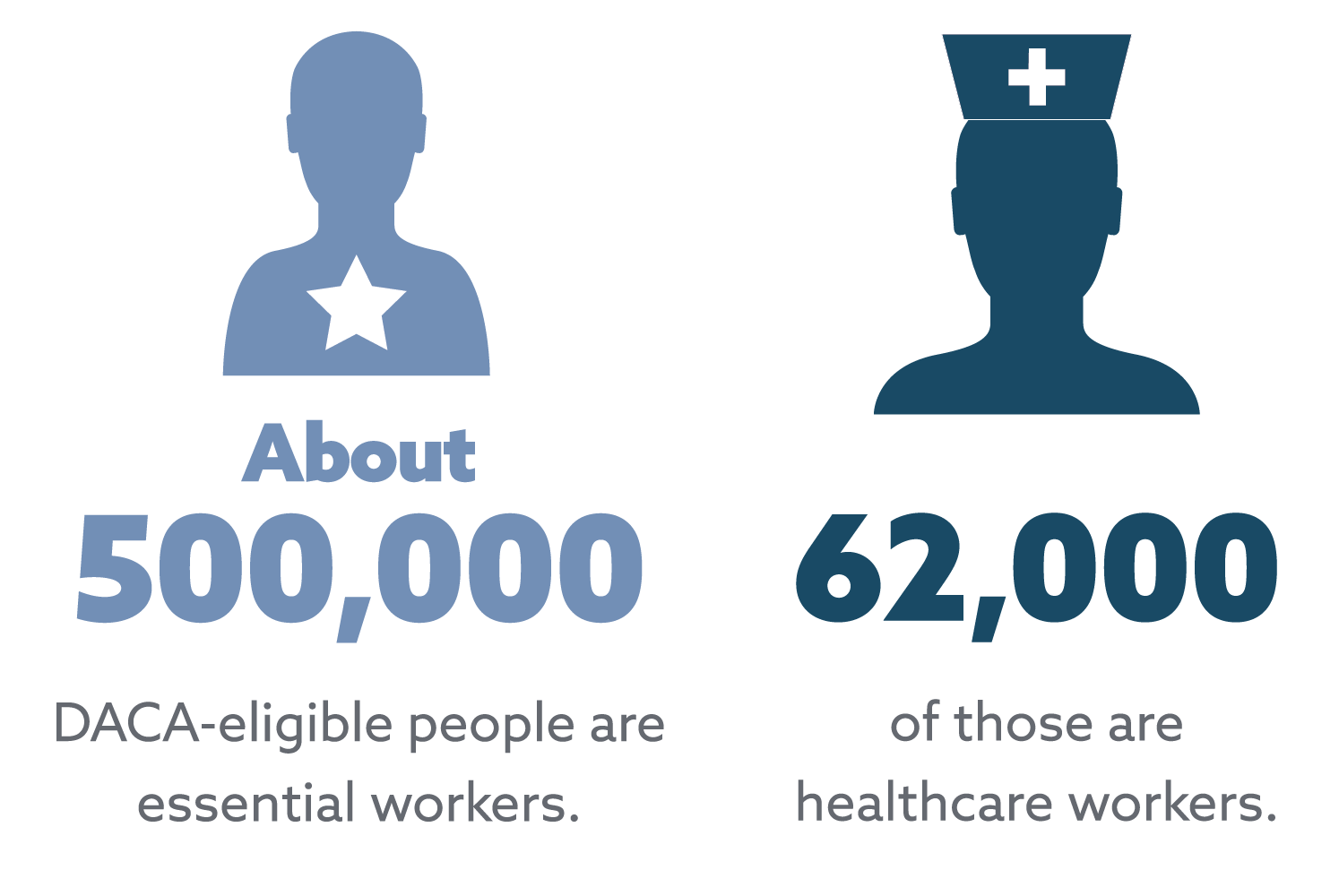

More important than their pure economic contributions are the role they currently play in our society. Many Dreamers are on the front lines of the COVID-19 pandemic. Nearly half of the over 1 million DACA-eligible people in the United States are essential workers, according to a New American Economy analysis of American Community Survey data. Among them are 62,000 essential healthcare workers. These are the people who are keeping us safe and healthy during these scary and uncertain times. They deserve a solution that recognizes that they are Americans, just like us.

DACA provides a strong legislative framework for Dreamers because it was based on the components of the many bipartisan versions of the Dream Act that have been filed in Congress over the last 20 years. Many of these bills have garnered dozens of co-sponsors and strong bipartisan support. Many members of Congress already are very familiar with the legislation..

Unlike other immigration reform proposals, a permanent legislative solution for Dreamers is not controversial. Polling conducted by the Pew Research Center in June 2020 showed almost 75% of Americans supported legislation to provide Dreamers with permanent legal status. Majority support for this cuts across nearly every demographic, with even most Republicans in favor.

Given the familiarity of the issue and strong bipartisan support, Congress should have already passed a permanent legislative solution for Dreamers. As it has not, it should be one of the first priorities the new Congress puts to a floor vote in 2021.

Why provide a pathway to citizenship

Providing a pathway to citizenship for the undocumented population, and a special pathway for Dreamers, is both practical and good policy. It’s unreasonable to deport millions of people who are working, contributing, and positively impacting our communities. It’s also expensive. A 2015 analysis by the American Action Forum found that fully enforcing current immigration law — detaining and deporting every undocumented immigrant in the United States and preventing any new unlawful immigration — would cost $400 billion to $600 billion, decrease GDP by almost $1 trillion, contract the economy by 6%, and take 20 years to accomplish.

In addition to the practical considerations, we must consider the larger policy implications of having millions of people who cannot, under our current laws, ever hope to be full participants in American civic life. It is a good thing to have all residents of a country as involved as possible. A democracy with more engaged participants can better reflect the will of its citizens. Active participation strengthens institutions, and a more engaged citizenry is better able to hold its democratically elected representatives to account.

Indeed, unlike legal permanent residents who choose not to become American citizens, and thus voluntarily limit their participation in American civic life, undocumented immigrants don’t have the choice. Further, given the restrictions of our immigration system, they never had an opportunity to apply for a green card and earn the chance to later apply for citizenship. It’s in our interest as Americans that these immigrants are integrated and assimilated fully into American life. We must find a legislative solution to integrate them. And we must redesign our immigration system to prevent another population of undocumented immigrants in the future.

The political argument on the undocumented too often devolves into respect for the rule of law versus respect for the dignity of the undocumented immigrants. This is a false choice.

The Bush Institute advocates a policy solution for the undocumented which embraces reality. It is not realistic to deport millions of workers. It is not realistic to assume that increasing security will reduce the undocumented population or prevent new migrants from coming. We must deal reasonably with the population we have, and we must redesign our immigration system to provide legal opportunities for migration, disincentivizing anyone from attempting to cross our border illegally or overstaying his or her visa.

Only Congress can provide a solution for the undocumented. And when it debates the fate of the undocumented, it should not forget it also has the power to design a new legal immigration system that will provide enough opportunities that no one has to live in the shadows.