A Report Series on Lessons Learned from PEPFAR’s Success

Introduction

Many speak of the importance of “sustainability” and “country ownership” in foreign assistance – often in the same sentence – but these terms have become empty buzzwords with multiple interpretations. Does “sustainability” speak to the long-term funding responsibility that should lie with implementing countries or to the ability of a program to function in a crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic? Does “country ownership” mean solely public sector government control or ensuring a legitimate collaboration between governments, civil society, communities, and the private sector in designing and implementing development projects?

Deep community engagement is at the heart of both sustainability and country ownership in the best-structured development programs. PEPFAR offers a model for local ownership, sustainability, and impact that is relevant for all areas of global health and development.

In that regard, PEPFAR has increased the share contributed by national governments and taxpayers in partner countries, used innovation to maintain services through an unprecedented crisis, and created ways for all groups to fully invest in and be part of programming.

This report, part of a series on PEPFAR, focuses on the lessons learned that are applicable to all areas of international development. These lessons center on partnership through PEPFAR between the people of the United States and communities abroad – as well as on PEPFAR’s role in facilitating transparent and effective communication between host governments and communities. The report discusses PEPFAR’s client-centered approach to programming, including the importance of prevention to control the HIV pandemic and continuous improvement in the delivery of lifesaving treatment. It stresses the importance of building truly local capacity, including how PEPFAR used experience gained from its original emergency treatment grants (known as “Track 1”) to make a revolutionary push to finance local implementers.

Global Vision, Local Implementation

President George W. Bush’s vision from the beginning was that PEPFAR would invest in communities most affected by the HIV/AIDS pandemic and help people help themselves. PEPFAR was meant to inspire what the president called “America’s armies of compassion”: helping save millions of lives overseas by supporting courageous people whose countries seemed near collapse under the crushing burden of HIV/AIDS in treating the sick, preventing new infections, and caring for those left orphaned and vulnerable.

Because many patients with HIV were already close to death, the president outlined an emergency response plan in his January 2003 State of the Union address. A fact sheet that accompanied the speech described PEPFAR’s “network” model, which would link existing public-sector, nonprofit, and private-sector Central Medical Centers (CMCs). In a hub-and-spoke system, these CMCs would be surrounded by satellite centers and even mobile units arrayed in concentric circles from cities to rural areas.

The most important element of the plan was that the core network facilities already existed. To move as quickly as possible, the president envisioned supporting these CMCs and their referral networks, many of which were faith-based hospitals, with training, equipment, test kits, medicine, and technology to allow them to find and enroll thousands of clients on antiretroviral treatment (ART) immediately. Prevention activities were to follow a similar model that would harness the legitimacy and trust built by grassroots nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), faith-based organizations (FBOs), and community leaders to educate people on how to keep themselves and their families safe. The program’s goal was to enable the establishment of “comprehensive indigenous network systems” through partnerships with host governments, NGOs, FBOs, and communities themselves, according to PEPFAR’s first Annual Report to Congress.

The new Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator (S/GAC) created in the U.S. Department of State to manage PEPFAR moved quickly to implement this model once Congress appropriated the first resources for the program in January 2004. After a year, more than 47% of the prime recipients of PEPFAR funds were local, according to the Annual Report, as were 83% of subpartners under nonlocal prime partners. This meant that more than 1,000 of PEPFAR’s 1,200 total prime and subrecipient partners, or 80%, qualified as “local” under the definition the program used at the time. Nevertheless, both direct and sub awards to local partners tended to be small, and most resources flowed through large awards to U.S.-based and international organizations.

To promote long-term sustainability through the transfer of knowledge and skills to local groups, PEPFAR began early on to insert what it called “graduation” language into its contracts, grants, and cooperative agreements with international partners. These provisions meant that at least part of the evaluation of the performance of nonlocal organizations would depend on their success in preparing their local subpartners to take on more responsibility for the delivery of services. By 2006, PEPFAR teams could allocate a maximum of 10% of the budgets of their annual Country Operating Plans (COPs) to any one partner (with certain exceptions), which decreased the size of awards and increased the chances that local organizations would be competitive in responding to funding announcements.

The Emergency Plan prioritizes the development of new partnerships with local groups and organizations as a key strategy for increasing access and building sustainability.

–PEPFAR’s first Annual Report to Congress, 2005

Localizing Responsibility for Treatment

PEPFAR’s initial and most urgent task was to jump-start lifesaving treatment. Saving as many lives as possible was PEPFAR’s mandate in those early days – ensuring moms and dads were there to raise and support their families and that children received medicine so they could not only survive but thrive. S/GAC responded immediately to prepare the groundwork for implementation, not even waiting for a congressional appropriation. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), both components of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), published the first Request for Applications (RFA) in September 2003 to provide lifesaving antiretroviral therapy (ART) under PEPFAR.

Entitled “Rapid Expansion of Antiretroviral Programs to HIV-Infected Persons in Selected Countries in Africa and the Caribbean Under the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief,” the RFA was meant to build on the head start provided by the $500 million International Mother and Child HIV Prevention Initiative launched by President Bush in 2002. The intention of the competition was to fund organizations that already supported the distribution of ART or prevented the transmission of HIV from mothers to their children in the 14 original PEPFAR focus countries. A particular focus was those working in and through CMCs and their hub-and-spoke networks. Language in the funding notice gave priority to local groups and emphasized the need for applicants to have on-the-ground experience.

Four U.S.-based winners emerged from the RFA to carry out what became known as the “Track 1.0 Care and Treatment Program.” Catholic Relief Services (leading a consortium called “AIDS Relief”), the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation (EGPAF), ICAP at Columbia University, and the Harvard School of Public Health each received a five-year award worth approximately $350 million in early 2004 to roll out or expand ART in multiple countries. Although the Track 1.0 partners had relationships with CMCs and other hospitals and clinics across parts of sub-Saharan Africa and the Caribbean, some in rural areas, none of them was truly local. This approach harnessed the knowledge and capacity of treatment in the United States, which had been ongoing for nearly a decade, and translated it through training and adaptation to Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean.

What happened to the priority for local groups? In retrospect, the drafters of the RFA underestimated the vast experience of U.S. universities in writing grant applications. They also were naïve about the ability of local organizations to compete for U.S. Government awards; many such groups did not yet have the administrative or financial infrastructure to manage U.S. funding at the scale that was necessary to get PEPFAR off the ground. As a result, local NGOs and FBOs would have to begin by playing a subordinate role in the treatment component of PEPFAR as subrecipients under the prime awards to the four Track 1.0 implementers.

Under the close watch of S/GAC and PEPFAR in-country teams, the four U.S. organizations collaborated closely with national ministries of health, provincial health authorities, and indigenous FBOs and NGOs. Extensive mentorship and training were critical to this approach. The resulting progress in initiating clients on treatment was swift. By January 2007, PEPFAR was directly supporting treatment for 1.4 million people and had achieved President Bush’s initial goal of 2 million people on ART by the end of 2008, as asserted in PEPFAR’s annual reports to Congress in 2008 and 2009. Nevertheless, the Track 1.0 partners had not made as much progress as originally envisioned in creating local institutional capacity to manage the HIV/AIDS pandemic.

When it came time to renew or recompete the prime awards to the U.S.-based Track 1.0 implementers, the leadership at S/GAC decided to make a change. At the direction of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator, the agreement signed to transfer money from S/GAC to HHS and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) required that the agencies shift away from the Track 1 U.S.-based partners. However, only HHS rapidly adopted and complied with the mandate. The CDC and HRSA transformed their cooperative agreements into terminal transition awards: Each American organization would receive four more years of funding, but would have to transfer full responsibility for all activities to local partners by the end of that period without any drop off in the quality or coverage of services. The Track 1.0 prime partners would have to prepare their existing subrecipients to receive U.S. Government funding directly and/or help create new local groups and train them to take over.

This transformation was not without controversy. The four Track 1.0 partners did not want to lose their lucrative reimbursements for indirect costs and eventually have to compete with their subrecipients for funding. The CDC teams in the field who worked on PEPFAR worried about an increased workload, including expanded oversight of grants and cooperative agreements. Some outside observers questioned the ability of local organizations in Africa and the Caribbean to manage Federal awards and raised concerns that waste, fraud, and abuse would multiply. Despite agreeing to the policy by signing the agreement to transfer funds from S/GAC to implementing agencies, USAID declined to adopt a similar approach for its Track 1.0 programs for HIV prevention and care for orphans and vulnerable children, or for its subsequent ART initiatives funded under PEPFAR.

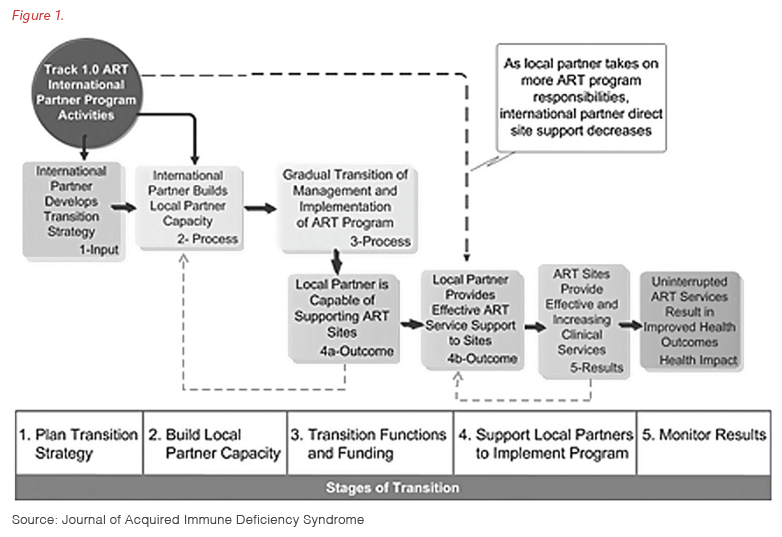

To their great credit, the four Track 1.0 organizations, the CDC, and HRSA embraced the opportunity and changed their business models, both at headquarters and in the field. As shown in Figure 1, AIDS Relief, EGPAF, ICAP, and Harvard adopted a careful, five-step process to manage the transition of funding and service delivery to local partners based on diligent oversight and analysis of data. The Track 1.0 prime partners shifted their role to technical support only as each indigenous subrecipient learned to carry out programming at the same level of quality while also continuing to expand the number of people on treatment. In some cases, such as with EGPAF, the Track 1.0 organizations helped to found, spin off, and mentor local versions of themselves, with entirely separate legal status, local staff, and local boards of directors. In other cases, ministries of health assumed direct responsibility for the activities formerly undertaken or supervised by outsiders.

The U.S. Government agencies had to adapt as well as they moved from multimillion-dollar umbrella cooperative agreements to smaller individual awards. This included streamlining policies and practices and bringing on board more staff members with different skills, many of whom were local hires, to manage the growing relationships with local partners and oversee their performance. The CDC staff in the field had to become more directly engaged with local funding recipients in a more substantive manner, offering more hands-on supportive supervision in both technical and administrative areas and traveling farther from the comfort of national capital cities.

By 2011, local partners had taken over service delivery at over half of the 1,300 hospitals and clinics in 13 countries that were treating more than 900,000 HIV-positive clients under the Track 1.0 awards, according to researchers. PEPFAR successfully transitioned the rest by the end of the Track 1.0 cooperative agreements in 2014, in what was one of the most well organized and successful transfers of capacity and responsibility to local organizations in the history of U.S. foreign assistance.

Infusing Localization Throughout the Entire PEPFAR Portfolio, 2016-2021

Despite early commitment and the recent success of the transition to local organizations under the Track 1.0 awards, PEPFAR’s portfolio had been consolidating in the hands of international NGOs over the years. Fewer than 15% of the prime recipients of PEPFAR funds managed by USAID were local partners in 2016. The percent of prime recipients under the CDC, however, was significantly better (over 50%), because of the success of the Track 1.0 transition.

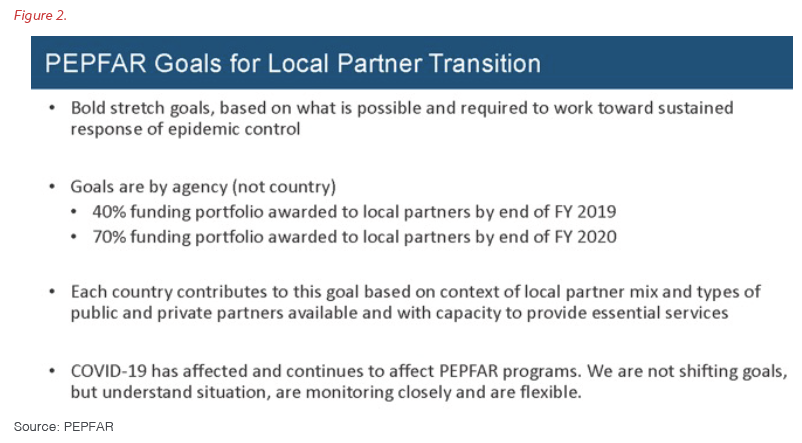

In 2016, the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator tasked USAID and the CDC with undertaking one of the most ambitious transformations in the history of U.S. foreign assistance. To build on PEPFAR’s original vision of supporting a truly locally led response to the HIV/AIDS pandemic, S/GAC set a goal for 70% of each agency’s portfolio to transition to local partners by the end of the implementation period of PEPFAR’s 2020 Country Operational Plans (COPs). Interim targets were 25% for the 2018 COPs and 40% for the 2019 COPs. It is important to note that PEPFAR did not change any of its targets for treatment, prevention, serving orphans and vulnerable children, and other core interventions because of this shift. As with Track 1.0 for ART, the local organizations assuming responsibility for activities would have to maintain quality levels and expand their reach – although S/GAC recognized the need for flexibility and patience. Figure 2 shows the guidance provided to the PEPFAR field teams.

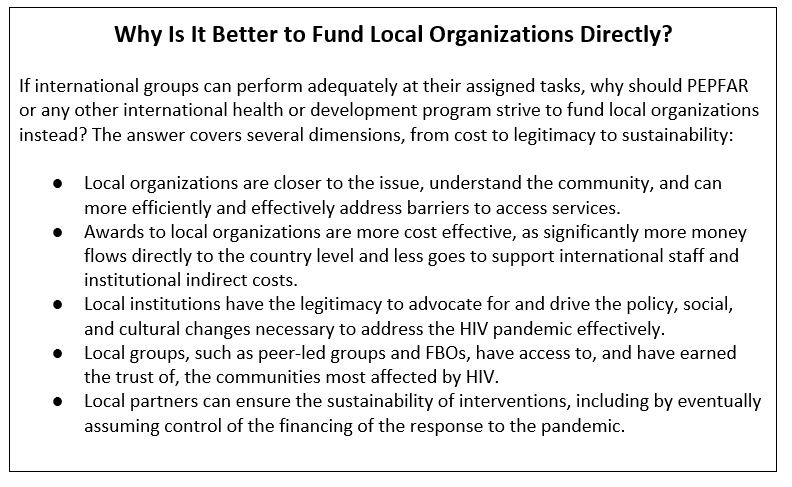

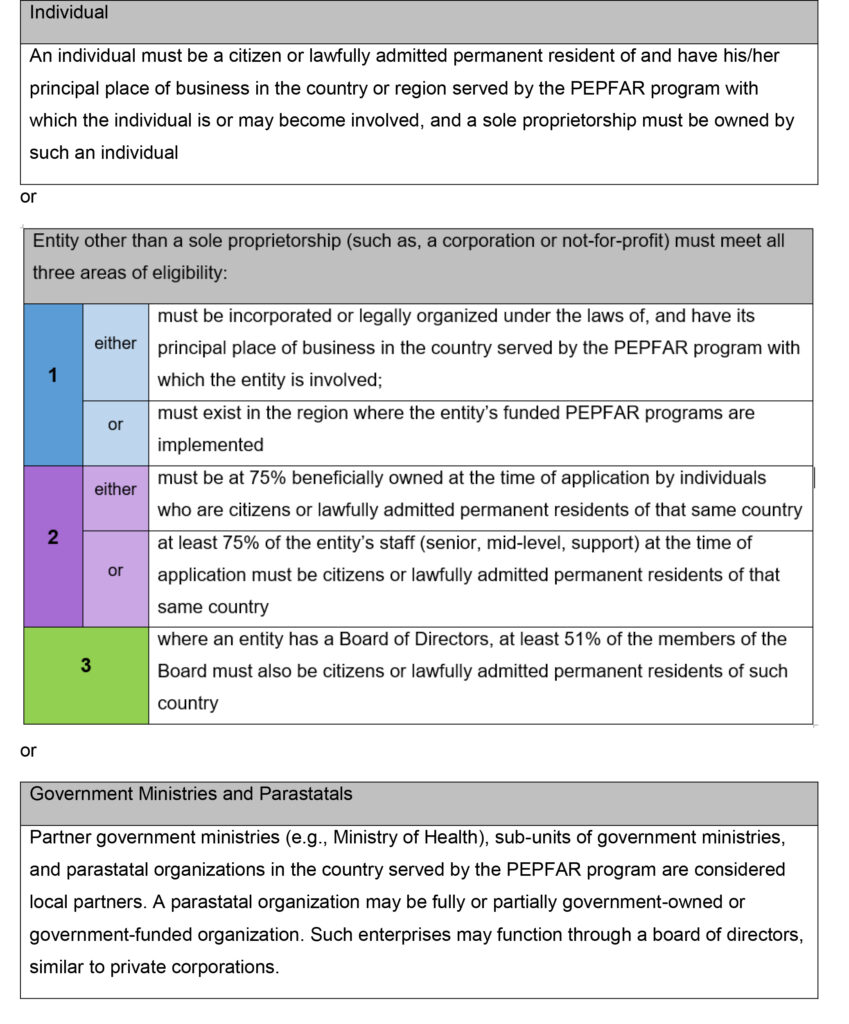

A critical element to PEPFAR’s localization plan was a clear definition of what qualifies as “local,” an important lesson learned from the experience with Track 1.0. The text box below details the standards PEPFAR has been using over the last seven years to judge whether an organization is local. PEPFAR’s definition of local institutions includes government agencies, at both the national and subnational levels, as well as peer-led groups and private-sector and community organizations, including FBOs.

PEPFAR’s Definition of a “Local” Partner

Under PEPFAR, a “local partner” may be an individual, a sole proprietorship, or an entity. However, to be considered a local partner, the applicant must submit supporting documentation demonstrating the organization meets at least one of the three criteria listed below at the time of application.

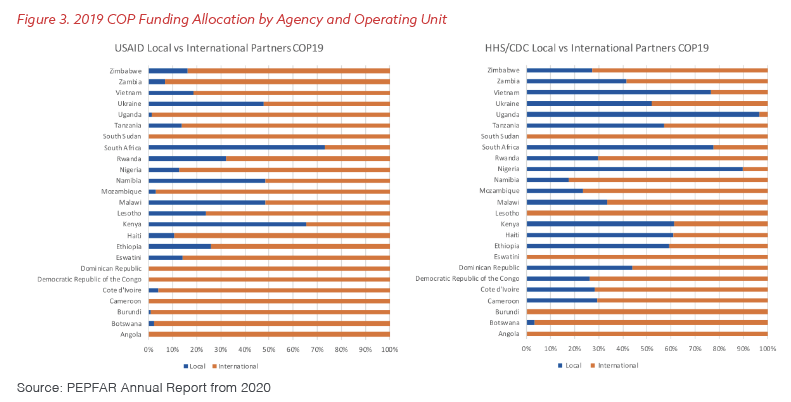

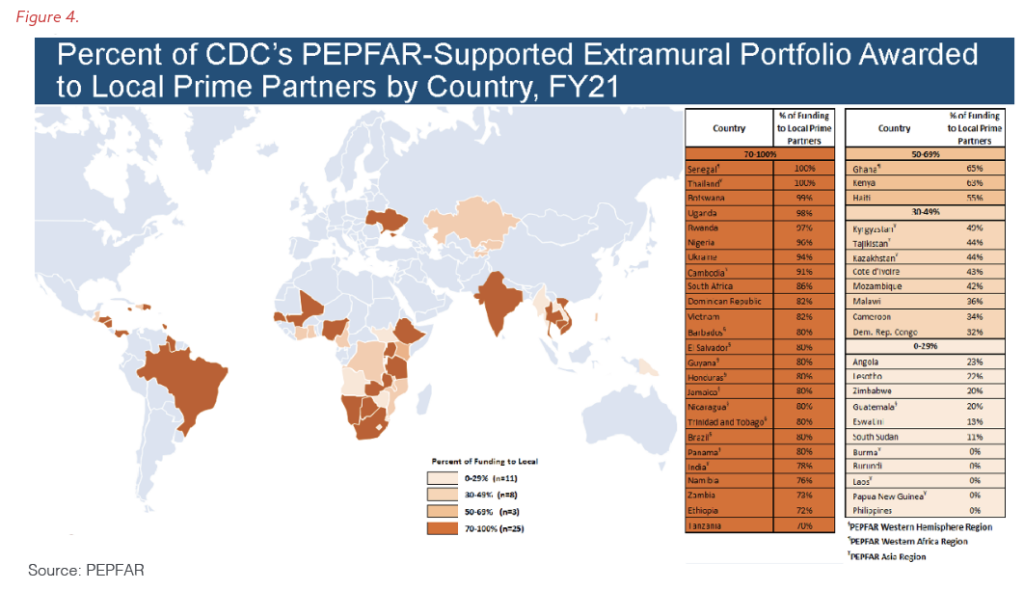

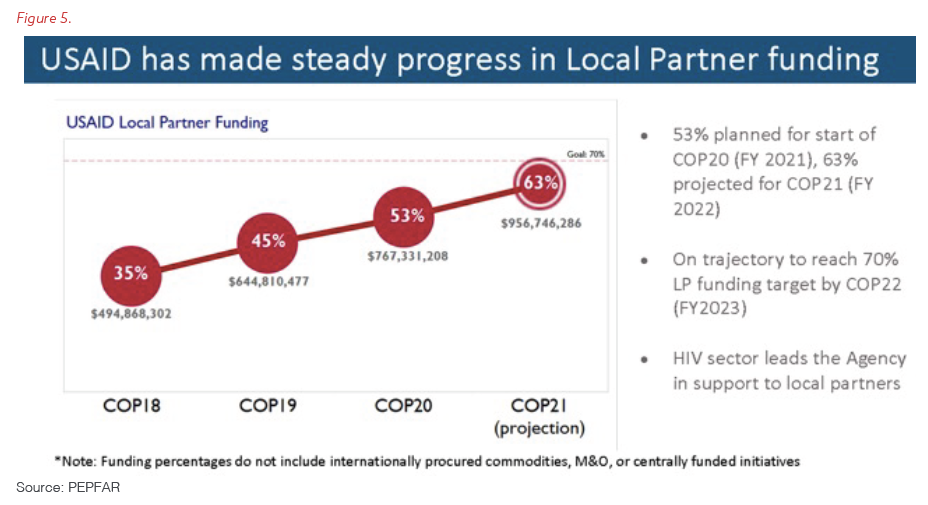

Figures 3, 4, and 5 show the remarkable progress PEPFAR has made in the last seven years to transfer its global portfolio to local implementers. By 2021, the CDC had achieved the 70% target in 25 countries, while USAID transitioned more than 63% of its worldwide PEPFAR awards to local implementers and is on track to hit 70% this year. As a point of comparison, a USAID official testified before Congress in March 2022 that local organizations manage less than 5% of the agency’s total investments around the world (a figure that includes PEPFAR-funded awards).

PEPFAR has made sure to prioritize engaging local organizations in its specialized, multi-country efforts as well. An example is the Determined, Resilient, Empowered, AIDS-Free, Mentored, and Safe (DREAMS) public-private partnership formed to reduce new HIV infections in adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) from communities with a high burden of the disease. To find new ideas and build the capacity of community-based groups, PEPFAR, Johnson & Johnson, and ViiV Healthcare launched the DREAMS Innovation Challenge in 2017. Almost two-thirds of the 55 winners of the competition were small, local NGOs, close to half of which had never received funding from PEPFAR before.

One area for additional improvement is the global supply chain that PEPFAR uses to procure and distribute ART, other drugs, HIV test kits, and medical supplies, currently managed under a multibillion-dollar central contract from USAID. The increasing sophistication of international trade to and from Africa, Asia, and Latin America means that local and regional companies can safely and professionally handle the procurement, storage, and delivery of drugs and health material at a lower cost than a U.S. contractor. As USAID continues the process of bidding out its revised series of contracts for its global health supply chain, the U.S. Government has an important opportunity to save the taxpayer money and contribute to economic growth led by the private sector in PEPFAR countries by choosing local solutions.

Ensuring Localization Under PEPFAR Is Sustainable and Effective

Localization must not bring with it a watering down of PEPFAR’s standards for financial management and probity. Maintaining excellence in performance, quality of service, and access for affected and at-risk populations remains paramount no matter what kind of institution is responsible for implementing a PEPFAR-financed intervention. Change can be difficult and requires the continuous use of granular data down to the site and client level to ensure programmatic improvement; maintain high-quality care; and root out fraud, waste, and abuse.

PEPFAR addresses these risks through a dual approach – the constant use of detailed data and continuous engagement with clients and the community. Essential to this model is the active engagement of communities in the process of building the annual individual COPs. Each PEPFAR field team organizes a strategic-planning retreat that includes host governments, local NGOs, FBOs, and community leaders to plan, review progress, and create an environment of exchange that transcends the public sector alone. The stock taking and approval process for the COPs also convenes sessions with national stakeholders, a lesson learned from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria. In fact, NGOs, FBOs, and representatives of government ministries often present during the meetings and engage fully in an active, weeklong dialogue to make refinements and improvements in real time. Sessions that bring regions together allow for exchanges across countries so PEPFAR teams and partners can learn from each other over coffee, lunch, and dinner. In the design stage of most awards, PEPFAR staff similarly reach out to affected communities and local leaders to gather their insights before publishing an RFA or similar funding opportunity. These conversations are crucial parts of PEPFAR’s approach to continuous quality improvement, as they often reveal what has been working in current programming and what needs to change. In many cases, PEPFAR teams will then hold public explanatory sessions to answer questions and facilitate the submission of proposals by smaller organizations and new applicants.

It is important that affected populations have a voice from the beginning in designing and implementing programs that serve them…..

– PEPFAR COP Guidance for 2020, released in 2019.

PEPFAR has learned that there is no better watchdog than people from the community itself once the implementation of an award has started. Clients themselves are usually the best judge of whether a site or a program is doing what it is supposed to; they identify lapses in quality or coverage the fastest.

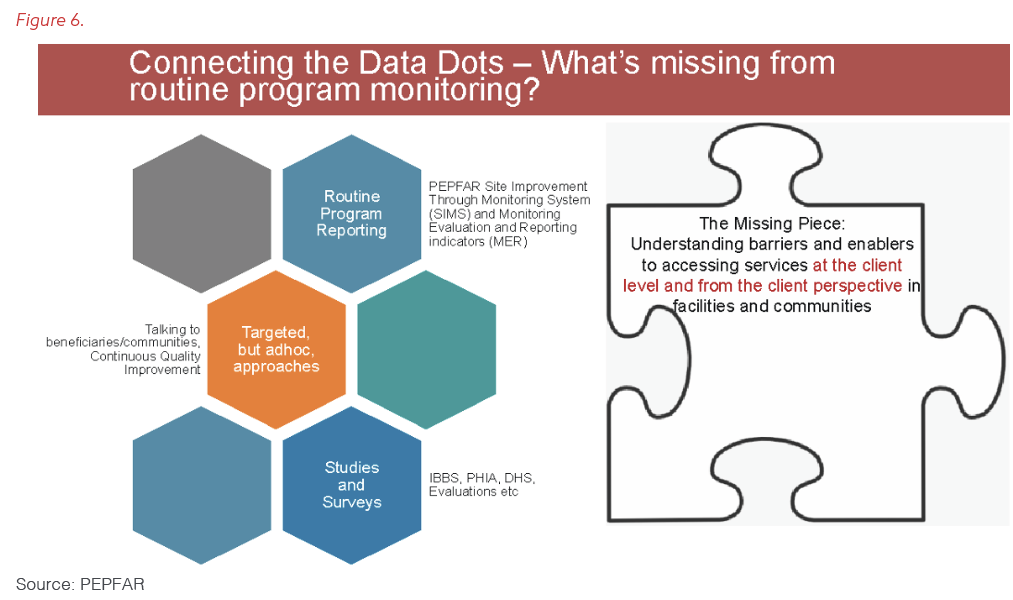

To ensure that every one of its contracts, grants, or cooperative agreements for service delivery is performing to expectations, PEPFAR has adopted a strategy of community-led monitoring. As Figure 6 shows, this approach complements the Site Improvements Through Monitoring System (SIMS) we described in Paper 3 of this series, as well as the Population-Based HIV-Impact Assessments (PHIAs) discussed in Paper 4 and other external evaluations.

Community-led monitoring provides a firsthand perspective from clients themselves on whether partners and individual sites are adhering to quality standards and carrying out policies correctly. Clients and local activists identify if health workers are closing clinics before they are supposed to or not showing up to work at all. They spot shortages of drugs and supplies, as well as breakdowns of essential equipment. They report when staff members refuse services to key populations or present an unwelcoming environment for women or youth. They recommend whether sites should extend their hours, offer more home visits, or make it easier for clients to pick up treatment. They know earlier than anyone else if someone is stealing from a hospital or selling medicines out the back door. In countries with decentralized systems, they advocate for local councils or districts to include financing for health as line items in their budgets or increase the share allocated for health care. In West Africa, reports from community monitors provided the real-world evidence that convinced national governments to eliminate official user fees at public-sector clinics and crack down on illegal charges for services. S/GAC learned from the Global Fund’s experience in this area, especially in West Africa, and invested in expanded direct financial support to ensure the elimination of fees across PEPFAR programs.

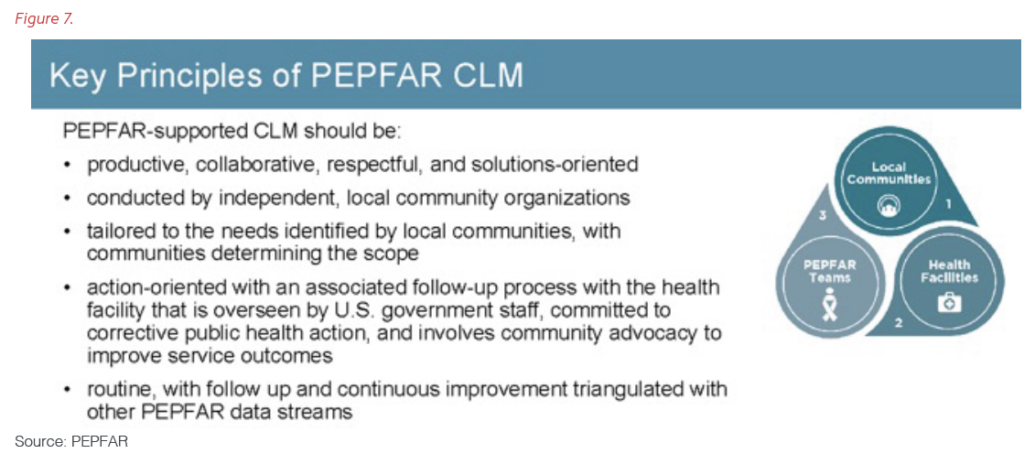

Community-led monitoring improves the accountability and transparency of government and NGOs alike; identifies whether reforms are not reaching the local level; points out legal, policy, and structural barriers that remain; and helps reduce stigma and discrimination, including by health workers. The visits by community monitors and the information they generate do not happen in a vacuum – they connect with PEPFAR’s other oversight and quality-control systems so that the feedback leads to change. Figures 7 and 8 explain the central elements and principles of community-led monitoring.

Community-led monitoring is an essential component of “country ownership” for PEPFAR. Starting with pilots such as the Local Capacity Initiative (LCI) and The Data Collaboratives for Local Impact (DCLI) partnership with the Millennium Challenge Corporation, PEPFAR has created tools that allow clients, health workers, government officials, legislators, and advocates to track and assess the quality and coverage of programs. The community scorecards first introduced by the LCI a decade ago have helped local people improve the accessibility, availability, and compassion of care. Training courses and data laboratories like those established by the DCLI have taught citizens and staff from ministries, CBOs, FBOs, and NGOs to analyze, visualize, and interpret data from sites and surveys. Beginning with the COPs for 2020, each PEPFAR country team has to include funding for this work in its annual budget.

In the world’s hardest-hit nations, HIV/AIDS will be a tragic fact of life for many years to come. The fight against it will succeed today, and be sustainable tomorrow, only if the local population takes ownership.

– PEPFAR Annual Report to Congress for 2006

Summary

For PEPFAR, “country ownership” and “sustainability” translate into two words: “local community.” The more PEPFAR funds local organizations and engages clients and local leaders in the design and implementation of its awards, the greater the chances that people in countries in which the program works will control their HIV epidemics, on their own terms and with their own resources.

PEPFAR’s integrated approach brings together community and government with funders for transparent reviews to design programming that meets the needs of local people. At the same time, it seeks to constantly improve the quality of, and access to, critical treatment and prevention services. Twenty years of data-driven decision-making and careful planning for the 2020 COP in February 2020 created the sustainable platform that preserved access to ART in PEPFAR countries throughout three surges of COVID-19. Proactive policies and the move to local partners ensured PEPFAR’s treatment programs continued even though many international partners could not travel. Clients were able to receive multiple months’ supply of drugs so they did not need to come into clinics simply for refills. This protected clinics and their staff, ensured viral suppression of clients even during the darkest days of the pandemic, and allowed health workers to concentrate on saving the lives of people acutely ill with COVID-19.

In fact, from the beginning, a focus on local ownership has allowed PEPFAR’s programs to continue and even expand during times of crisis. For example, after the many natural disasters and during the periods of civil unrest that have affected Haiti over the last 20 years, local organizations have maintained the provision of ART and even expanded the numbers who receive therapy.

“From the outset PEPFAR worked in partnership with existing US partners and collaborators. …PEPFAR said, “We’re working with the NIH [National Institutes of Health]-funded projects, we’re working with NGOs, and not necessarily directly with government.” So, we were immediately able to start providing antiretroviral treatment to patients in the communities we were undertaking HIV and AIDS research in. … PEPFAR funding enabled us to initiate ARV treatment programs almost immediately.”

– Dr. Quarraisha Abdool Karim, professor in clinical epidemiology at Columbia University, and president of The World Academy of Sciences, in an interview first published by Think Global Health

This is sustainability. PEPFAR has laid the groundwork for the continued evolution of every health and development program to data-driven local management. “Country ownership” for PEPFAR means running programs directly through communities and their organizations, whether public, private, faith-based, or peer led. This ensures all stakeholders are at the table for all aspects of planning, receive direct funding for the delivery of prevention and treatment services, and participate in the monitoring of activities. Some in the development-industrial world promote the idea that “local” means “high risk,” and that more money to smaller foreign entities means more funds diverted. These claims are designed to intimidate and to provide cover for “reforms” that will end up ensuring most funding for “local entities” flows through established, U.S.-based grantees and contractors. Breaking long-established patterns within the Federal Government and with established partners is always difficult, but PEPFAR has shown that a constant focus on the client can make transformative change possible.

PEPFAR has demonstrated that pandemics can be controlled and key elements of health care sustained in a crisis with the active use of data-driven policy reforms combined with funding to peer- and community-led organizations. But the hard work of listening to community voices, recognizing local leaders, and developing and supporting local organizations must take place well before the crisis begins.

The lessons from PEPFAR are relevant for sustainability in all areas of international development. PEPFAR has shown the road map for development is locally owned, sustainable, and has lasting impact.

Recommendations

The United States and other countries and development organizations should learn from PEPFAR’s commitment to engaging local communities and their organizations to improve foreign assistance:

Congress

- Congress should ensure all U.S. Government global health and development programs focus on the direct funding of local nongovernmental organizations.

All U.S. government departments and agencies and other donors that implement foreign assistance related to global health and development:

- The Department of State, USAID, CDC, and other donors should continue active engagement with local communities to plan and implement responses to the current pandemics of HIV, tuberculosis, malaria, and COVD-19.

USAID:

- USAID across all programs should increase its overall target of direct funding to local organizations to 50% by 2028 from 25% currently by using the lessons from localization under PEPFAR.

- USAID should move aggressively to find and fund local and regional private-sector solutions in ordering, warehousing, and delivery to generate greater efficiencies and cost savings in its global health supply chain.

PEPFAR:

- PEPFAR should increase its share of direct funding to local organizations to 90% by 2030 from 70% currently to support achieving the third U.N. sustainable development goal, ensuring health and well-being for all.

- PEPFAR should continue its use of granular local data to ensure programs are reaching everyone in need of prevention and treatment services and only invest in data systems that are transparent and available in real time to local communities and governments.

- PEPFAR should continue funding vehicles that recognize and support implementation science and technical advances and build local capacity through training under technical support agreements with international organizations and the private sector.

Acknowledgements:

The Bush Institute would like to thank Dr. Mark Dybul, former Executive Director of The Global Fund (2013-2017) and former U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator (2006-2009) for his insightful feedback on and review of this paper.