Central America Prosperity Project: Background Paper

In Session One of the Bush Institute Central America Prosperity Project (CAPP), emerging and experienced leaders from El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala will share insights regarding both progress and hindrances over the past two decades to achieving sustained economic growth in the region. The group will consider pending reforms, potential strategies for emerging leaders, and opportunities to collaborate with key partners in the region and in the United States and, in subsequent sessions, consider how to carry these strategies out.

This background paper provides a brief overview of the central premise for economic growth in Central America – reforms to enable competition and investment in economic sectors, regional economic integration, and engagement in global trade – as well as the underlying structural weaknesses, and political and social developments that are inhibiting stability and growth.

Assessing Progress and Setbacks

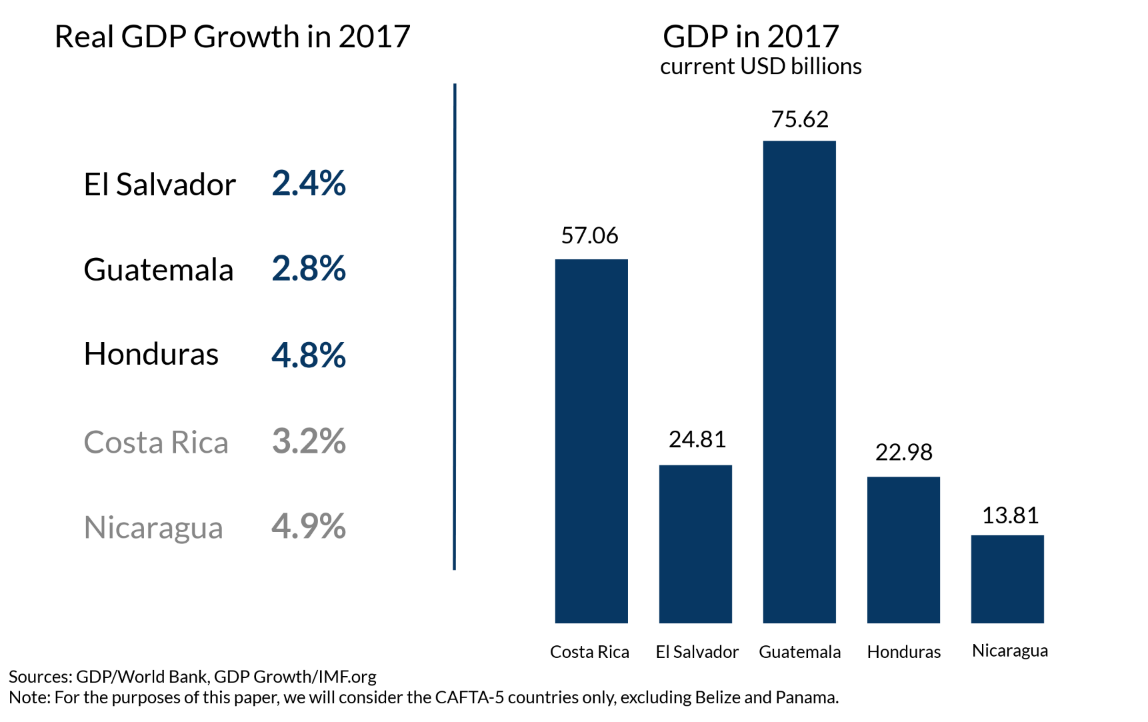

The Northern Triangle countries have implemented important structural reforms and achieved greater openness to global trade over the last two decades, in part through implementation of the US-Central America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA). According to the IMF, the Central American region as a whole, encompassing Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Panama, experienced a weighted average real GDP growth of 3.7 percent in 2017. This rate of growth was close to the global average of 3.8 percent, and faster than the United States, its largest trading partner, which grew at 2.3 percent. Yet Central America’s growth rate belies significant structural obstacles to sustained and inclusive economic prosperity.

GDP per capita remains low, measured in 2017 current international dollars at purchasing power parity as 8,948 in El Salvador, 8,145 in Guatemala, and 5,562 in Honduras; income disparities within the three countries’ populations are significant.[1] Public finances are spread thinly in the effort to offer essential public services and invest adequately in infrastructure. Additional reforms are needed to promote private sector diversification into higher value-added production and services and encourage the mainstreaming of smaller-sized enterprises into the formal economy. Human talent must be invested in as a foundation for broad-based prosperity, while at the same time immediate actions are required to address the severe risk to basic personal safety caused by the organized crime prevalent in the region.

Addressing all of these prerequisites for growth will require the CAPP Working Group to reflect on the overlap between the region’s goals for increased trade and economic growth, and its approaches to security, education and health, trust in public institutions, and transparent governance. Continued deficits in each of these social areas could significantly hamper the ability of the Northern Triangle countries to reach their economic growth potential.

Growth through Free Markets and Regional Integration

The Central American Common Market (CACM) was created in 1961 as the first regional trade agreement in Latin America. Adhering to the industrialization theories of the day, it was constructed to lower barriers to intra-regional trade but maintain high barriers to imports. Hampered by macroeconomic setbacks, political upheavals and civil strife through the 1980s, little progress was made to advance the customs union. Renewed efforts in the 1990s under a more open, market-oriented approach produced deeper integration in areas such as investment promotion, intellectual property protections, and harmonization of technical standards. Important progress was made to harmonize tariffs and reduce internal barriers to trade, exceptions in key products notwithstanding.

[1] The source for GDP per capita data is the IMF World Economic Outlook Database, April 2018. GDP figures are continually updated by national agencies, so IMF accounts may differ from national accounts if the timing of updates is not synchronized.

The U.S.-Central America Free Trade Agreement (formally the US-DR-CAFTA, but herein referred to in shorthand as CAFTA) was constructed to advance the completion of a full customs union and promote regulatory reforms. The political collaboration required to negotiate and implement CAFTA was also directed toward expanding regional financial institutions with common banking standards and regulatory oversight, an initiative that attracted international banks to further develop the region’s capital markets. Institutions such as the Secretariat for Economic Integration in Central America (SIECA) that were critical to supporting CAFTA continue to play a role convening ministerial-level coordination of fiscal and economic policies. The Northern Triangle countries have pledged to facilitate the mobility of workers to increase the efficient use of human resources and potentially reduce emigration out of the region.

CAFTA’s Initial Results and Limitations

CAFTA eliminated tariffs and promoted significant regulatory and legal reforms, including opening sectors previously closed to private investors. In the first ten years after CAFTA’s entry into force in 2006, Central American total trade with the United States increased 17 percent in real terms from $27.9 billion to $32.7 billion annually, with positive spillover effects: Central American trade with the world increased 20 percent.

CAFTA helped position Central American companies to participate more significantly in global value chains, which is a key avenue for companies, particularly in small economies, to continually acquire expertise and knowledge conducive to productivity growth. The increased presence of multinational corporations similarly offered opportunities for domestic firms to adopt new technologies and practices.

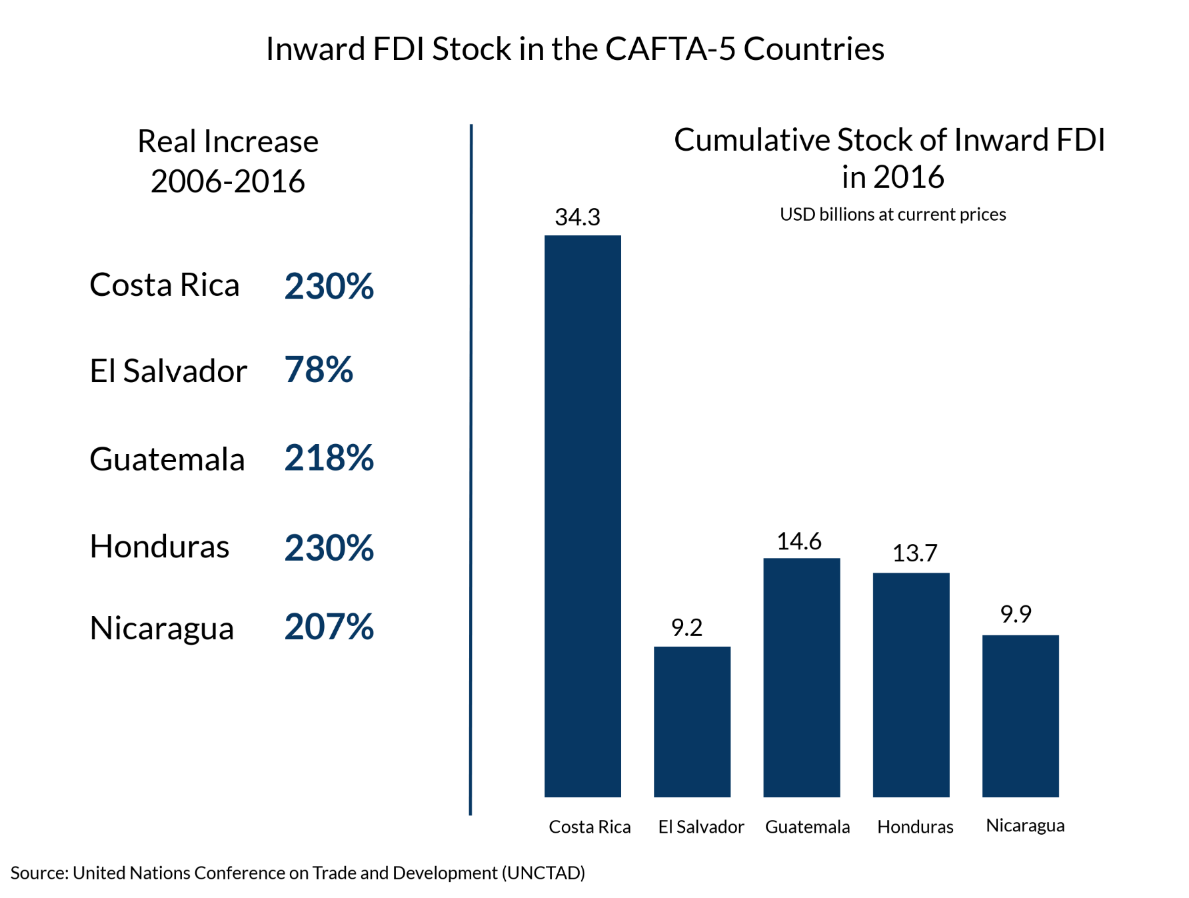

Central America’s current account deficits are primarily financed by remittances and foreign direct investment flows, which help the region overcome low capital formation in general. According to the Plan of the Alliance for Prosperity in the Northern Triangle issued in September 2014, investment in the Northern Triangle was 18 percent of GDP over the decade since 2004, but lags the Latin America average of 21 percent, and the average of 31 percent across medium- and low-income countries. Since the implementation of CAFTA, the value of inward FDI stock in CAFTA countries has increased significantly, by an average of 221 percent in real terms, except for El Salvador. El Salvador’s level of inward FDI increased 78 percent in real terms, perhaps dampened by security risks. The United States and Panama are the largest investors in El Salvador; the United States and Mexico are the two largest investors in Guatemala and Honduras.

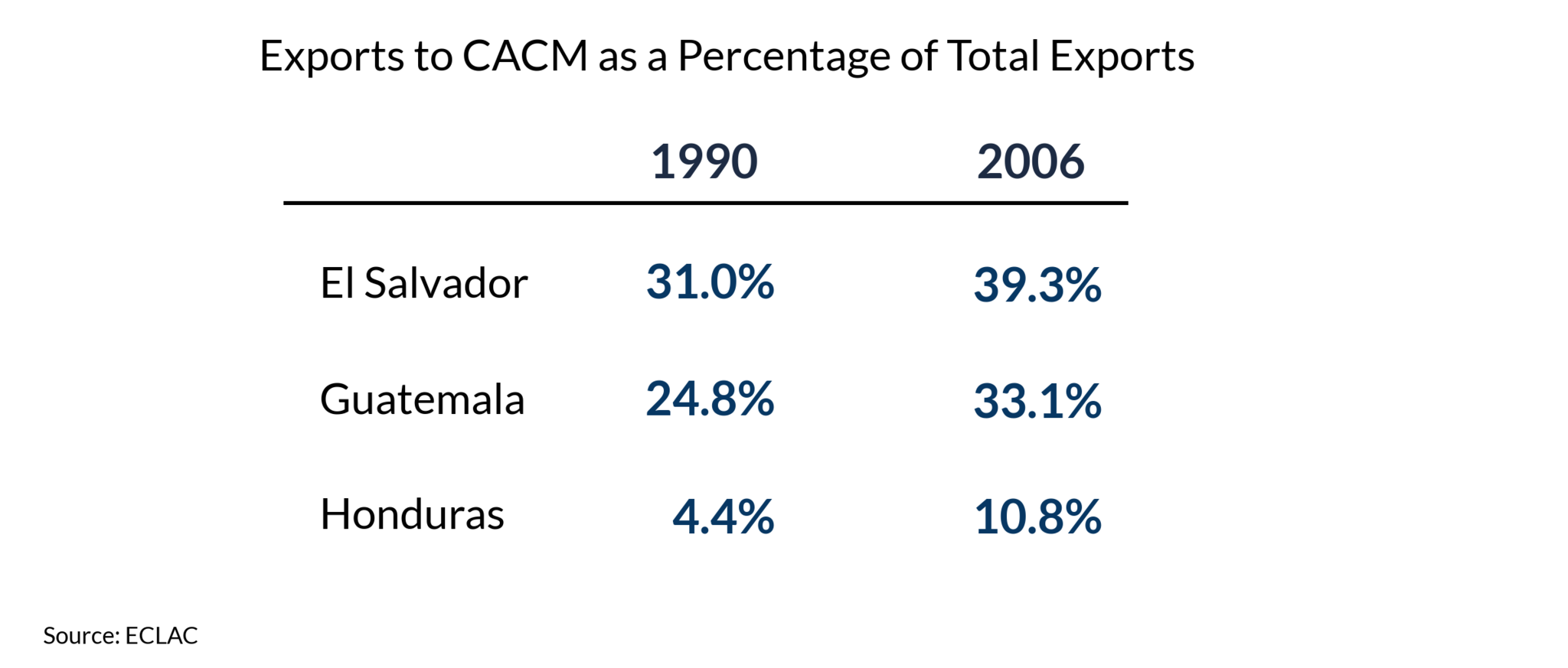

Goods trade among the CAFTA-5 countries, which stood at $5.7 billion annually in 2006, has increased 46 percent in real terms to $8.3 billion annually in 2016. According to SIECA, intra-regional exports increased from 26 percent to 29.5 percent of total exports between 2006 and 2016, while intra-regional imports as a percentage of total imports remained relatively unchanged at 14 percent. The countries within CAFTA do not enjoy the same degree of intra-industry trade and intertwined supply chains that characterize the industrial relationships in North America under NAFTA. Partly, this is caused by remaining cross-border and infrastructure barriers to intraregional trade.

According to the World Bank, efficient physical infrastructure and good intermodal connectivity are important catalysts for development and deeper regional integration. More efficient supply chains can produce poverty reduction outcomes by connecting rural and small producers to nearby markets, creating employment opportunities for the manufacture of traded goods, and reducing the delivered prices of primary goods. At the borders, adopting best practices such as fully electronic and interoperable documentation systems, harmonization of border controls, mutual recognition of sanitary and phytosanitary approvals and certifications, and implementation of authorized economic operator programs and risk systems would all generate efficiency gains, supporting higher GDP growth. In the last year, Guatemala and Honduras have made important gains, reducing the time to cross several entry points by putting into place integrated procedures wherein shippers can file once electronically and have their documents approved rapidly by QR code at the border – an approach that should be adopted widely within the region. The recent announcement that El Salvador would join this burgeoning customs union bodes well for such expansion.

The cost of extra-regional trade is also higher than need be due to the inefficiency of Central American ports, which are relatively small. For example, it costs twice as much to ship a container from Guatemala to Long Beach, California as it does to ship the same container from China. A study by the World Bank suggests that integrating trade infrastructure would not only boost regional trade; the value of intraregional exports, exports to the United States, and to the EU27 could increase as much as 53 percent.

Barriers to Sustained Growth in the Northern Triangle Economies

Lack of Economic Diversification

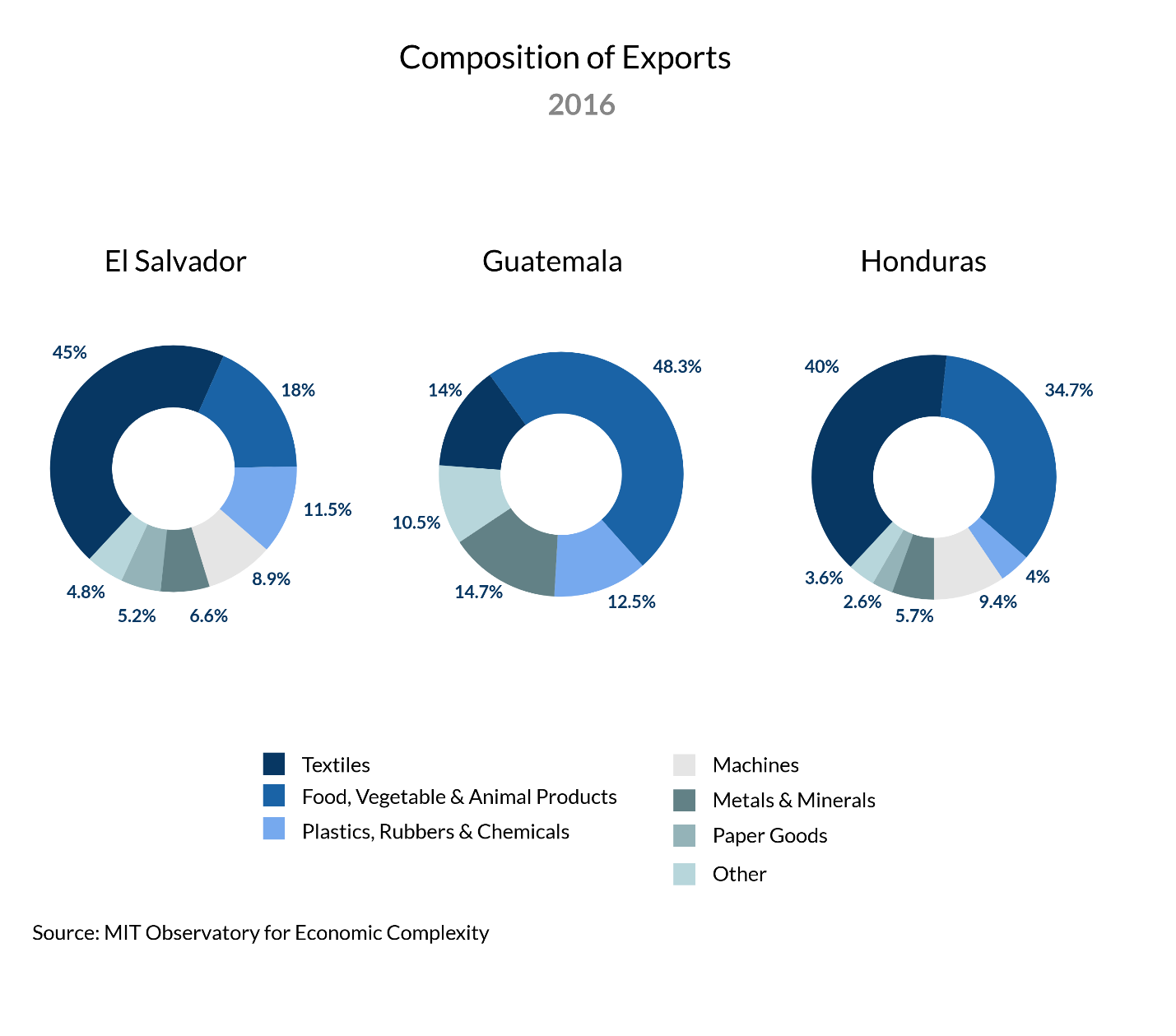

The region is highly integrated in the world economy. Though the dependence on agricultural exports has been significantly reduced, the region’s export portfolio is still comprised mainly of commodities, including agriculture, foodstuffs, textiles, plastics and chemicals, and minerals and metals. Agriculture only drives 5.8 percent, 10 percent, and 12.9 percent of the value added to the economies of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras respectively, yet 18.8 percent, 29.4 percent, and 28.5 percent of workers are employed in agriculture in each country.

Although commodity prices have been favorable for Central American trade, lack of diversification means the region remains exposed to price fluctuations – it is a price taker for exported commodities such as coffee and sugar as well as for its key imported commodities such as hydrocarbons. The United States is by far each of the Northern Triangle countries’ largest export market, receiving 46 percent of El Salvador’s exports, 34 percent of Guatemala’s exports, and 35 percent of Honduras’ exports.

Underinvestment in Infrastructure

Beyond addressing remaining customs inefficiencies, the Northern Triangle countries need to expand the coverage and improve the quality of all aspects of intermodal transportation, from roads and railways to ports and airports, focusing on projects that strengthen regional integration and including secondary and tertiary networks. Currently, less than 2 percent of GDP is dedicated to physical infrastructure. Greater access to long-term capital finance as well as incentives to attract private investment are needed to help pay for infrastructure upgrades.

Liberalization in energy and telecommunications has attracted private investment and reduced the cost of these critical inputs, helping to support the competitiveness of firms throughout the economy. Liberalizing and encouraging greater trade and investment in soft infrastructure such as legal, accounting, engineering, and other professional “backbone” services would promote trade in high-value services within the region and benefit producers who require these services.

The Large, Persistent Informal Economy

Poverty in the Northern Triangle remains high, hampered in large part by a lack of formal employment opportunities. According to the World Bank, the percentage of the population at the national poverty line in 2016 was 38.2 percent in El Salvador, 59.3 percent in Guatemala, and 60.9 percent in Honduras. Though formal unemployment is relatively low at just 3.6 percent in 2016, employment in the informal sector is extremely high in the Northern Triangle according to World Development Indicators: 71 percent in El Salvador, 84 percent in Honduras, and 81 percent in Guatemala, compared for example to Costa Rica, where employment in the informal sector is only around 31 percent. Informality has implications for these countries’ tax base as well as for individual workers who cannot reinvest in their families’ education and health, and who do not always enjoy basic labor protections themselves.

Youth employment is a critical focus for the region. Less than half of 20-24-year-olds have a high school degree. In Guatemala, only 33 percent graduate from a secondary school. While completion of primary school is high, Central American countries are low performers in standardized reading and mathematics tests. More than one million young people in the region are at risk because they are neither employed nor in school. Gang infiltration of schools and fear for personal safety are leading factors behind El Salvador’s growing school dropout rate. El Salvador’s Ministry of Education reported that only 42.6 percent of students who were in sixth grade in 2011 were still in school in 2016. Among the goals of the Plan of the Alliance for Prosperity is the creation of job centers in high-risk neighborhoods and the establishment of an education investment plan focusing on primary, secondary, and vocational schools.

Raising productivity growth in the region depends on diversification into services sectors that may require particular skill sets, including the ability to innovate and adopt new technologies. Improvements in public education and workforce development are critical to position the region to attract investments and job creation in the formal economy and to position the region’s workers for better jobs, so they can earn more, save more, and invest in their family’s health and education.

Insufficient Revenue Base

The income and corporate tax bases in the Northern Triangle are not broad enough to fund core government operations and dedicate the necessary resources to fight and prosecute crime, build infrastructure, deliver basic public services such as power and water, and improve public schools to promote greater educational attainment. In 2015, the total income and corporate tax revenue to GDP ratios were 3.6, 5.7, and 6.7 percent in Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador, respectively, compared with an average 5.8 percent in Latin America[2]. Central America relies more on indirect taxes (such as value added taxes) for revenue, which can be regressive in impact.

The total net tax revenue to GDP ratios in 2015 10.2, 18.1, and 16.9 percent for Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador, respectively; the average for Latin America was 15.8 percent. The large informal sector both erodes the tax base and creates a challenge for tax administrators to enforce existing tax legislation. Merely improving corporate tax collection would be insufficient, however; more businesses would need to be encouraged to shift into the formal economy with lower rates and reassurances of pro-market regulatory and legal reforms. Further widening the tax base would be politically challenging; the citizenry would need to be convinced that competent authorities are adhering to transparent and accountable budgeting processes, avoiding corruption and cronyism. Legitimate businesses are already under severe financial strain from persistent extortion from illicit actors, such as gangs.

Social Instability, Risks to Personal Safety, and Migration

Low educational attainment rates, poor access to basic services such as healthcare, and fear for personal safety are all sources of social and economic fragility in the region that require the attention of emerging leaders.

In El Salvador, where gang-related violence is highest, there are thought to be twice as many gang members as active duty armed forces and National Civil Police officers combined, creating enormous strain on youth in particular who are susceptible to forcible gang recruitment. Over 150,000 homicides have occurred since 2006, a murder rate that is five times higher than the occurrence rate considered an epidemic by the World Health Organization.

Personal and economic insecurity, along with a desire for family reunification, underlies the steep increase in migration. According to the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, 350,000 people from the Northern Triangle filed for asylum worldwide between 2011 and 2017. More than one-third—130,500—applied in 2017. Over this same period, the United States experienced a 1,089 percent increase in asylum applications from Salvadorans, Hondurans, and Guatemalans.

High levels of migration threaten to undermine future investments in a skilled workforce. Less visible outside the region is the so-called “silent emergency” of internal displacement as families flee their communities to escape violence. In Honduras, a study in 2013 conducted by an inter-institutional commission estimated some 174,000 Hondurans have been internally displaced due to violence.

At the same time, the United States deported 304,196 individuals back to the Northern Triangle region between FY2013 and FY2015, most of them on criminal grounds, though Homeland Security has not provided a specific breakdown of criminal versus noncriminal deportations. All three countries lack resources for reintegrating deportees and have expressed concern that gang members quickly secure a strong foothold engaging in drug trade and other illicit activities upon returning to the region.

In an attempt to remedy this cycle of domestic violence and immigration, the United States launched the Central America Regional Security Initiative (CARSI) in 2008 to strengthen law enforcement capacity and judicial systems in the region, spending nearly $1.2 billion between FY2008 and FY2015. About 56 percent of this money was allocated to the Northern Triangle. Though limited in size and scope, the program has helped support some homegrown programs such as El Salvador Seguro, which has reduced homicides by 30 percent on average across 10 high-risk municipalities in El Salvador. As such, the program may provide insights and a foundation on which emerging leaders can build.

Political Instability and Lack of Institutional Capacity

Emerging leaders have the challenge of working to improve the professionalism and capacity of the region’s institutions of governance. Facing a deficit of public trust in the wake of high-profile and persistent cases of corruption, genuine reforms should attempt to instill civic institutions with independence, skills, transparent decision-making processes, and clear, relevant mandates to foster pro-market, competitive conditions while reliably providing basic social services. Currently, each of the Northern Triangle countries scores low on the Heritage Foundation Index of World Freedom “Government Integrity” indicator and the World Economic Forum Global Competitiveness Index “Institutions” indicator. Further, while Freedom House’s 2018 Freedom in the World report rates El Salvador as “Free,” both Guatemala and Honduras receive a “Partly Free” rating and all three countries are described as having serious problems with corruption and lack of confidence in institutions.

The Alliance for Prosperity is a symbol of political will and there are bright spots among officials such as the region’s attorneys general and prosecutors within newly formed anti-corruption agencies, who are showing leadership in cleaning up and strengthening the judicial systems in each country. Their successes with intelligence-based policing and forensic financial investigations, which led to significant legal actions against organized crime are helping to build confidence among citizens and legitimate private sector actors. However, these successes must be safeguarded and multiplied through continued support. Beyond the criminal system, improved enforcement of commercial contracts and the ability to adjudicate in the courts are critical to attracting high-quality investments in the region.

Persistent Threats of Natural Disaster

Central America has suffered more than 50,000 deaths and the displacement of over 10 million people across the entirety of the region due to hurricanes, earthquakes, floods, and volcanoes in recent years. In addition to the societal toll, repeated natural disasters take an economic toll. ECLAC reports that the recent eruption of the Fuego Volcano in Guatemala had an economic impact of US$220 million. Most significantly, the cumulative economic effect over time represents between 5 and 20 percent of government expenditure, according to Fitch Ratings. Greater accumulation of reserves would enable the region’s governments to prepare for, respond to, and recover from the negative shock of disasters.

Prioritizing Policy Reforms and Investments

While the CAPP Working Group will collaborate to identify “next generation” reforms, emerging leaders must also consider how to prioritize reforms that will have the most impact on growth of the Northern Triangle region and quality of life for its citizens. Once prioritized, they can delve deeper into policies, actions, and partnerships necessary to achieve them.

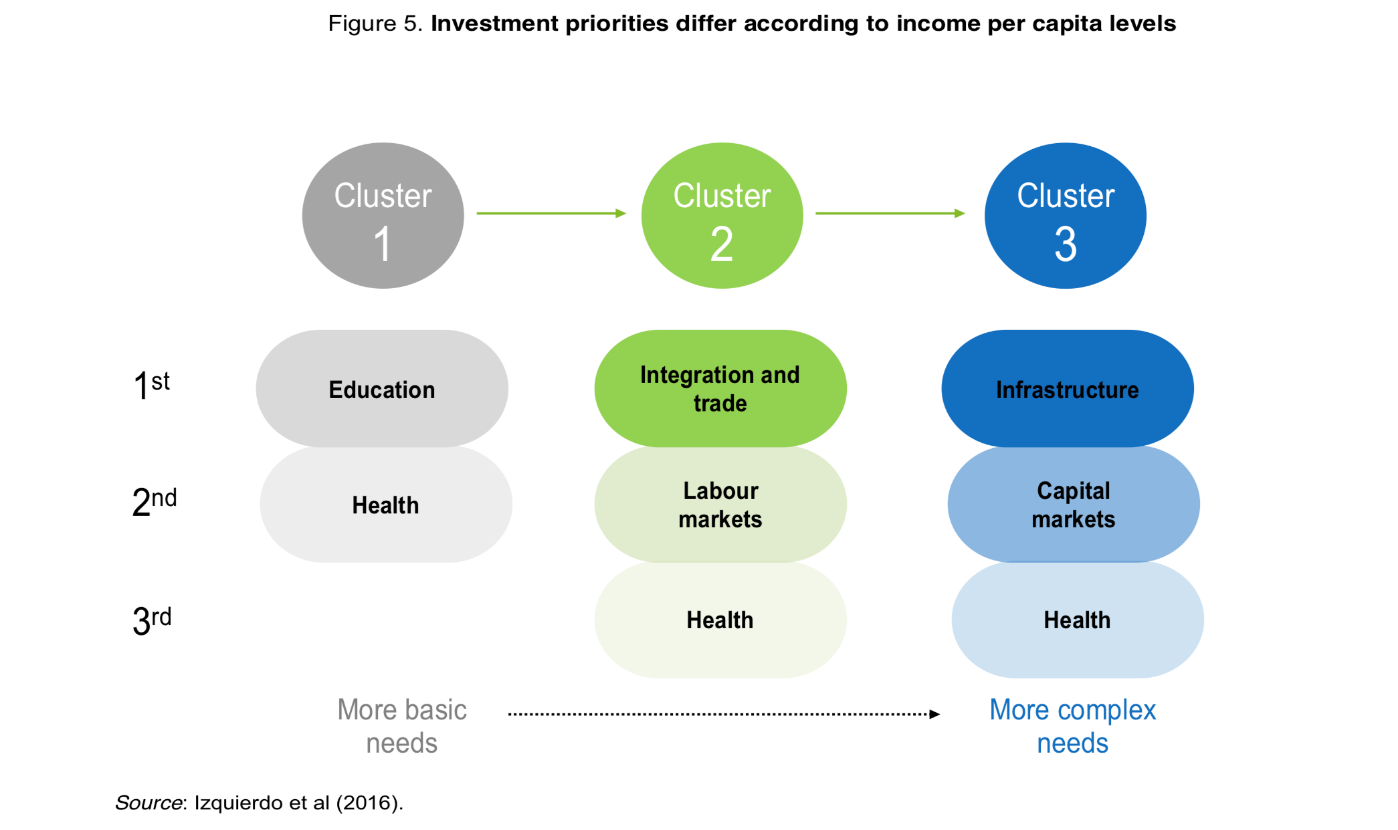

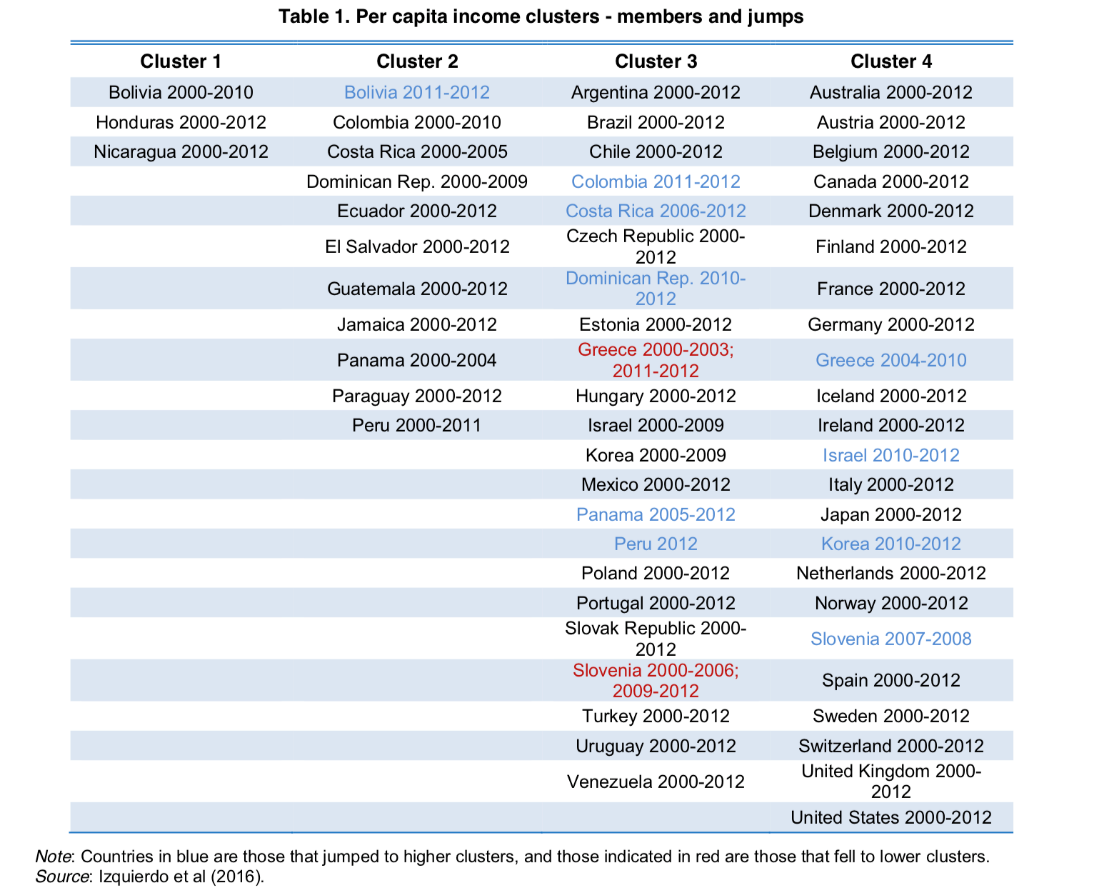

The OECD in collaboration with the IDB, analyzed the development pathways of countries in Latin America. The authors found commonalities and identified policy investments that were most relevant and effective at improving productivity and competitiveness for countries at varying income levels for improving productivity and inclusiveness.

[2] Inter-American Center for Tax Administrators IDB-CIAT Revenue Collection Data Base. El Salvador´s ratio adjusted with new GDP figures.

By targeting these priority areas, countries such as Bolivia, Peru, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic and Panama have been able to make the leap to higher income clusters.

Honduras was categorized in “Cluster 1”; despite significant improvements between 2000-2012, Honduras did not make the jump to Cluster 2. El Salvador and Guatemala started and remained in Cluster 2. Utilizing this framework for guidance, emerging leaders in the Northern Triangle countries may wish to focus on investments in education, health, trade and investment integration, and strengthening of the labor market as the basis for propelling their countries to the next level.

Regional vs. National Interests

In addition to prioritizing types of reforms, the region’s leaders will need to decide whether and how to jointly invest in strengthening regional infrastructure, harmonizing regulation, and developing regional financing. Are there criteria for determining which projects should be politically and socially targeted for a specific country and which would be more impactful and feasible if approached as a region? What is the right role at this time for the United States in supporting regional priorities, and how should Central American leaders engage the U.S. Government and other U.S. organizations on a shared agenda?