Strengthening Community Bonds Two Centuries after De Tocqueville

The Great Experiment – American democracy – depends on the lessons learned in neighborhoods and within families. How can leaders ensure that policy strengthens communities?

Almost two hundred years ago, political theorist and sociologist Alexis de Tocqueville traveled throughout the United States seeking to discover what made democracy work here when it had failed in other places (most notably his native France). One of Tocqueville’s key observations in his famous Democracy in America was that Americans exhibited remarkably robust institutions and instincts for civil society—strong neighborhoods, communities, churches, clubs, etc.—and that this strength provided vital support for the health of the democratic polity.

In some ways, this strength endures. Americans give far more money, as a share of GDP, to support charitable and community organizations than do people in other countries. We give more than twice as much, as a percentage of GDP, to charitable and civic causes as people in Britain or Canada. We give more than seven times as much as people in France or Germany. Americans are also relatively generous in volunteering their time. This collective generosity spawns community action and often unheralded leadership across the country.

The decline of the civil society

At the same time, however, the fabric of American civil society is unquestionably fraying. Robert Putnam, in his book Bowling Alone, famously sounded the alarm 15 years ago, documenting declining American participation in organizations from churches to Rotary Clubs, Boy Scouts to bowling leagues. This declining social participation, Putnam argued, eroded the civic “glue” holding America together, decreasing the range of people’s human relationships and attenuating their sense of connectedness to their communities.

Since the publication of Putnam’s book, the situation has deteriorated considerably. Not only have declines continued (and often accelerated) for all of the institutions that Putnam identifies, but cynicism and indifference have manifested themselves in other areas as well.

Neither major political party is trusted or viewed favorably by anywhere close to half the American electorate. Surveys show declining public confidence in a range of institutions, including those often seen as “conservative” (law enforcement, churches, corporations) and “liberal” (the media, higher education, labor unions).

Advances in information and communications technology have, ironically, made it progressively easier for people to disengage from their communities, substituting quick, superficial, “virtual” interactions for more deeply textured ones. Moreover, all of these tendencies are most pronounced among younger Americans, suggesting that the trends are likely to accelerate, rather than stabilize, over time.

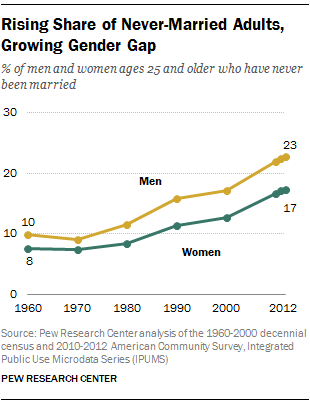

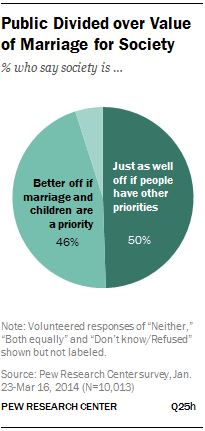

Most troublingly, data increasingly indicate that the fundamental building block of civil society and human community — the family — is under serious pressure in America as well. Marriage rates have declined significantly, especially among less affluent Americans, and the families that do form are getting smaller. As pollster Stan Greenberg wrote recently in The Guardian: “Millennials are…marrying later and having few children, while working class women are avoiding marriage with working class men who are no longer assured of secure, decent-paying manufacturing jobs.”

From a broad social standpoint, this shift is more than a little disquieting. It is in families that we develop (imperfectly, to be sure) the most basic skills of social cooperation and conflict resolution. In our interactions with spouses, parents, children, and siblings, we are forced to hone the arts of compromise, commitment, and subordination of self so vital to true public-spiritedness.

As more people spend more of their lives outside family settings, we may reasonably expect these virtues to wane. Moreover, the deterioration of family life will inevitably reinforce pressures on the broader civic institutions that Putnam talks about, since it is so often our spouses and children who draw us into various forms of community engagement.

The role of public policy

While all of this is troubling, one might legitimately ask why it poses a specifically political, as opposed to more generally social, problem. The answer lies in the vital mediating role that civil society plays between the individual and the state.

As both Tocqueville and Putnam suggest, civic institutions—neighborhoods, churches, clubs, extended families — provide critical arenas for problem-solving, negotiation, and collective action. As they dwindle and come under increasing stress, we are increasingly left with two starkly polarized alternatives: the isolated individual and the leviathan state.

If social institutions lack the membership, resources, and influence to help those in need and to address local problems, we are forced to choose between a radically indifferent hyper-individualism and an ever-expanding bureaucratized welfare state — two equally unpalatable options.

If social institutions lack the membership, resources, and influence to help those in need and to address local problems, we are forced to choose between a radically indifferent hyper-individualism and an ever-expanding bureaucratized welfare state — two equally unpalatable options.

There is tremendous value in having robust social organizations that can provide resources for their members and help for those in need, and in having citizens who feel meaningfully connected to institutions and ideals bigger than themselves. A helping hand from neighbors creates civic goods far beyond anything that a check from a government bureaucracy can provide.

No less a figure than Pope Francis — hardly an advocate of the minimalist state — has often stressed this critical social and human dimension of charity.

The key, he urges, is “first to meet, and after meeting, to help. We need to know how to meet. We need to build, to create, to construct a culture of encounter.” He then pointedly asks his audience: “When you give alms, do you look in the eyes of the people you give them to?”

The key, he urges, is “first to meet, and after meeting, to help. We need to know how to meet. We need to build, to create, to construct a culture of encounter.” He then pointedly asks his audience: “When you give alms, do you look in the eyes of the people you give them to?”

William Burchett (right), Troop 584 Life Scout from Holladay, Utah, hands out winter boots to veterans at the annual Stand Down event held at the George E. Wahlen Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Salt Lake City, Utah, Nov. 2, 2012. (U.S. Air Force photo by Staff Sgt. Julianne M. Showalter/ Released)

William Burchett (right), Troop 584 Life Scout from Holladay, Utah, hands out winter boots to veterans at the annual Stand Down event held at the George E. Wahlen Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Salt Lake City, Utah, Nov. 2, 2012. (U.S. Air Force photo by Staff Sgt. Julianne M. Showalter/ Released)

While the Pope’s remarks are clearly rooted in his Christian theology, they have profound implications for the broader civil community. The institutions of civil society, which draw people together and provide platforms and resources for community action, are ideally suited for creating a “culture of encounter.” A Boy Scout troop or church group that serves food at a soup kitchen creates so many more social benefits than an EBT card.

The skills of organization, cooperation, and responsibility developed within the serving organization, as well as the human connections formed between the givers and the recipients, contribute powerfully to robust democratic communities. This is something that neither social Darwinian indifference to the poor nor impersonal, state-coerced wealth transfers can do. One need not advocate the abolition of government welfare programs, nor naively exaggerate the transformative power of occasional volunteering, to recognize this essential truth.

Lessons from successful programs

So if civil society in America is simultaneously so vital and so threatened, what can we reasonably expect policymakers to do about it? We must acknowledge that there is no quick fix or “magic bullet.” Efforts to preserve and revitalize American civic institutions, from families to churches to PTAs, face powerful technological, economic, and cultural headwinds that blow in the seemingly opposite, but actually reinforcing, directions of individual isolation and state expansion. Tocqueville’s vaunted civil society is thus simultaneously squeezed from above and sapped from below.

As leaders develop policies in a whole host of areas, from taxation to spending to regulation, they can and should ask whether the proposals are likely to strengthen or weaken social institutions, to promote or to undermine individuals’ connections and commitments to civil society.

As leaders develop policies in a whole host of areas, from taxation to spending to regulation, they can and should ask whether the proposals are likely to strengthen or weaken social institutions, to promote or to undermine individuals’ connections and commitments to civil society.

The policies that strengthen civil society and a sense of community often cost money, and will not always be the most “efficient” approaches to problems; they do, however, pay great social dividends in the long run.

At the national level, President Bill Clinton’s AmeriCorps program, which provides modest stipends and educational grants in exchange for community service, has helped to motivate and support hundreds of thousands of people in engaging community problems. Likewise, President George W. Bush’s Office of Faith-based and Community Initiatives has facilitated government partnerships with houses of worship throughout the country to provide services to the poor and to address local needs.

Crucially, both of these programs rely on the sort of personal, human contacts and community engagement that are the essential building blocks of healthy civil society, rather than simply sending out federal government checks. Both have also been deemed sufficiently worthwhile to be continued by subsequent presidents of different political parties.

Such community-strengthening policies need not originate in Washington; they can also be implemented by local leaders who think seriously about building and sustaining community. Whatever one may think of his tenure overall, former Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley provides a good example in this regard.

During his administration, which ended in 2011, he put a major emphasis on building and renovating public libraries, constructing almost 60 new ones and expanding services at dozens of others. This project went against the grain in an era when many have predicted the gradual demise of physical libraries and noted the cost savings available through digital distribution of information. But what Mayor Daley realized was that libraries are not just places to check out books; rather, they could be multi-purpose neighborhood anchors that become foci for human interactions and community engagement.

Mayor Daley’s library initiative is but one example of the kinds of things that mayors around the country are doing to reinvigorate civil society in their cities. While these efforts often fly below the radar screen, they are important contributions to the health of American civil society. Alexis de Tocqueville would definitely approve. With strong local and community leadership, efforts like these can help America address domestic challenges over the next four years.

The Catalyst believes that ideas matter. We aim to stimulate debate on the most important issues of the day, featuring a range of arguments that are constructive, high-minded, and share our core values of freedom, opportunity, accountability, and compassion. To that end, we seek out ideas that may challenge us, and the authors’ views presented here are their own; The Catalyst does not endorse any particular policy, politician, or party.