#HowAreTheKids: Keeping an Eye on the Big Picture in Education

School boards, parents, and policymakers all want the same outcome: healthy, well-prepared, well-adjusted children in our community. As debate continues and evolves around educational topics, Stewart reminds us to stay focused on children.

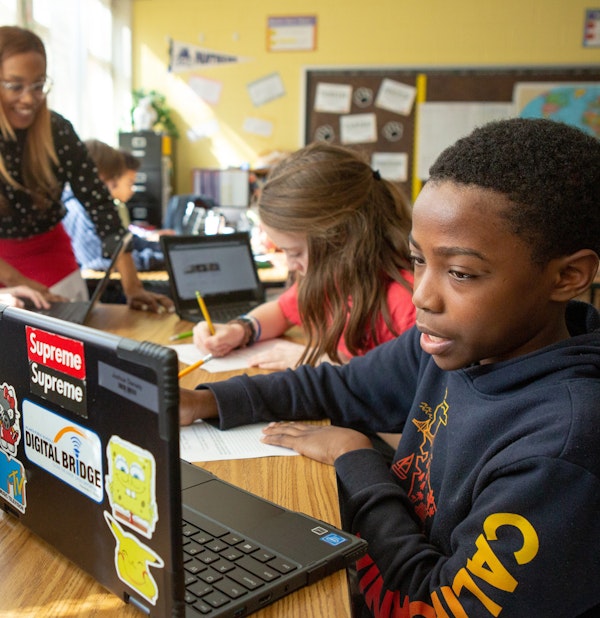

Students use online research to answer questions during a lesson in history class. (Allison Shelley / American Education: Images of Teachers and Students in Action)

Students use online research to answer questions during a lesson in history class. (Allison Shelley / American Education: Images of Teachers and Students in Action)

Chris Stewart is the CEO of brightbeam, a nonprofit network of education activists demanding quality schools for every child. The self-described parent activist served on the Minneapolis school board and now sits on the board of Great Schools. He also led the African American Leadership Forum (AALF), worked for Education Post, and actively tweets under the handle @citizenstewart.

Stewart had a candid conversation in July with Anne Wicks, the Ann Kimball Johnson Director of the Education Reform Initiative at the Bush Institute, and William McKenzie, senior editorial advisor at the Bush Institute.

Below are excerpts from their discussion, which has been edited for length and clarity.

People have been working on education reform for decades. At the same time, these pervasive, persistent achievement or opportunity gaps occur and stay around. Why do you think that is? What’s important to you to change?

If you look over time, you do see that there’s been upward trajectory of Black students. If you took White students out of the mix completely, it would look like Black students are improving over time. I think it would be important to look at decades of time, or in discrete sections of time, to see what was really happening.

There’s some who argue that when you see the bigger increases in Black student achievement in the ’70s and ’80s, that’s because of integration, which isn’t true. It’s important to point out that for years and years, White student performance was very flat, and Black performance and Latinos scores were increasing because they were becoming more middle class, more union jobs, the whole works. And there would be an endpoint to how much that would give you a bump. The gap was closing because White scores were flat. When the White scores started improving too, then of course, the gap was going to be more stable in a time when everybody is doing better.

But, if you look at a few periods of time in the ’90s and 2000s, there are a few years where there were bigger upticks that we really need to pay attention to. If you were to study those, it would be a different question in talking about the achievement gap. You wouldn’t just be talking about achievement. Why did your achievement swing up in these periods of time? Why was it happening?

The thing about testing, its role, and how we understand achievement and the outcomes, is that the testing isn’t the outcome. It’s not like my thermometer changes the weather. My scale doesn’t make me slim. I have a scale, I get on it, and it tells me bad news sometimes, but I don’t curse the scale. I curse my diet. People need to get their minds around the same thing with testing, because you will have opponents who will say things like, “We’ve done all this testing for all these years and there’s still a gap and nothing has changed.” As if the actual administering of the test was supposed to be the thing that made the change. The public needs to be clearer on that. I think analogies work. I do think that it’s appropriate for them to say the scale doesn’t make you lose weight.

My scale doesn’t make me slim. I have a scale, I get on it, and it tells me bad news sometimes, but I don’t curse the scale. I curse my diet. People need to get their minds around the same thing with testing.

You famously use the hashtag #HowAreTheChildren when you’re talking about education reform and education issues. Why is that important?

I think it’s the most important centering conversation if we’re going to talk about children, period. If we’re going to have these education debates, I think people are going to go on a lot of tangents and the room is going to be confused eventually. What is the outcome that we want? We want healthy, well-prepared, well-adjusted children in our community. When I ask you #HowAreTheChildren, if you are a leader, you need to either lead or leave if that answer is wrong, if that answer is bad. I think it’s a conversation-stopping question in my mind, when people are getting too fancy, when they want to talk about everything in the world except for the outcome of the children that are in their jurisdiction.

I also had a hashtag called #PassTheTest. I was trying to convince the public to say that the problem isn’t the test, the problem is that our kids are brilliant, they can learn, and they can pass the test if we taught them. Let’s stop talking as if it’s impossible for them to pass this test and stop creating all kinds of imaginative barriers like “it’s the culture,” “they don’t know the difference between a pail and a bucket,” all that type of stuff. That’s not it. All of our kids are born with brains that are elastic, that can grow, and can take in new information to learn.

#HowAreTheChildren is for adults to get clear about what they are on the hook for and accountable for, especially as leaders. Then, #PassTheTest was my way of getting the public to say we must close the belief gap. We must close the gap between what our kids are capable of, and what the systems think they’re capable of.

What is the outcome that we want? We want healthy, well-prepared, well-adjusted children in our community. When I ask you #HowAreTheChildren, if you are a leader, you need to either lead or leave if that answer is wrong, if that answer is bad.

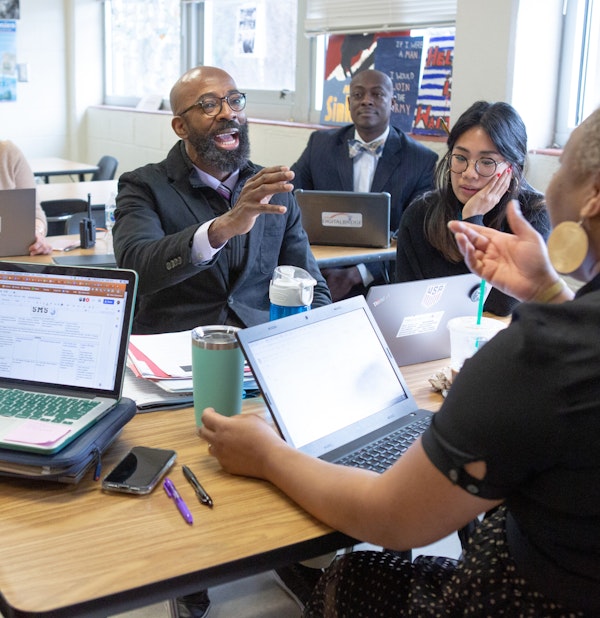

Chris Stewart leads a session of educators in Nashville, Tennessee, in October 2019. (via Twitter @citizenstewart)

Chris Stewart leads a session of educators in Nashville, Tennessee, in October 2019. (via Twitter @citizenstewart)

You served on the school board in Minneapolis, and I’m curious how that experience has informed the work you do now. How do you think about the role of local governance and school board members?

I think for any normal citizen, any regular citizen, it would be quite shocking once they’re on a board to see what actually happens behind closed doors. It’s one of the most essential parts of the democracy in any city. I couldn’t see more widespread ignorance about that institution until you actually get on the board and see it from the inside. You get to see how much people don’t know, how much of it is not about children. It’s about legacy obligations, legacy debts, legacy bargaining units. We had 16 bargaining units in Minneapolis; one had only one member. I keep saying that because it still astounds me that we had a bargaining unit with one member in it. One guy was a union.

The longer you sit there, you come to realize that we haven’t even touched a real child-centered question. That’s kind of shocking as a parent who runs for school board and wins, or an activist who runs for school board and wins.

This is a really tough question for me because I lost my belief in the system by being a school board member. Even the journalists, who often know what’s really going on, don’t tell the stories to make the public smarter about one of the main institutions in the middle of their cities. There are things we need to know about how decisions are made about curriculum, about what buildings get what, about what kids deserve what levels of instruction, and about how to put teachers who we know are underperforming in a place where no one’s going to scream about it.

Decisions like that compound inequities the more of them that you add on top of each other. I really don’t believe that people are aware of just how unprepared the people they elect to school boards are to govern. Many states have a law about the training school board members receive once they are elected. That training is so insufficient. It’s such a joke. If you are talking about the people who are responsible in their jurisdiction for the lives of children, I don’t think the public understands to the extent that they are not ready for that job. They’re not prepared. They’re not trained.

In one of my very first meetings, the superintendent gave us a thick binder that was the budget. He wanted us to pass it that night. I’m supposed to read this in 15 minutes? It’s a $700 million budget. I’m going to have a few questions. Of course, we didn’t pass it that night, but it got me to think about just how infantilized school board members are by the administration often. You’re kind of window dressing in a lot of ways. I don’t think that that’s what the role is supposed to be.

It also amazes me the extent to which every couple of years, there was the expectation that everything was going to get washed away and started over again. A new superintendent was going to come in with a new PowerPoint, and suddenly the district was going to do something totally different. And then three years later, they notice that it didn’t work so another superintendent will come in with a new PowerPoint. If you just rinse, wash, and repeat over a period of time, there’s no stability.

Middle school history teachers discuss their lesson plans for teaching about the Great Depression. (Allison Shelley / American Education: Images of Teachers and Students in Action)

Middle school history teachers discuss their lesson plans for teaching about the Great Depression. (Allison Shelley / American Education: Images of Teachers and Students in Action)

If it wasn’t for test scores, imagine that. If it wasn’t for test scores and longitudinal data, every three years, you’re having new administrations come in and do wildly different things. The data’s the only thing that stays consistent. How are the children? That’s the only question that stays consistent through all those seat changes.

The data’s the only thing that stays consistent. How are the children? That’s the only question that stays consistent through all those seat changes.

When you think about the work with you do with and for families, what do families need? Particularly families of color, Black families, Latinx families, families living in poverty, what do they need? And how does your answer change when you think about that in a COVID world?

I think that they need every opportunity possible to get their kids into an education environment that has some reasonable expectation that it’s going to be quality, and it’s going to be better than where they are assigned. We have education deserts on purpose, because of the way we assign students to schools based on their address.

If I think about the people that are trapped in those education deserts on purpose, the only thing that I can see that’s powerful to offer them is the ability to get out of their assigned place in the educational world. That’s one of the biggest fights, because any time you start doing that, you bump up against powerful interests that don’t want students to move any direction. Their job is to stay put right where they are, whether it’s working for students or not, because we need to harvest their per pupil income.

You open a school choice program, it fills up. You open an opportunity somewhere outside of the city or somewhere else, it fills up. That tells you that the people know they want something else. When you open up an opportunity, the families flood the gate, which tells me that the best thing I can offer families is power to be the decider. You get to be the president of your child’s education. You can give them options and opportunities that are better than what they are assigned, because we all know that those options are really bad. We know that low accountability schools in education deserts are immoral, and they have no reason to be responsive to your desire for your kids to do better.

When you open up an opportunity, the families flood the gate, which tells me that the best thing I can offer families is power to be the decider.

The more you see school choice programs across the country, you see the different constituencies that they work for, and for different reasons. I think that’s important to keep in mind. Whether your kid has dyslexia, or is gifted and talented, or is super bright and not fitting in, or is being bullied, or wants to do more math or science or whatnot, it drives the idea that families should have more educational opportunity. I call that parental sovereignty, which is what I focus on when I work.

When I took the job at brightbeam and came back to educational activism, I thought education reformers were losing focus. I likened it to the Tower of Babel. They were getting too close to heaven, so God confused their language, and then they all went different directions. And that was going to be really bad for us, in my analysis, when people started arguing about, “Is testing good? I don’t know. Are charter schools good? I’m not sure.” We lack clarity that our opponents have.

Our opponents have what I’ve called an “ISIS level of clarity” about who is good and who is bad in their world. The reform world is the exact opposite. We live in such nuances and die in nuances that we can’t speak straight and keep a movement together. When I came back, I wrote a piece that said, “It is time to charge the hill, plant a flag, and stand for kids again like we’ve been doing for all these years, and let the weak ones and the simps fall back.” God has no use for lukewarm people, so fall back if you’re not with it and you can’t do it.

As a leader, there are some battles that you have to fight even if you think you’re not going to win. Right now, we have a lot of people in the reform world who think we should trade out some of these issues so that we can find more common ground and we can be more likable. That feels like if I just did my makeup differently, he wouldn’t hit me, which is a really ridiculous way to see the world. They’re never going to like us. And, it’s never going to be wrong for us to assess our kids. That’s never going to be the wrong thing to do.

As a leader, there are some battles that you have to fight even if you think you’re not going to win.

I am watching NCLB, for instance, go from a hope-driven, practical application of bipartisan policy that was meant for all kids, to being completely recast by opponents as being draconian and misguided and ill-intended. Even reformers are taking up that line now. That tells me where we are with reform right now.

I think we need a big tent, but I don’t think we need everybody. I wonder if the real people will stand up and come forward and charge the hill, plant the flag, and stand for kids?

I think we need a big tent, but I don’t think we need everybody. I wonder if the real people will stand up and come forward and charge the hill, plant the flag, and stand for kids?