Review

The China that could have been

Two new books question whether Beijing and Washington were destined for conflict.

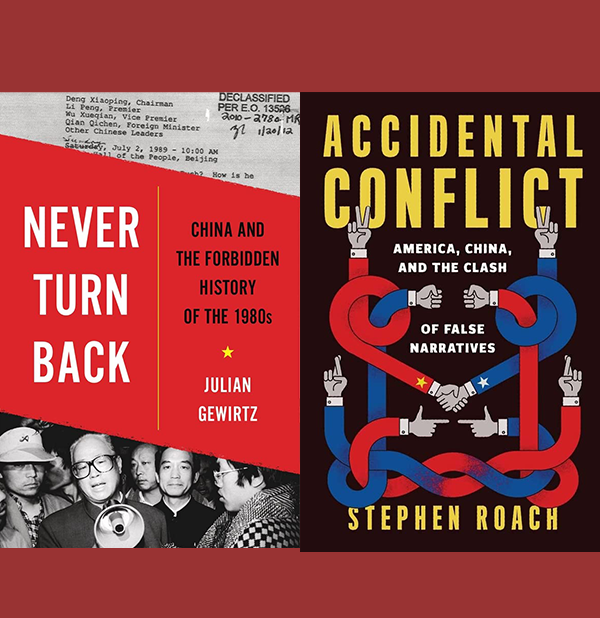

Julian Gewirtz, Never Turn Back: China and the Forbidden History of the 1980s. Belknap Press, October 2022, 432 pp.

Stephen Roach, Accidental Conflict: America, China, and the Clash of False Narratives. Yale University Press, November 2022, 448 pp.

For many Americans, the current hostility between the United States and China can be traced to one central cause: Beijing’s turn away from liberalization and toward policies that threaten vital U.S. interests and values. Under the increasingly autocratic leadership of President Xi Jinping, China has spent the last decade centralizing power, deploying unfair trade practices, threatening its neighbors, trying to undermine U.S. influence around the world, and engaging in an escalating series of provocations such as sending a surveillance balloon across U.S. territory earlier this year.

It’s no wonder that China-U.S. relations are now in “the foothills of a cold war,” as Henry Kissinger has put it. But did things have to turn out this way? Two new books offer valuable insights into why China has developed as it has – and why relations between the world’s two leading powers are spiraling downward at such a rapid pace.

The path not taken

Julian Gewirtz’s Never Turn Back: China and the Forbidden History of the 1980s is a meticulously researched account of the debates and power struggles that raged within the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) over the country’s direction in the years following Mao Zedong’s death in 1976 – a process that culminated in the bloody massacre of protesters in Tiananmen Square in 1989. Gewirtz, a scholar and the author of two previous books on China who is currently serving on the National Security Council, depicts this period as a pivotal decade that could have set China on a different course but for several twists of fate.

Throughout the 1980s, Gewirtz shows, China’s leaders fought a continuous bureaucratic battle over whether to push for more reform or to deepen the party’s monopoly on power and control. During the first four years after Mao’s death, the CCP dramatically reshaped itself: rehabilitating Deng Xiaoping and other senior leaders purged during the Cultural Revolution, using show trials to rid itself of senior Mao loyalists such as Jiang Qing (Mao’s widow), and elevating Deng’s allies – most notably Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang – to top positions. (Hu became CCP general secretary in 1981, and Zhao became premier in 1980.) Zhao, in particular, would go on to play a critical role, using his rehabilitation to make himself the chief architect of China’s transformational economic reforms. On his watch, the country doubled its real GDP per capita and reduced extreme poverty by more than 60%.

At the same time, however – and here Gewirtz’s history differs from conventional accounts of this period – the CCP recommitted itself to Leninist party dictatorship and insisted on the primacy of Marxist ideology and central planning. Under Deng’s leadership, the party ruthlessly squashed every outbreak of dissent, such as the 1978 Democracy Wall movement and campaigns against “spiritual pollution” in the mid-1980s. The CCP tolerated no public dissent. In 1987, Deng forced out Hu for permitting too much open discussion of reformist ideas that conflicted with party orthodoxy. Not even Zhao was safe: Despite the success of his economic reforms, he alienated Deng and other party elders in 1988 by proposing a modest political opening – limited elections for low-level regional posts with only CCP members permitted to run – and by introducing a botched price reform that sparked a bout of galloping inflation. When Zhao began to argue for a nonviolent end to the Tiananmen protests, which were sparked by Hu’s death in April 1989, Deng had him arrested and ordered the crackdown of June 3-4.

China’s remarkably innovative economic reforms were always destined to clash with the CCP’s ferocious commitment to maintaining power.

From today’s perspective, the most significant section of Gewirtz’s book is his description of how the CCP sanitized its official history of the 1980s after Tiananmen. After the massacre, the party closed ranks and worked to erase all records of its recent internal disagreements. In the process, Beijing also virtually airbrushed Zhao out of history, allowing only a three-line notice on page four of the People’s Daily when he died under house arrest in 2005. Worried that a divided leadership might threaten its control, the CCP also exaggerated the level of Deng’s involvement in China’s economic reforms – reforms in which he had actually played only a supporting role. Deng, for his part, sought to balance economic opening with reinforced political control, making it somewhat ironic that President Xi, decades later, would choose to largely airbrush Deng out of the picture. But President Xi’s move is not so surprising: His CCP cannot tolerate the presence of more than one paramount leader in its hagiography.

Gewirtz’s book raises the question of whether there was ever much chance that communist China could develop in a more democratic direction. The author suggests that, but for a series of bad breaks – the poor rollout of Zhao’s price initiative, Hu’s unexpected death, and even Deng’s tinnitus, which prevented him from hearing Zhao during a crucial May 1989 meeting – Zhao might have succeeded in pushing through political reforms. But Gewirtz doesn’t actually prove this point. A close reading of Never Turn Back actually suggests the opposite: that China’s remarkably innovative economic reforms were always destined to clash with the CCP’s ferocious commitment to maintaining power, and the latter priority was nearly certain to prevail.

Mixed (and missed) messages

In Accidental Conflict: America, China, and the Clash of False Narratives, Stephen Roach takes on the question of whether it’s possible to reverse the worsening course of U.S.-China relations today. Roach, a longtime Asia hand at Morgan Stanley who now teaches at Yale, argues that the emerging cold war is a product of “misplaced fears” and, as his title suggests, “false narratives.” In particular, he contends that U.S. trade officials routinely exaggerate China’s misbehavior in areas such as intellectual property theft and unfairly criticize Beijing for legitimate initiatives to promote homegrown innovation. In Roach’s view, the primary cause of Washington’s hostility is the U.S. bilateral trade deficit with China, which serves as a painful marker of U.S. decline for many American leaders. As for the cause of the trade imbalance itself, Roach points to inadequate savings rates in the United States and excessive savings rates in China.

So the country needs to put its own house in order by increasing its support for science, education, and infrastructure building, and through fiscal reforms to stabilize its national debt.

The author warns that China and the United States are drifting toward what the Harvard scholar Graham Allison has called a “Thucydides trap”: a conflict between a rising power and an established one, typified by ancient Sparta’s fear of a rising Athens and the resulting Peloponnesian War. This is hardly an original observation, but in Accidental Conflict, Roach offers a number of useful suggestions for how to ease tensions. Addressing America’s trade deficit through bilateral agreements is certain to fail, he argues, so long as the United States keeps investing more than it saves. So the country needs to put its own house in order by increasing its support for science, education, and infrastructure building, and through fiscal reforms to stabilize its national debt. Roach also thinks Washington should try to rebuild trust with Beijing by striking intellectual property agreements and other measures that would help address Americans’ grievances.

The book’s emphasis on trade imbalances as the main root of U.S.-Chinese antipathy, however, is less convincing. Roach himself seems conflicted on whether the trade deficit actually matters (other than as a source of false narratives). And he doesn’t convince the reader that eliminating the trade imbalance would alter the main contours of U.S.-China relations. Indeed, economically decoupling the two countries, as both governments now seem intent on doing, might both reduce trade imbalances and increase the odds of military conflict.

Most fundamentally, Accidental Conflict sidesteps the problem that certain key narratives may, in fact, be true. President Xi, for example, really does proclaim aspirations for territorial expansion that could provoke a showdown with U.S. allies or the United States itself; there’s nothing false about that story. Roach also pays scant attention to the South China Sea and to President Xi’s Belt and Road Initiative, and he all but ignores China’s threats against Taiwan. He does acknowledge that Russia’s Ukraine invasion poses “grave risks to world peace” and that China’s support for Russian President Vladimir Putin has put President Xi in a tricky spot, but he never extends the analogy to China and admit that it, too, may present risks.

Roach expresses hope that China and America will increase their cooperation on climate, cybercrime, and COVID-19. But he leaves out that China is the world’s largest carbon emitter and a leading source of hacking, and he dismisses the Wuhan lab leak theory – the suspicion that the coronavirus emerged from a Chinese testing facility – even though the FBI and the Department of Energy recently concluded it may be true.

Roach is also less than clear in identifying China’s false narratives about the United States. President Xi’s claim that the United States aims to contain China’s expansion seems to be true, based on President Joe Biden’s statements on how he would respond to an invasion of Taiwan. But President Xi’s assertion that the United States is working to undermine China’s economic growth is far less plausible and seems more like a pretext for fueling public distrust for the world’s sole superpower.

One possibility Roach doesn’t consider: that China’s economic growth, which has been slowing dramatically in recent years, may soon stagnate – thanks to the country’s shrinking population and abandonment of economic reform. If President Xi comes to think his best opportunity to conquer Taiwan and take other territory is coming soon but could then diminish, he may be tempted to roll the dice sooner rather than later. Should that happen, U.S. policymakers will face the most dangerous period in the history of U.S.-China relations.

Indeed, for Washington, these two books point to some uncomfortable realities. The CCP is unlikely to pursue any reform that weakens its monopoly on power, and its leaders have strong incentives to keep spreading the narrative that the United States is blocking legitimate efforts to improve the Chinese people’s well-being. Roach is surely right that the United States should pursue formal agreements on contentious economic issues where possible, sustain the mutually beneficial trading relationship – in products that don’t affect national security – and invest in U.S. competitiveness by putting its own house in order. But keeping peace with China may also require a more explicit articulation of U.S. vital interests and values and a commitment to matching words with hard power.