John Bridgeland, CEO of Civic and CEO of the COVID-Collaborative, says that “big citizenship” involves all of us working toward a greater good.

John Bridgeland is the CEO of Civic, a social enterprise firm in Washington, D.C. He also is Co-founder and CEO of the COVID Collaborative and has founded or helped lead organizations that work on advancing democracy, policing and public safety, high school dropout rates, malaria prevention, ocean conservation, and national service. The attorney’s public service includes serving on the White House Domestic Policy Council and at the USA Freedom Corps under President George W. Bush, the White House Council on Community Solutions under President Barack Obama, and as chief-of-staff for then-GOP Rep. Rob Portman of Ohio.

As much of an ideas’ entrepreneur as a social entrepreneur, Bridgeland tapped into his work to discuss the impact of civic engagement with Lindsay Lloyd, the Bradford M. Freeman Director of Human Freedom at the George W. Bush Institute, Chris Walsh, Senior Program Manager in the Human Freedom Initiative at the Bush Institute, and William McKenzie, Senior Editorial Advisor at the Bush Institute. A key takeaway is that “big citizenship” involves all of us working toward a greater good. Shared work, he contends, is a key to civic renewal and civil dialogue.

How do you define civic engagement?

Civic engagement is ordinary Americans doing extraordinary things for the public good. That’s the spirit we want to further awaken in the country, may it be individual acts of compassion, helping a neighbor in need, mentoring a child, or cleaning up a river or park. I got vaccinated today and view that as an act of civic engagement. It’s not just for my own protection, it’s about my family, friends, and community.

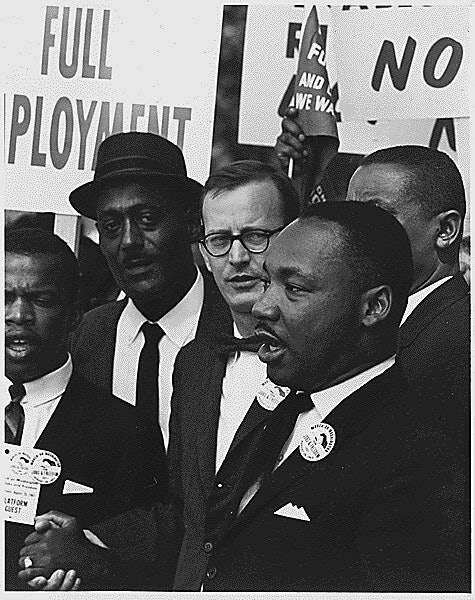

Of course, acts of protest and civil disobedience, if non-violent, are very effective ways to create change. And civic engagement through institutions, such as the family, schools, faith-based groups, nonprofit groups, colleges, and, increasingly, groups of your own formation are forms of civic engagement. Civic engagement can be unnoticed, small acts of compassion. They can be large, public acts that move a nation toward some good.

Civic engagement can be unnoticed, small acts of compassion. They can be large, public acts that move a nation toward some good.

You think of the examples of “Big Citizenship” — Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton leading the women’s rights movement, or Martin Luther King, Jr. leading the civil rights movement. They created their own platforms and moved the country. I also think about the national park system, called “America’s best idea.” That idea began with citizens — like George Catlin and John Muir who cared about these special places. William Henry Jackson films Yellowstone on the Hayden Expedition, and all of a sudden it awakens Congress to create Yellowstone National Park. Citizens were the first movers of this big idea — to put large tracts of land into federal custody for the enjoyment and use of all future generations.

The Peace Corps is another story of civic engagement. Candidate John F. Kennedy asks the 10,000 students at the University of Michigan who waited until 2 a.m. to hear him, “How many of you would be willing to serve your country abroad?” Tens of thousands of students around the country heard that call and got organized, signed a scroll, and sent it to candidate Kennedy. It was a generation of college students that prompted the Peace Corps.

I call this “big citizenship.” It’s why I’m a Republican. I believe in big citizenship more than big government. Those presidents who’ve recognized that spirit of engagement in the American people are often remembered for awakening the best that is within us.

You’ve talked and written about what you call a “civic health challenge.” What do you mean by that term?

When Thomas Jefferson penned that mystical notion of the “pursuit of Happiness” with a capital “H” in the Declaration of Independence, he wasn’t just talking about individual pleasure, a home, or even a good job. He was talking about the public happiness — a cooperative enterprise that we help one another achieve. Democracy works well when we trust and care about each other.

Families, schools, faith-based groups, and civic associations are the enterprises that form our character and moral sense. They are supposed to teach us how to work together across politics, faiths, income levels, race, and ethnicity. But today, these institutions are on the decline and some of the purposes of these institutions are not well understood. And sadly, some of our public platforms, such as the Congress, are really misunderstood — they are viewed now as platforms to promote your own ego or brand.

Our civic health challenge is facing the worrisome trends that Robert Putnam identifies in his new book, The Upswing. He shows that the same trends today — political polarization, lack of social cohesion, economic inequality, and a culture of narcissism — existed in the Gilded Age. He writes that after the turn of the 20th century, those trends moved in virtual lockstep in a positive direction. Unfortunately, those trends started to move in the wrong direction in the mid-1960s to the present day. The result is tremendous inequality, polarization, and a culture of “I” instead of “we.”

Your work with the COVID Collaborative brings together experts, leaders, and institutions to help win the fight against COVID-19. What have you learned about creating a consensus within a diverse group of people and institutions?

In times of national crisis, our national leaders usually spark a sense of civic connectedness and opportunities to help. Tim Shriver and I were alarmed there wasn’t presidential leadership after the pandemic hit our shores in the early part of 2020.

President Bush agreed to record a message to the American people to offer calm, but also to strengthen their resolve. His message went viral on social media and from the New York Times to Fox News. He talked about how we are not partisan combatants, but Americans, and we rise and fall together. And he talked about empathy and finding new ways to connect and serve. It captured the spirit the country needed during this crisis to engage more Americans in their own recovery.

In that context, we organized “A Call to Unite.” We helped raise $100 million from Americans to help frontline healthcare workers and vulnerable populations. We saw there was so much energy in the country that wasn’t being unleashed.

After that experience, I got calls from governors and business leaders asking me to do something more actively on a COVID response. When pandemic meets federalism with 19,000 cities and towns, 3,000 counties, 56 inhabited states and territories, and 326 tribal lands, it’s a recipe for disaster unless you have a full-country response — with institutions, leaders, and individual Americans at all levels playing an active part in the response.

So, I co-founded and now run the COVID Collaborative, which is a national assembly of top experts, leaders, and institutions in health, education, and the economy. My colleague is Gary Edson, with whom I served in the White House. Our co-chairs are Dirk Kempthorne, a conservative Republican who has served as a mayor, governor, senator and Bush Cabinet secretary, and Deval Patrick, a Democrat who has been a governor, a presidential candidate, and a civil rights activist. Members of the COVID Collaborative — which includes a lot of former Bush administration officials — work together across politics to help the response.

This has taught me that Americans are desperate for new models of leadership, where they have platforms for shared work across differences to have public impact.

Can I tell you a Neil Armstrong story?

Sure.

When I was in my early twenties, Neil Armstrong lived down the street in my hometown of Cincinnati. He knew my dad, who treated him as an ordinary guy. At dinner with us, Armstrong said that when President Kennedy issued the challenge to send a man to the moon and return him back safely within a decade, we had no idea how to pull that off technologically. But the call energized 400,000 engineers to collaborate to make it happen. Then, he paused and said, “I don’t understand why we don’t do more of that today.”

I’ve never forgotten that because America is a big country with so much talent and innovation. This gets to the power of civic engagement. We need to do more unleashing of America’s entrepreneurial spirit for the public good. We need a moonshot factory of sorts.

America is a big country with so much talent and innovation. This gets to the power of civic engagement. We need to do more unleashing of America’s entrepreneurial spirit for the public good. We need a moonshot factory of sorts.

Where else do you see civic engagement happening today? And what common characteristics exist in civic engagement today that existed in the past?

The trends I talked about with Putnam are discouraging, but we’re encouraged that literally every week you see a report about some intractable problem, such as chronic and veteran homelessness, actually being solved somewhere in America.

As an example, an entrepreneur in Appalachia said that we ought to approach civic engagement systemically. Working with higher education institutions in West Virginia, he created a kindergarten thru-college social enterprise curriculum.

Imagine being in first or second grade and you learn about how Americans formed our union to those who developed the earliest technologies to those who sparked rural electrification to those who led our civil rights movements to social entrepreneurs who created their own movements. You might say to a young person, “Martin Luther King, Jr. was a kid once — just like you. You, too, can be a social entrepreneur and put your scratch on history!” We have to instill that belief in the potential of every person to make a difference starting at a young age.

Civic engagement can be unnoticed, small acts of compassion. They can be large, public acts that move a nation toward some good.

Let’s talk about the work that you’ve done with America’s youth, especially on the high school dropout challenge. What works and doesn’t work in engaging young people?

The country had data dating back to 1870 on high school graduation rates, but nobody had ever talked to the customer — to the young people who made this extraordinary decision to drop out of high school. We discovered that high school graduation rates had been flattening since the 1970s and more than 1.2 million kids were dropping out every year with tragic consequences to them.

Working with the Gates Foundation, we surveyed students in 25 communities who had dropped out. We published a report, The Silent Epidemic: Perspectives of High School Dropouts. Because it showed these youth had potential and the problem could be fixed — 50 percent of dropouts were found in just 15 percent of high schools — it prompted the TIME cover story, Dropout Nation, Oprah shows, and other national attention – or rather national outrage. People have to get angry sometimes to create real change. This was an emotional experience.

To take just one example, we listened to a young girl in Philadelphia who was so charismatic. She wanted to be an astrophysicist. She said her best day was when she read the “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.” She quoted parts of that letter and related it to her service-learning project in Philadelphia. She said those uplifting days in school were extremely rare.

Unfortunately, for her and many other students, the marketplace of the streets was far more interesting than the marketplace of the school. Kids were bored out of their minds. Later in the interview, when we asked what she was doing now, she said she was a prostitute on the streets of Philadelphia.

How does someone go from wanting to be an astrophysicist to seeing no connection to those passions in school and ending up working the streets? John DiIulio, who had been President Bush’s faith-based czar, worked with me on this project and was in the room when we saw this young woman describe her experience. We said to each other that we were going to do everything in our power to boost high school graduation rates and help young people realize their dreams at some level.

We discovered there wasn’t a common calculation of graduation rates, so we helped 50 governors sign a graduation rate compact, and Margaret Spellings, who was secretary of education, later issued a regulation requiring all states to report that common rate. It was game-changing. Together with clear graduation rate goals set by governors and clear data, including by race, ethnicity, and income, you could chart progress.

What I learned is how often, through government and civil society, we propose to do things to populations without first listening to them. Those students were the keys to informing a “Civic Marshall Plan” based on evidence of what actually worked and that schools, districts, states, nonprofits, and others had embraced. That has led to more than four million more students graduating from high school rather than dropping out. Black and Hispanic students drove gains in graduation rates and have more than doubled their college enrollment rates.

What I learned is how often, through government and civil society, we propose to do things to populations without first listening to them.

Yuval Levin at the American Enterprise Institute talks about the transformative power of principled institutions. What role do you think community institutions play in encouraging greater community engagement?

Yuval’s exactly right. When you think of institutions, it’s the American family, church, school, civic groups, clubs, nonprofit and faith-based organizations, and all the way to the Congress. But, as Yuval has said, we have a misunderstood view of institutions.

We need to understand institutions as places where we form our characters, our moral sense. People don’t like to talk about the moral sense so much anymore, but our values are shaped in these institutions and what we eventually value bubbles up to what our nation values. The lack of such understanding of institutions breeds the chaos we see today.

[National Constitution Center President and CEO] Jeffrey Rosen wrote an Atlantic cover story called “Is Democracy Dying?” His thesis was that civic and religious intermediating institutions that were vibrant 30 years ago are on the decline today. You learned how to participate in your democracy. You learned to respect both majority rule and minority dissent.

I really worry today, for the first time in my lifetime, whether multi-racial, multi-ethnic democracy can actually survive in America.

Institutions are critical to this survival. They can be new, too. They don’t have to be the Rotary Club or the United Way. They can be ones millennials create.

What gives me hope is that surveys show the American people are far more united on how to solve problems than our national politics, media, and Congress reflect. The more energy we can unleash in the country through shared platforms and institutions, the better off we’ll do in terms of solving problems.

Our last concept to talk about is civil dialogue. Where do you see people having civil discussions? What conditions make them possible?

I think we first need more shared work, not words. Shared work often leads to more civil dialogue.

We need to provide more opportunities for shared work, and then talk about the values that brought people to that common enterprise. That will lead us to looking at people, not so much as Republicans or Democrats, rich or poor, or of a particular faith, but as people who share a common humanity.

I was asked to help the interfaith dialogue movement 15 years ago. Karen Hughes from the State Department spoke at our summit about a “diplomacy of deeds.” With some philanthropic support, we organized in 42 hotspots around the world opportunities for people from different faiths — Christianity, Judaism, and Islam — to work together on a tough public problem. After these partnerships were formed, they talked about what was it about their faiths that compelled them to serve. They discovered it was the same Abrahamic tradition.

The COVID Collaborative has worked hard to transcend politics and have an impact. We have officials from the administrations of Presidents Carter, Clinton, Bush, Obama and Trump all working together and the former presidents and first ladies have joined our vaccination education campaign.

Now, neuroscientists tell us that we’re wired to cooperate. When we serve other people, it triggers regions in the brain that make us healthier and happier and more fundamentally connected. People ultimately want that.

We need to provide more opportunities for shared work, and then talk about the values that brought people to that common enterprise. That will lead us to looking at people, not so much as Republicans or Democrats, rich or poor, or of a particular faith, but as people who share a common humanity. When I think this is just some kind of dream, I then see Americans who reflect this diversity working together on a common problem and getting results, and I see that dream realized. That gives me hope for the future.