The City of Dallas and the Dallas-Fort Worth metro area have lost much, though not all, of their affordability edge relative to other U.S. metro areas over the last decade. This trend reflects underbuilding throughout the United States coupled with fast-rising demand to live in North Texas that has strained the ability of developers to keep up.

The City of Dallas has a worse housing supply problem than Fort Worth or other surrounding cities. Dallas has seen extraordinarily low development of new income-restricted housing units in particular, relative to other cities. Home prices and rents have stopped rising over the last two years due to a surge in supply and slowing demand growth. However, if development slows in the DFW metro, prices and rents will likely start rising again before long.

If development does not accelerate in the City of Dallas, moreover, prices and rents will likely keep increasing relative to the rest of the region, with the likely consequence of further hollowing out of large parts of Dallas’s urban core.

The City of Dallas should build upon recent policy to:

- Accelerate development of new market-rate housing.

- Develop new policies to preserve existing “naturally occurring affordable housing” units and also federally subsidized developments that are approaching the end of their affordability period.

- Increase development of income-restricted units.

- Improve the collection and use of housing data to forecast local needs, set goals, and track progress over time.

Headline housing facts for Dallas, plus a projection:

- Dallas has lost much of its affordability edge over the last 15 years. Home price-to-income and rent-to-income ratios in both the City of Dallas and the DFW metro area are now just below the averages for metropolitan America as a whole and for core Sun Belt cities. Rents are in line with both averages. Home price-to-income ratios were some 20% to 40% below both averages in 2010, and rents were modestly below average, so Dallas has lost much of what was formerly a key competitive advantage.

- DFW versus Northeast/Pacific Coast metros: The DFW discount to coastal California metros is still much wider than one would expect based on a Bush Institute-SMU predictive model (described in the 2025 report “Build housing, expand opportunity: Lessons from America’s fastest growing cities”). Over the last decade, however, it has narrowed. Otherwise, DFW’s edge over major coastal metros has mostly disappeared. (Price-to-income ratios should vary based on differences across metros in incomes and amenities).

- DFW versus other large noncoastal metros: DFW’s price-to-income ratio is equal to or higher than all other noncoastal metros east of the 100th meridian, including metros throughout the Midwest and the Southeast. It’s priced as one would expect versus in-demand Mountain state metros (modestly cheaper), based on the Bush Institute-SMU predictive model.

- Home prices and rents are some 20% higher than they “should” be in a well-functioning market. City of Dallas home prices stand at about four to five times the household income of the families likely to live in them. Out of 16 neighboring cities, Dallas has the third lowest homeownership rate at 42%.

- Low-income renter households suffer most from high home prices and rents. Among all renter households in the City of Dallas, one out of every two is housing-cost burdened, meaning they spend more than 30% of their gross income on housing expenses. The average renter in Dallas spends 39% of their income on rent, but the lowest income renters – households with annual income below about $31,000 for a family of four – are stretched particularly thin, spending 78% of their income on rent. On these measures, Dallas performs in line with Sun Belt core cities on average, as all growing American cities face severe housing affordability challenges.

- Rent burdens prevent households from saving for a down payment or for other household needs and opportunities, in addition to the hardships they impose. Seniors, households with children, and Black and Hispanic/Latino renters are overrepresented in the population of cost-burdened renters. Single–parent households with children are most impacted: 75% are cost burdened.

- Rising DFW home prices and rents relative to incomes have primarily stemmed from underbuilding nationwide since 2000 and rapid growth in DFW-area housing demand between 2012 and 2023. The DFW metro has been more successful than average at adding both single-family homes and apartments, relative to what one would have expected based on the Bush Institute-SMU predictive model. But demand has grown faster than supply.

- The City of Dallas has a worse supply problem than the surrounding region. Price-to-income and rent-to-income ratios have increased more in the City of Dallas than in Fort Worth or large nearby suburbs even though housing demand has grown considerably more slowly than in other North Texas cities.

- For low-income renter households in the City of Dallas, there are just 28 affordable units for every 100 households with income at or below 30% of Dallas’s Area Median Income (AMI) and 60 affordable units for every 100 households at or below 50% of Dallas’s AMI, for a total gap of about 46,000 affordable units for all renters at or below 50% of AMI (that is, renter households with income below about $52,000 for a family of four).

- The City of Dallas has seen extraordinarily low growth in housing stock that is affordable to low-income renters since 2010. Attainable housing has two sources: (1) new development of subsidized, income-restricted housing units and (2) market-rate housing that becomes affordable “naturally” by depreciating in value over time relative to newer or better-maintained homes – a process called “filtering down” by housing scholars.

- Both mechanisms have performed poorly in Dallas over the last 15 years. There are 162,913 households in the City of Dallas with income at or below half of Dallas’s Area Median Income. Just over 70% of these households (115,332) rent their homes. Among renter households at or below 50% of AMI, nine in 10 (103,799) are cost-burdened, meaning they spend more than 30% of their gross income on rent and utilities. Although it’s difficult to determine what type of rental unit each household lives in, the high rate of housing-cost burden suggests that only a small share of households at this income level are living in income-restricted units or unsubsidized housing that is affordable to them.

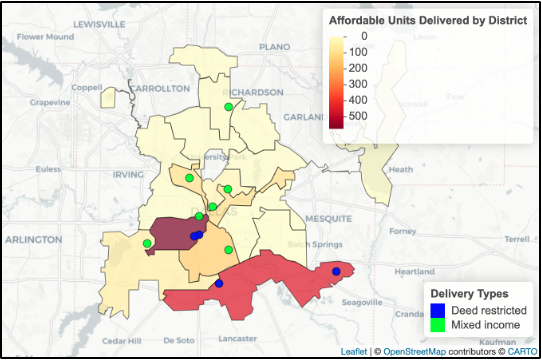

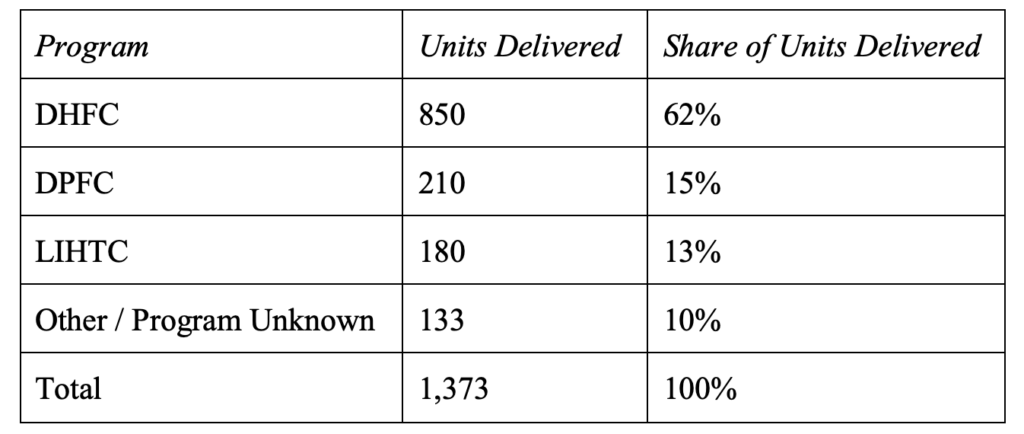

- Income-restricted housing units: The City of Dallas added some 400 units per year on average between 2017 and 2023 – fewer than in almost any other large U.S. city on a per capita basis. Development of income-restricted apartments fell more than 80% in the 2017-2023 period relative to 2010-2016. Development saw a partial recovery in 2024 due to a slate of new deliveries through the Dallas Housing Finance Corporation and Dallas Public Facilities Corporation, which accounted for an estimated 77% of new units. Meanwhile, some 400 to 1,000 older units built using the federal low-income housing tax credit (LIHTC) lose their 30-year rent-restricted status each year.

2024 Income-Restricted Deliveries, City of Dallas

-

- Naturally occurring affordable housing: The number of naturally occurring affordable housing (NOAH) units in Dallas (defined here as unsubsidized rental units affordable to households with income at or below 60% of AMI), is at about 117,000 units today and declining. Because NOAH units are not subsidized by government programs, they are vulnerable to rising property values and rents. For example, when new development is inadequate to keep up with demand, NOAH units may be sold, rehabbed, and occupied by more affluent renters or homeowners instead of lower-income renters.

- Supply helps. The City of Dallas has seen little change in home prices or rents since 2023. This reflects both a surge in new apartment supply in 2021 and 2022 – the DFW market has been one of the top two in the country for total apartment deliveries – and a softening of demand growth due to high mortgage rates since 2023. Relative to incomes, home prices and rents have fallen more than 5%. Austin, which has had an even larger apartment building boom adjusted for its population size, has seen prices fall almost 20% relative to incomes since their 2023 peak. However, even large supply increases in a single city don’t translate to big affordability improvements for the lowest-income families, since the elasticity of housing prices with respect to local supply is not sufficiently large, Bush Institute-SMU data and other studies show.

- A base-case projection: Suppose that over the next decade, foreign immigration into the DFW area runs at half its 2010-2020 rate, housing demand from people moving from elsewhere in the United States grows somewhat more slowly than its 2010-2020 rate because DFW’s housing price advantage over other places has narrowed, and birth rates remain at recent low levels. Then housing demand would grow at about the same pace that the DFW’s housing stock has increased since 2010: about 1.0% to 1.2% per year.

- If the region maintains the same development pace, we expect home prices and rents to grow more or less in line with incomes.

- If housing growth slows, however, home prices and rents will probably start rising again relative to incomes and the region’s competitive edge in home prices will weaken further.

- If the City of Dallas becomes more welcoming of new housing development than it has been, it might see home prices and rents stabilize relative to the rest of the region.

Possible steps forward for the City of Dallas:

Accelerate development of market-rate housing units:

- Ensure effective implementation of new Texas legislation (1) Senate Bill 15, which requires Dallas to allow developers to subdivide land parcels of five acres or more that have not been platted into lots as small as 3,000 square feet, allowing small homes and thin townhomes; and (2) SB 840, which requires Dallas to allow development of apartments or mixed-use real estate in commercially zoned areas (8% of Dallas land) and restricts the city’s ability to hold back office-to-residential conversions. Consider how to couple SB 840 with other local incentives to generate more affordable housing. Work with Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART) on its plans to promote transit-oriented development on DART-owned land parcels near transit stops, many of which are covered by SB 840. The city’s forwardDallas! Plan, approved in 2024, envisions adding some 15,000 housing units in the kinds of developments that have become possible under these measures.

- Zoning reform: (1) Revise the city’s zoning system to allow subdivision of raw land or rezoned commercial or industrial land into lots as small as 3,000 square feet under most circumstances. (2) Allow use of form-based code in more parts of the city. If Dallas were to reduce minimum lot sizes in the same way Houston has, it would add some 1,000 incremental units per year that would otherwise not be built, based on studies of Houston’s experience.

- Invest in downtown: Dallas can probably add at least 1,000 units per year over the next decade in its central business district if it keeps investing in improved quality of life and allows redevelopment of existing office properties

- Innovate: Loosen regulations that hold back wider deployment of manufactured homes, modular building technologies, tiny home communities, and other underused approaches.

We estimate that these measures together would likely add enough incremental units to support at least 4% to 5% incremental population growth over the next 10 years, we estimate.

Note: The City of Dallas has enacted several modest reform policies since 2019: the multifamily housing density bonus program (2019), a set of aspirational goals in the forwardDallas! plan (2024), and parking reform for certain locations (2025).

Preserve existing affordable units and maximize the long-term NOAH supply:

- LIHTC: Develop policies to extend affordability periods for LIHTC properties with approaching expiration dates.

- New landlords: Use the City’s subsidy tools to grow the pool of affordable and nonprofit developers/landlords prepared to keep units affordable to low-income families over the full life of existing properties.

- Strengthen neighborhoods: Expand the city’s minor home repair program. Develop a citywide NOAH preservation strategy, potentially including incentives for landlords to maintain quality and affordability of NOAH units.

Increase development of income-restricted housing units:

- Maximize the federal and state money on the table: Generate as many new units as possible from existing funding sources: the DHFC and DPFC, LIHTC, state grant programs, and the multifamily housing density program.

- Consider greater allocations to subsidized housing development in future bond issues. The City of Dallas has included much less funding for subsidized housing development in recent bond packages than several smaller cities including Austin and Charlotte.

- Activate publicly owned land: Hire an experienced private-sector real estate firm on retainer as a municipal property advisor charged with activating vacant land owned by the City of Dallas, Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART), and the Dallas Independent School District. The City of Dallas owns 2,800 parcels of vacant land. DART owns developable land adjacent to more than 40 transit stops.

- Activate vacant land owned by faith-based organizations. Across Dallas County, there are an estimated 2,200 vacant parcels of land (91M SF) owned by faith-based entities. 845 parcels are already zoned for residential use and could yield thousands of new units with modest density applied.

Use data to play offense:

- Project needs: Forecast future housing needs and backward plan instead of playing catch-up.

- Work with nonprofit entities to build a reliable data repository: Develop a rental housing data pipeline that aggregates all existing and anticipated sources of affordable housing and tracks affordability over time.

Note on sources: This summary draws on data and analysis contained in the report “Build homes, expand opportunity: lessons from America’s fastest growing cities,” released by the George W. Bush Institute-SMU Economic Growth Initiative in April 2025, and the Child Poverty Action Lab’s 2025 “Rental Housing Needs Assessment” (forthcoming publication). Underlying data in the two reports comes from the U.S. Census Bureau, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, and numerous private- and nonprofit-sector housing sources, including CoStar, Demographia, HR&A Advisors, the National Low-Income Housing Coalition, Yardi Matrix, and Zillow.

Cullum Clark is director of George W. Bush Institute-SMU Economic Growth Initiative

Ashley Flores is Chief of Housing at Child Poverty Action Lab