Point/Counterpoint

Do America’s institutions still work?

Debates over the state of U.S. democracy eventually lead to the question of whether our government structures still function as intended. So we asked experts from both sides of the argument to weigh in.

A 1787 copy of the U.S. Constitution on exhibit at the George W. Bush Presidential Center.

A 1787 copy of the U.S. Constitution on exhibit at the George W. Bush Presidential Center.

The U.S. Constitution established the Electoral College for several reasons, including to ensure fair representation to all Americans no matter where they live. Does it still accomplish that goal?

POINT

THE CONSENSUS CONSTITUTION

America’s charter may date from another era. But its design still serves the broad public good, and changing it could cause more problems than it solves.

by Jay Cost

The U.S. Constitution is a very old instrument of government. Having recently celebrated its 236th birthday, it is now the longest-running document of its kind still in effect today.

But is that a good thing or a bad thing? In recent years, an increasing number of critics have begun pointing to the Constitution as a source of America’s worsening political dysfunction. The document, they argue, fails to reflect contemporary democratic values. When the United States was originally founded, the franchise was much more restricted, and few offices were open to public election. But times have changed, the argument goes, and the Constitution’s antidemocratic institutions need to be done away with so that the people can truly rule themselves.

Many such critics point to the Electoral College, which was originally designed with an expressly antidemocratic function: Rather than the people choosing the president, state governments chose electors, who then got to choose whichever president they preferred. In the early 1800s, states altered the way electors were chosen, and today, all 50 states use the popular vote for president, with electors pledged to their state’s winner. That makes the presidency a democratically elected position in a meaningful sense.

But critics still take issue with how electors are apportioned. Every state gets a number equal to the size of its House and Senate delegations combined, for a minimum of three (since six states – Alaska, Delaware, South Dakota, North Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming – have only one House member each). Critics charge that this setup excessively favors small states. Compounding the problem, most states allocate their electors on a winner-take-all basis, meaning that if a presidential candidate wins a state by just a single vote, he or she gets all that state’s electors. Together, these features allow the election of minority presidents: candidates who did not win the popular vote but nonetheless carried the most electors. Highlighting these facts, some critics conclude that the Electoral College should be abolished and the president should be directly elected.

At first blush, such arguments seem sensible. To many of us in the West, where democracy has long since established itself as the dominant or hegemonic ideology of governance, antidemocratic institutions like the Electoral College look patently unfair. The people, and the people alone, should rule, and antidemocratic institutions should be done away. As Thomas Jefferson argues in the Declaration of Independence, governments are legitimate only insofar as they derive “their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

But getting rid of the Electoral College would be a dangerous mistake.

Congress tallies Electoral College votes on Jan. 8, 2009. (Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

Congress tallies Electoral College votes on Jan. 8, 2009. (Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

The power of consensus

To appreciate the ongoing value of the Electoral College, remember that, even if we agree with Jefferson that democracy is the only legitimate form of government, unrestrained democracy can still be dangerous. Democracy, after all, is merely a process. It is how policy is formulated – in this case, by the masses. Democracy doesn’t answer the other basic question about policy: whom should it benefit? Should policies be designed to secure the welfare of the whole community or merely the numerical majority that happens to control the mechanisms of the state? Like any form of government, a democracy can turn tyrannical, even if it is a tyranny of the majority – because, like all other forms of government, democracies are ruled by human beings, who have a strong tendency to use their powers for their own good or enrichment.

This danger – that all just governments risk descending into tyranny – has preoccupied political philosophers for millennia. Plato and Aristotle both tackled it, and in his Politics, the latter suggested that the best practical solution might be blending democracy with plutocracy, or the rule of the rich. That way, the two forces could keep each other honest. Many centuries later, England emerged from the Middle Ages with a mixed system that blended the rule of the one (the king) with the rule of the few (the House of Lords) and the many (the Commons, although even this body was originally limited to property owners). The idea, once again, was that the vices of one would check the vices of the others.

When the Founding Fathers set about creating the American system of government in 1776, however, reproducing that blend was not an option available to them. The king of England had never bothered to create an aristocratic class in his North American colonies. Besides, the main distinguisher of nobility in Europe – land ownership – was virtually pointless in the New World, where land was so cheap. So there could be no American House of Lords to prevent tyranny of the majority, and the idea of recreating the monarchy was a nonstarter. The founders had to find another way to make democracy behave itself, without the benefit of the traditional checks.

The framers believed that the larger, broader, and more considered a majority is in support of an initiative, the greater the odds are that that initiative will promote the general welfare.

The alternative they came up with was the doctrine of consensus. The framers believed that the larger, broader, and more considered a majority is in support of an initiative, the greater the odds are that that initiative will promote the general welfare. Consensus offers no guarantee, but the chances are higher than for decisions supported by a small, narrow, or fleeting majority. Under this logic, the people do not need a king or an aristocracy to check their actions; what they need instead are institutions that promote broad agreement. That is what the Constitution is designed to do: force majorities to become larger and more durable before they’re able to make any major changes or policies.

If you think of consensus as a central idea underlying the Constitution, a lot of its otherwise peculiar institutions begin to make sense. The House of Representatives was designed to embody the nation at large, under the belief that a diverse country would have a multiplicity of factions, none of which would preponderate. The Senate was intended as a more elitist branch, whose function was to slow down the pace of legislation for the sake of deliberation, thereby checking the potential impetuosity of the people. The presidential veto was designed as a final check on the legislative process. The president is the only national officer under the Constitution (apart from the vice president, who has little real power), so the presidential veto is intended to ensure that legislation reflects the good of the whole community, not just the interests of a majority of congressional factions. And the elaborate system of checks and balances is intended to keep any faction in government from dominating the rest.

Consensus helps explain the important role that the Electoral College continues to play. It is not democratic, strictly speaking. Because the Electoral College provides each state with a minimum of three electoral votes for president, it privileges geographical space over numerical majorities. But in a continent-spanning republic, less-populous regions must be protected. Because they are otherwise outvoted and far from the centers of power, it can be difficult to secure their loyalty, which is essential in a system of government where the consent of the governed is the core of legitimacy. This was the argument of the small states at the Constitutional Convention. Their claim was that they would effectively cease to exist as political, social, and economic units in a government based only on the rule of a national majority. And ultimately, the populous states were forced to consent because without the small states, there would have been no country

A woman reacts to the results of the 2016 presidential election on Nov. 9, 2016 in New York City. (Photo by Win McNamee/Getty Images)

A woman reacts to the results of the 2016 presidential election on Nov. 9, 2016 in New York City. (Photo by Win McNamee/Getty Images)

Fixing the flaws

The same logic still works today. If we want to hold together a country as large and disparate as the United States, we must account for place, as the Electoral College does. It encourages a consensus that considers the geographical scope of the nation. In practice, that means that the East Coast and West Coast cannot govern at the expense of the interior, but instead must build coalitions that draw on flyover country. This is a virtue, not a vice.

The Electoral College, moreover, does not grant the final say in government to geographical minorities. After all, the House is based on population size, so the most populous states overall have a bigger role to play in both the election of the president and in passing legislation.

That doesn’t mean the Electoral College works perfectly, however. Twice in the last generation, it has produced minority presidents who were elected despite having won fewer popular votes than their opponents. That can’t be explained by mere happenstance. Whereas the election of 2000 was so close that either George W. Bush or Al Gore could conceivably have won the Electoral College while losing the popular vote, in 2016, Hillary Clinton won approximately 3 million more votes than Donald Trump but still lost in the Electoral College. Yes, the Electoral College should take geography into account, but not exclusively or in a manner that completely undermines the principle of majority rule. While Clinton did not win a majority of the votes in 2016, she came a lot closer than Trump did.

Does this mean the Electoral College should be abolished, however? The answer is no. Doing so would strip power away from geographical minorities and make the office of the presidency less reflective of the broader consensus the framers were seeking. But the college can and should be reformed. The best way to do this would be by expanding the House of Representatives – which should happen anyway. The size of the House has been fixed by statute for nearly 100 years, despite the enormous growth of the U.S. population during that period. That has made the House less representative of the diversity of the American people. Congress can and should address that in a way that gives bigger states greater sway in both the House and the Electoral College. The winner-take-all feature of presidential elections is also a matter of state law. In the early days of the republic, states often split their electors. Today, only Maine and Nebraska do so. The rest should return to this idea today, since doing so would also make the Electoral College more democratic.

The point to remember, however, is that institutional mechanisms that limit the power of raw democracy can be good if they promote consensus. The Electoral College is intended to help accomplish that. So it should be reformed, not done away with – and in ways that ensure it better performs its constitutional tasks.

A bust of James Madison. (Courtesy of Wikicommons)

A bust of James Madison. (Courtesy of Wikicommons)

COUNTERPOINT

SHOULD THE MAJORITY RULE?

How the Founders viewed elections – and what that vision means for American democracy today.

by Jesse Wegman

There are two definitions of democracy, both from the first half of the last century, that seem especially relevant to U.S. politics today. The first, by the essayist E. B. White, reads, “Democracy is the recurrent suspicion that more than half of the people are right more than half of the time.”

The second, by the more dyspeptic writer H. L. Mencken, declares, “Democracy is the theory that the common people know what they want, and deserve to get it good and hard.”

These definitions work particularly well when set side by side, because together they articulate the duality, the paradox, at the heart of the modern American conception of self-government. On the one hand, that concept rests on a sanguine faith in human nature and the wisdom of the crowd. On the other, it includes a cynical awareness of the dangers inherent in trusting the majority to make decisions in the best interests of everyone.

The American founders struggled with this paradox as they wrote and then rewrote the charter that would govern their young, growing, and fractious nation. The founders believed in popular sovereignty – the idea that governments derive their authority and legitimacy from the consent of the governed. At the same time, however, they were deeply skeptical of the ability of average citizens to vote wisely.

The Constitution that emerged from the long, fraught convention in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787 included features that reflected and responded to both White and Mencken’s definitions. Yet one of these features – the Electoral College – has grown increasingly problematic today, since it is radically out of step with the expectations of people living in a modern representative democracy. It no longer serves a positive function, if it ever truly did, and it deserves to be abolished.

When winner takes all

The basic democratic expectations violated by the Electoral College involve two principles: political equality and majority rule. In the context of elections, political equality means that all votes should count equally – one person, one vote. Majority rule, meanwhile, means that the candidate who receives the most votes should always win. The two ideas are inextricably connected, because majority rule is the only method of counting that assures all votes are treated as equal. Any other method inevitably values some votes (and thus voters) more than others.

The most important founders believed strongly in these principles. Some did so from the start, like James Wilson, who fought for a popularly elected president and said at the 1787 convention, “The majority of people, wherever found, ought in all questions to govern the minority.” Some came to the realization later. In 1833, James Madison, who had watched his design for American government play out in practice for nearly half a century, wrote that “the will of the majority” is “the vital principle of republican government.”

The Electoral College, as it operates today, undermines both political equality and majority rule. It does not treat all votes for president as equal, and it can – and occasionally does, and will continue to – award the presidency to the candidate who receives fewer votes than his or her opponent.

Lt. Gov. Mandela Barnes casts his vote for the presidential election in Madison, Wisconsin on December 14, 2020. (Photo by Morry Gash-Pool/Getty Images)

Lt. Gov. Mandela Barnes casts his vote for the presidential election in Madison, Wisconsin on December 14, 2020. (Photo by Morry Gash-Pool/Getty Images)

That’s not what the Electoral College was originally designed to do. Remember that, in the early days of the republic, the president was not directly elected. Instead, as the founders envisaged it, the Electoral College would vest the choice of president in a small body of politically savvy elites, carefully chosen by other elites in state government, who would deliberate among themselves and pick the best person to lead the country. That design fell apart almost immediately, however, as national political parties developed and presidential electors became little more than rubber stamps for one side or the other. Today, the Electoral College works more or less as it has since 1796, the first election in which George Washington was not on the ballot and candidates from two distinct parties faced off. Each state gets a number of electors equal to the state’s representation in Congress: its members in the House of Representatives plus its two senators. On Election Day, each state holds a popular vote and awards its electors based on the outcome of that vote. To secure the presidency, a candidate needs to win an outright majority of electors nationwide – today, that is 270 out of 538 total.

The winning candidate doesn’t need a majority of votes in the state; he or she only has to earn more than everyone else on the ballot.

The big problem caused by the modern Electoral College is a product of the way all but two states (Maine and Nebraska) now allocate their electors: the winner-take-all rule. This method works the way it sounds. All of a state’s electors go to the candidate who wins the most popular votes in that state, no matter how narrow the margin of victory. The winning candidate doesn’t need a majority of votes in the state; he or she only has to earn more than everyone else on the ballot.

James Madison, a key framer of the Constitution, warned of the distorting effects of this method 200 years ago, when states first started adopting it. (Under the Constitution, states are free to allocate their Electoral College votes using almost any system they choose.) In fact, Madison was so concerned with the trend toward winner-take-all systems that in 1823, he proposed a constitutional amendment prohibiting them. (It was never adopted.)

History, however, has proved Madison right. Just consider the modern artifice of so-called red and blue states. Tens of millions of Republicans live in blue states, and tens of millions of Democrats live in red ones. But when it comes time to choose the president, because the other side has a durable majority in their state, those minority-party voters might as well not exist. As Thomas Hart Benton, a 19th-century Missouri senator, argued, the insult to the minority is even worse than that. “To lose their votes is the fate of all minorities, and it is their duty to submit,” he said in a speech to Congress in 1824. “But this is not a case of votes lost, but of votes taken away, added to those of the majority, and given to a person to whom the minority is opposed.”

The winner-take-all method is the reason why the loser of the popular vote has won the presidency five times in U.S. history so far – and very nearly won it several times more. In 2016, Donald Trump earned almost 3 million fewer votes nationwide than Hillary Clinton, and yet he nevertheless won the election, thanks to razor-thin majorities of fewer than 80,000 votes total in three battleground states – in an election in which almost 137 million people cast ballots. The same thing nearly happened in 2020, when Joe Biden won 7 million more votes nationally but would have lost the election if about 44,000 voters had changed sides in a few key states.

Even when the popular-vote winner does become president these days, the winner-take-all method still distorts the election. That’s because the vast majority of the country is made up of so-called safe states – those that are clearly in the bag for one party or the other. Because the outcome in these states is clear in advance, candidates from both parties ignore the voters who live there, despite the fact that they account for roughly 80% of all Americans. Their interests, concerns, and needs don’t get addressed. Instead, nearly all the candidates’ attention goes to the half-dozen or so battleground states where the winner is genuinely unknown in advance. And even there, almost all the attention gets focused on the few counties that will decide the outcome in those states.

This is no way to run a national election for anything, let alone president. It values votes differently depending on where voters reside, and it sometimes awards the election to the candidate who wins fewer votes overall. While Americans may be hazy on the details of the Electoral College, most now understand that this violation of political equality and majority rule is unacceptable – which is why consistent majorities have supported a shift to a national popular vote for president for as long as the question has been polled.

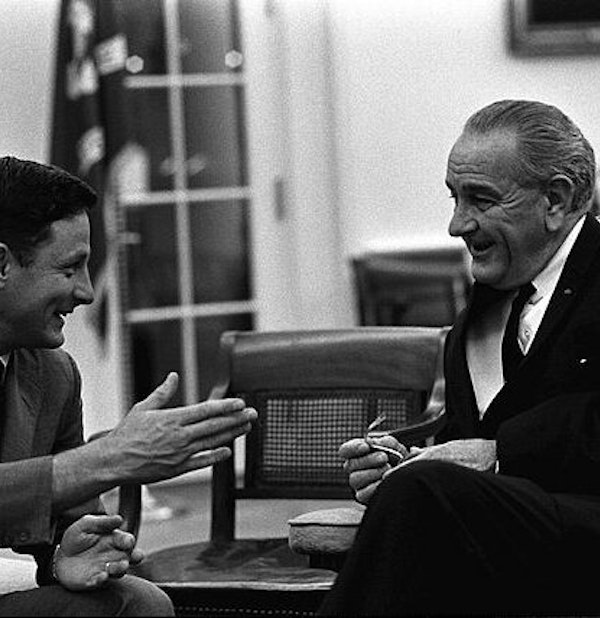

Senator Birch Bayh with President Lyndon Johnson at White House on September 18, 1967. (Courtesy of Wikicommons)

Senator Birch Bayh with President Lyndon Johnson at White House on September 18, 1967. (Courtesy of Wikicommons)

A better way

As former Indiana Democratic Sen. Birch Bayh said in a speech before Congress in 1966, during the last significant push to abolish the Electoral College, a national popular vote is the “logical, realistic, and proper continuation of this nation’s tradition and history – a tradition of continuous expansion of the franchise and equality in voting.”

“The president has no authority over state government,” Bayh continued. “He cannot veto a bill enacted by a state legislature. Why then should he be elected by state-chosen electors? He should be elected directly by the people, for it is the people of the United States to whom he is responsible.”

What of the counterargument that the Electoral College, by overweighting small, rural states, protects the minority from the will of a tyrannical coastal majority? This argument fails for three reasons. First, it’s wrong as a matter of history. The founders did not create the Electoral College to protect the interests of smaller states. Indeed, as several founders pointed out at the 1787 convention, it was not clear what such interests would be. States were aligned with one another not by virtue of size but over policy, most notably slavery. (The slave states did enjoy a boost from the Electoral College, because the three-fifths clause gave them extra representatives for their slave populations, and thus more presidential electors.)

Second, the argument is wrong about the facts on the ground today. As I explained above, the main beneficiaries under the current system are not small states – or, for that matter, medium or large states. Only in battleground states, where the electorate is evenly divided by happenstance, do voters enjoy real extra clout. It’s true that the smaller states get a small benefit from their two Senate-based electors; this is what people are talking about when they say a vote for president in Wyoming counts nearly four times as much as a vote in California. But this benefit is negligible compared with the effect of the winner-take-all rule.

Third, the argument is wrong as a matter of theory. Most Americans are not good at estimating the relative size of the states and the urban and rural populations of the country. In fact, the American people are divided almost exactly into four quarters: urban, suburban, small towns, and rural areas. Today, urban areas vote about 60-40 for Democrats and rural areas vote about 60-40 for Republicans. In other words, they cancel each other out. No one is dominating anyone else.

There is no morally relevant criterion for treating votes as more or less valuable because of where they are cast.

But let’s say, for the sake of argument, that voters in the big cities did happen to outnumber those in rural areas. So what? That’s what majority rule means. There is no morally relevant criterion for treating votes as more or less valuable because of where they are cast. One person, one vote – that’s the principle that governs every other election in the country, and it should be the practice in the biggest one of all.

So the Electoral College deserves to go. The problem is how to make that happen. A constitutional amendment is not politically feasible today, because the Democratic Party is the only one to have suffered under the current system (most recently in 2000 and 2016). If a Republican candidate had recently won more votes nationally but still lost the Electoral College, the movement to switch to a national popular vote would likely be bipartisan.

Fortunately, Americans have other options for addressing the distortions caused by the Electoral College under the winner-take-all rule. As mentioned above, states have virtually unlimited authority to decide how they allocate their electors. Indeed, a movement has already arisen to ensure the selection of the president on the basis of a national popular vote – without touching the Constitution.

Patricia Whitefoot casts her Electoral College vote in Olympia, Washington on December 14, 2020. (Courtesy of Wikicommons)

Patricia Whitefoot casts her Electoral College vote in Olympia, Washington on December 14, 2020. (Courtesy of Wikicommons)

This effort, which started 20 years ago through the work of a computer scientist, relies on something called an interstate compact: a common method by which states agree to cooperate with one another on policies that are mutually beneficial. (For example, numerous states have joined a state lottery compact, and New York and New Jersey formed one to create the Port Authority, which helps manage the large transportation infrastructure in the region.) In this case, states that join the popular-vote compact agree that they will award all of their electors to the candidate who wins the most votes in the nation as a whole, rather than to the candidate who wins the most votes in their state. It’s still winner-take-all but at the national level, which is appropriate since the election is for America’s only national office. The compact will only take effect when it is joined by states representing a total of at least 270 electoral votes – the number required to win the presidency. What this means is that the candidate who wins the most votes in the country will, by definition, win at least 270 electors (since all states in the compact will award all their electoral votes to that candidate) and, therefore, the White House.

At the moment, 17 states and the District of Columbia have signed on to the compact, representing a total of 205 electoral votes. If states with 65 more electoral votes join, the compact will take effect. And that, in turn, will force presidential candidates to campaign across the nation and to treat all voters as equally important, no matter where they live.

Even if the drive to achieve the interstate compact reaches the critical threshold, several hurdles will still remain. Opponents have pointed out that the Constitution requires that Congress sign off on any interstate compact. There are arguments for and against this position, but the matter could be resolved by getting Congress’ approval beforehand. Unfortunately, given the current polarization of that institution, it’s hard to imagine that happening.

An even bigger obstacle involves a scenario in which voters in a participating state choose one candidate but the majority of voters in the country choose the other. In that case, under the rules of the agreement, the state in question would award its electors to the candidate who lost there. That outcome could cause a majority of the state’s voters to feel their votes were stolen from them.

This would be an understandable reaction. The solution is to help the American people realize how most of us already think of the presidential election, even if we do so unconsciously. How? By asking people a simple question: Why did you vote the way you did? No one will answer that question, “Because I wanted my candidate to get more votes in the state I live in.” They know it’s irrelevant, even if they have not articulated it before. When President Trump won in 2016, Republicans in, say, Massachusetts were happy with the result. They didn’t care that their own state went for his opponent. The same goes for Mississippi Democrats in 2020, who celebrated the national outcome even though more voters in their state chose President Trump. The point is that Americans vote for the candidate they want to win. They understand that the presidency is a national office, and they vote accordingly. If that’s how the votes are cast, that’s how they should be counted.

Political equality and majority rule remain the lodestars of any representative democracy and are the best reasons to fight for a popular vote.

Unfortunately, the same political polarization that makes any constitutional amendment highly unlikely may also undermine the interstate compact. All 17 member states (and the District of Columbia) that have joined the compact so far did so under Democratic leadership. And no wonder: Given that Republican candidates have lost the national popular vote in seven of the last eight presidential elections – the longest streak in American history – Republicans have no incentive to change things.

And yet demographics and politics are in constant flux. If Democrats become the majority in a state like Texas, as political trends suggest could happen in the near future, Republicans will lose all viable Electoral College paths to the White House. The case for switching to a popular vote might then hold greater appeal.

Political equality and majority rule remain the lodestars of any representative democracy and are the best reasons to fight for a popular vote. Most political battles, however, are not won on high principles but on the alignment of self-interest among the key players. And if that’s what it takes to change the system, Americans will still be far better off. In the meantime, as the divergence between the counter-majoritarian design of the U.S. political system and the expectations of the American people continues to grow, the pressure for change will become impossible to ignore.

The Catalyst believes that ideas matter. We aim to stimulate debate on the most important issues of the day, featuring a range of arguments that are constructive, high-minded, and share our core values of freedom, opportunity, accountability, and compassion. To that end, we seek out ideas that may challenge us, and the authors’ views presented here are their own; The Catalyst does not endorse any particular policy, politician, or party.