Review

Beijing’s war on history

The Cultural Revolution still shapes China today – even as the government tries to erase its memory.

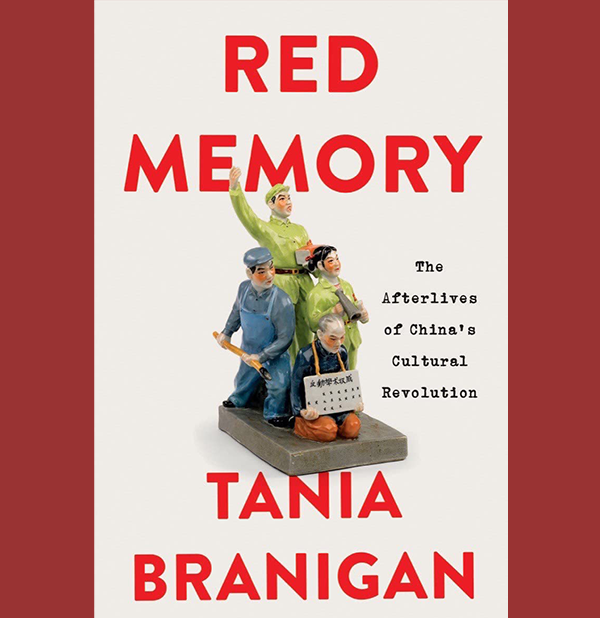

Tania Branigan, Red Memory: The Afterlives of the Cultural Revolution. W. W. Norton & Company, May 2023, 304 pp.

On Feb. 6, 2012, Wang Lijun, the police chief of Chongqing – a major metropolis in southwest China – drove to the U.S. consulate in the nearby city of Chengdu. Once there, according to then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, Wang asked for political asylum and then spent the night inside the building. The next day, his boss, Bo Xilai – then Chongqing’s powerful Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Secretary, as well as a rising star widely seen as a future leader of the country – arrived on the scene, was admitted into the consulate, and persuaded Wang to leave with him. After exiting with Bo, Wang disappeared; the Chongqing government claimed he had been suffering from stress and was receiving “holiday-style medical treatment.”

The incident shook U.S.-China relations and had a profound effect on Chinese politics. The following month, the powers that be in Beijing relieved Bo of his post and later charged him with corruption and the abuse of power. They charged his wife, Gu Kailai, as an accomplice in the murder of a British businessman. As of today, Wang is serving a 15-year prison sentence for abuse of power, defection, bribe-taking, and “bending the law for selfish ends.” Bo and Gu have been even less fortunate: both are in prison for life. Bo’s rapid rise and fall, the severity of his punishment, and his privileged status – a status that ultimately could not save him or his family – were all strongly reminiscent of an earlier tragic experience that would come to fundamentally shape China’s society and politics.

Understanding President Xi is critical to understanding the likely trajectory of China in the coming years, as well as its relationship with the United States.

On Nov. 15, 2012, Xi Jinping, a longtime associate and rival of Bo’s, was sworn in as the CCP’s next general secretary, a post he will likely retain until his death – as did Mao Zedong, the founder of the People’s Republic. Understanding President Xi is therefore critical to understanding the likely trajectory of China in the coming years, as well as its relationship with the United States. But as Tania Branigan, a former China correspondent for The Guardian, argues in Red Memory, you can’t hope to understand President Xi – or the country he rules, or the Bo story – without first understanding the Cultural Revolution, which ran from 1966 until Mao’s death in 1976.

During the first years of the revolution, roving bands of Red Guards – radical militias made up mostly of teenagers – prowled the streets of China’s cities looking for “counterrevolutionaries” guilty of “subversive behavior.” With Mao’s explicit blessing – the Chinese leader saw the chaos as a way to root out internal enemies – they publicly denigrated, tortured, and murdered anyone they deemed insufficiently committed to the communist cause. Rival Red Guard factions, divided not by ideology but the scale of their brutality, ultimately turned on one another, fighting with guns and even tanks, all with the tacit approval of the military and the police. By the time the bloodbath ended, somewhere between 500,000 and 2 million people had been killed (the figure is vague because record-keeping was sparse). The thesis of Branigan’s incisive and informative new book is that the violence and dislocations committed then continue to reverberate today, shaping the thinking of China’s leaders and citizens alike. Coming to grips with what happened during that period is thus critical to understanding what is likely to come in the years ahead.

Bian Zhongyun (WikiCommons)

Bian Zhongyun (WikiCommons)

Descent into darkness

The Cultural Revolution began in earnest on Aug. 5, 1966, with the murder of Bian Zhongyun, or “Teacher Bian” – a beloved deputy principal at an elite high school attached to Beijing Normal University. Accusing her of acting as a “counterrevolutionary,” female students, some in their early teens, “dragged her onto a stage in shackles and forced her to kneel while they kicked and struck her, beating her with iron-banded wooden rifles.” The abuse continued until Bian lay “covered in blood and dirt, with traces of foam at her mouth.” Though the nearest hospital was just across the street, she was left outside in the suffocating heat for hours, until she died from her wounds. As for the students who had attacked her, they eventually got bored and went to buy ice pops.

Unable to prevent his wife’s murder, Bian’s husband, Wang Jingyao, instead meticulously documented its aftermath, including taking a photo of their four young children “lined up by size, Von Trapp style, behind the battered body of the woman who once fed and soothed them.” Wang would keep these gory mementos, along with his wife’s ashes, hidden for most of his life, awaiting justice. But that justice never came. Reminiscent of Hannah Arendt’s study of the banality of evil in Eichmann in Jerusalem, Branigan struggles to comprehend not just the scale of the horrific cruelty perpetrated on Bian and the Red Guards’ many other victims but also the senselessness, the casualness, and the randomness of it all – as well as the fact that it was children who, Lord of the Flies-style, became the manifestation of that evil.

As Branigan recounts, 13 days after Bian’s murder, at a massive public demonstration in Tiananmen Square, a 17-year-old girl named Song Binbin pinned a red armband on Mao – thereby publicly affirming his approval for the unfolding carnage. As Branigan notes, Song wasn’t just any Red Guard; she attended Bian’s school and would become the guards’ student leader. In the years after Mao’s death, she went on to live a life of privilege. After getting her doctorate in the United States, she eventually became a U.S. citizen and worked for the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection for 15 years before moving back to China in 2003.

The thesis of Branigan’s book is that the violence and dislocations committed during the Cultural Revolution continue to reverberate today, shaping the thinking of China’s leaders and citizens alike.

Song was what Chinese call a “princeling” – a child of one of the founders of the People’s Republic. Being a princeling is as close to royalty as one can get in modern China. But few other princelings got through the Cultural Revolution as well as she did. The children of Liu Shaoqi, then the country’s President, and of Deng Xiaoping, then Vice Premier, also became Red Guards. But Bo and Xi were far less lucky. Then in their teens, the two boys’ special status made them targets. Xi, who was 15 years old at the time, was denounced by his own mother, and his half-sister committed suicide after their home was ransacked by the Red Guards. Xi’s once-powerful father, Xi Zhongxun, was imprisoned (as was Liu), and the young Xi was exiled to a desolate village in northwest China, where he spent the next seven years doing hard physical labor. Branigan’s book recounts in detail the misery of Xi’s experience – a far cry from the rustic, character-building getaway that current Chinese propaganda on the period depicts. Yet the Cultural Revolution did profoundly shape the young princeling, who said he couldn’t “stand to be bullied.” According to contemporaries, those years left young Xi with a heightened sense of “threat and insecurity” that would last for the rest of his life and “manifest in his policies once he achieved ultimate power” – policies that would include expanded censorship, tighter controls on the economy, and the brutal internment camps he’s created in the majority-Muslim region of Xinjiang.

The sentencing of Chinese politician Bo Xilai on September 22, 2013 in Beijing, China. (Photo by Feng Li/Getty Images)

The sentencing of Chinese politician Bo Xilai on September 22, 2013 in Beijing, China. (Photo by Feng Li/Getty Images)

Important as the Cultural Revolution was in shaping China’s future leader, Branigan spends most of the book focused on the Red Guards themselves. In multiple interviews, she cajoles former members to tell her why they did what they did and whether they feel guilty about it. But she gets few satisfying answers beyond descriptions of their slavish devotion to Mao and of the revolutionary spirit of the times. Although Song eventually publicly apologized for the role she played “in failing to protect the leaders of the school,” she never admitted her responsibility for participating in Bian’s murder. Indeed, none of Branigan’s subjects seem contrite or compassionate toward their former victims. A few have sought to make amends by building makeshift remembrance sites, and some have written blogs about their experiences or joined social clubs where they and other former guards hold frank discussions about what they did. But nearly everyone Branigan interviewed insists that, rather than harp on the past, China should move on and build a better future for their children and grandchildren. Of course, they mostly fail to note the irony that the future being constructed is far more capitalist, and far less egalitarian, than the one they purportedly fought for during the late 1960s and early 1970s.

A traumatized nation

Returning to President Xi toward the end of the book, Branigan draws a direct corollary between his consolidation of power since taking office in 2012 and the simultaneous closing of the (already small) aperture that existed to discuss and draw conclusions from the crimes of the Cultural Revolution.

In the years following Mao’s death, the madness of the preceding decade taught China’s leaders – particularly Deng, Mao’s successor – the importance of setting age and term limits for government officials, as well as the strict turnover of party leaders within this system, to prevent ossification and consolidation of power. These and Deng’s other managerial reforms, most notably institutionalizing a meritocracy that prioritized good performance and encouraged candid assessments of shortcomings, worked well, contributing to China’s spectacular economic growth – at least until President Xi took office and began systematically ripping the playbook to shreds. The anti-corruption purges President Xi has since used to take down Bo and countless other officials have ostensibly been aimed at curbing the massive graft that runs rampant in China’s government. (Branigan recounts an episode in which, after one high-ranking military official was busted, it took a dozen trucks to haul away his ill-gotten loot, which included a golden statue of Mao.) All along, however, President Xi’s real goal – just like Mao’s during the Cultural Revolution – has been to take down his political opponents. Nothing made that clearer than the most recent National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, in October, when President Xi had his frail-looking predecessor, Hu Jintao, ushered from the auditorium.

Where the Chinese Communist Party once tolerated an (admittedly) small bit of pluralism, at least among its leaders, today only rigid Leninist ideology and unyielding loyalty to President Xi are permitted.

Propaganda poster depicting Mao Zedong, above a group of soldiers from the People's Liberation Army. (IISH Stefan R. Landsberger Collection via WikiCommons)

Propaganda poster depicting Mao Zedong, above a group of soldiers from the People's Liberation Army. (IISH Stefan R. Landsberger Collection via WikiCommons)

Having successfully cleared the field, only two men matter in President Xi’s China: the former princeling and the ever-ubiquitous Mao. Deng’s famous advice to “hide our strength and bide our time,” which did so much to enable China’s success during the three decades after Mao’s death, has been abandoned. President Xi’s grand project, known as the “rejuvenation of the Chinese nation,” includes avoiding what he calls “historical nihilism” – a term that encompasses any open discussion of the Cultural Revolution or of other mistakes made by Chinese leaders. Deng, who took a relaxed view of orthodoxy – a flexibility that enabled his China to boom – famously said that it did not matter whether a cat was black or white, so long as it caught mice. For President Xi, however, only a red cat will do, regardless of what it does or doesn’t catch. Where the Chinese Communist Party once tolerated an (admittedly) small bit of pluralism, at least among its leaders, today only rigid Leninist ideology and unyielding loyalty to President Xi are permitted. As the outspoken billionaire Jack Ma has learned, even titans of industry who were previously considered untouchable can now be punished for straying from the party line. (In 2021, Ma mysteriously disappeared for three months after publicly criticizing China’s draconian “zero-COVID” policies.)

While many American leaders, including President Joe Biden and key members of Congress, are now rightly focused on the significant long-term threat China poses to U.S. global primacy in the security, economic, and technological realms, they often miss the ideological underpinnings of Beijing’s policies and of its leaders, as well as the effect of the history Branigan’s book so thoroughly examines. Even after the violent 1989 crackdown on student protests in Tiananmen Square, many U.S. leaders continued to maintain that China’s economic opening would bring with it political liberalization, as well. Rather than the end of history, however, China’s embrace of capitalism has led to an ideological hardening, which has forced the United States to scramble to assemble a new strategy in response. Congress’ new Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party is the most recent example of this process, and it surely won’t be the last.

Toward the end of her book, Branigan offers a glimmer of hope that China could still change for the better. She quotes the Chinese political activist Xu Youyu, who told her that “during the Cultural Revolution, Mao Zedong was one brain controlling 800 million Chinese people,” whereas today, “at least half” of the population “have their own minds.” In her conversation with Xu, Branigan even concludes that “there are faint murmurings of discontent,” at least in private. The unfortunate fact, however, is that Xu lives in exile and represents a small and severely oppressed group of dissidents willing to openly speak such thoughts. Still, the hope for a more liberal China, and improved U.S.-China relations, lies in the empowerment of voices such as his – of people who lived through the Cultural Revolution and drew from it vastly different conclusions than has President Xi. Unfortunately, we all may have to wait a very long time before that comes to pass.