Listening to Washington, Smith, and Friedman: The Moral Case Against Public Debt

Benefiting from outsized government spending at the expense of future generations isn’t just an economic issue — it’s a moral one.

George Washington in 1787

George Washington in 1787

In his 1796 Farewell Address, President George Washington warned members of Congress to avoid the accumulation of public debt. We should instead, he said, “cherish public credit.” Washington continued:

“One method of preserving it is to use it as sparingly as possible, avoiding occasions of expense by cultivating peace, but remembering also that timely disbursements to prepare for danger frequently prevent much greater disbursements to repel it, avoiding likewise the accumulation of debt, not only by shunning occasions of expense, but by vigorous exertion in time of peace to discharge the debts which unavoidable wars may have occasioned, not ungenerously throwing upon posterity the burden which we ourselves ought to bear.”

For Washington, this was as much a moral mandate as an economic one. A large debt would make it more difficult for the country, just as it does for a household, to call upon the reserves necessary in times of emergency.

More worrying than that, however, was what Washington saw as the immorality of “throwing upon posterity the burden which we ourselves ought to bear.” Why was that immoral? Because it constituted a form of, to coin a phrase, taxation without representation — and a particularly egregious form at that, because our posterity are not yet even alive to voice their opinion.

Because it constituted a form of, to coin a phrase, taxation without representation — and a particularly egregious form at that, because our posterity are not yet even alive to voice their opinion.

The staggering size of our debt

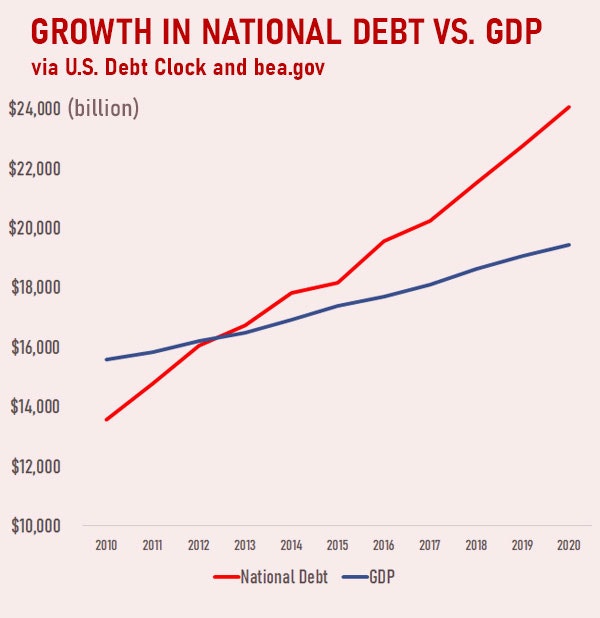

As of this writing, the national debt of the United States federal government has surpassed $23 trillion, which is higher than its current annual gross domestic product (approximately $21.5 trillion), and is climbing rapidly. As large as that number is, it does not include so-called off-budget obligations like Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid.

If we add to our national debt the estimated costs to which we have committed ourselves for those programs, our total indebtedness rises considerably. Estimates vary — necessarily so, because they depend on projections regarding how long people will live, how many of them will avail themselves of these programs, and so on. But educated guesses range from $70 trillion on the low end to as high as an almost incomprehensible $222 trillion.

To give some perspective, that means that our total obligations are equivalent to between three and ten times the current total domestic product of the entire United States.

The federal government’s 2020 budget projects $4.746 trillion in spending, the most it has ever spent, and it anticipates a deficit of $1.1 trillion, which will be added to our national debt. Of that $4.746 trillion, some $2.8 trillion, or about 60 percent, is dedicated to “entitlements,” which includes Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid.

Another $479 billion, or about 10 percent of the budget, will be spent on paying interest on our debt, which is now the fastest-growing part of our budget expenditures. And spending on the military will be approximately $989 billion, about 21 percent of the overall budget.

Put aside for the moment whether these are good, or even necessary, things to spend money on, and consider just the total amount of debt it represents: Every man, woman, and child in the United States today faces an individual personal share of $61,151 of America’s current national debt.

If we add the United States’ current unfunded liabilities, then each individual’s share, as of this writing, rises to a range of between $212,121 and $627,727 — and that is assuming we add no more programs and add no more entitlements. A child born in America today is thus immediately, before she takes even her first breath, saddled with hundreds of thousands of dollars in other people’s debt.

A child born in America today is thus immediately, before she takes even her first breath, saddled with hundreds of thousands of dollars in other people’s debt.

Paying off this oversized sum

How exactly will it be paid? How indeed. The federal government does not generate its own wealth, after all: All its resources are taken from taxpayers — those engaging in productive and cooperative wealth creation.

But current taxpayers are not the only ones who will pay. Our children and future generations will pay for it as well. Indeed, it will be future generations who will bear most of our debt. That means that we today who are benefiting from these expenditures are in fact benefiting at the expense of those future generations.

This constitutes a massive wealth transfer from those too young to vote (or not yet alive to vote) to beneficiaries today — that is, to us. And it would seem a clear example of what we might call extraction: the appropriation of benefit for one party at the involuntary expense of another party. Not only have those future generations not voluntarily consented, they have not even been asked.

We can certainly see who benefits from these programs: the current beneficiaries, the politicians who enhance their election chances by promising us benefits, and of course the hundreds of thousands of government officials and employees who administer the bureaus, agencies, and offices. But those who will be required to pay these ever-increasing levels of spending and promising are the future generations — who, unfortunately for them, are unseen and so unheeded.

In his 1776 Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith warned of the “juggling trick” that governments would be tempted to use to provide benefits to people now at the expense of other people later. By issuing debt that would be paid in the future, politicians can offer voters today benefits that seem costless because today’s voters are not asked to pay for them, at least not now.

But they are not costless. They are quite expensive indeed. And if citizens today do not think too hard, or at all, about their children and grandchildren who will have to pay those costs, we can perhaps convince ourselves that no one is harmed.

Perhaps we indulge a sense of political alchemy whereby we come to think that if the government provides something, it is costless. Consider recent proposals for “free” college, “free” healthcare, and so on. These goods and services, however, are not and cannot be free: they require time, money, labor, and skill to produce. If we do not charge the user or consumer for them, that does not mean they are costless; it just means that we are imposing the costs on others.

It can be tempting to want to benefit at others’ expense, especially when we do not know those others, when do not have to look them in the eye, or when they do not yet exist. But all goods and services, and all wealth, must come from somewhere, and it must be produced by human beings and through human action. Even if we expropriated 100 percent of the wealth of all of America’s 607 billionaires, that would amount to approximately $3.5 trillion, or only about 15 percent of current national debt. Where would we get the rest? As Milton Friedman liked to say, there is no such thing as a free lunch. Alas.

The moral question

Consider, however, the moral principle involved. If a principal reason to address climate change now is because it is immoral and wrong to impose costs and diminished prospects on future generations, then the same moral principle applies to our debt: It is wrong to impose harms or costs on unwilling others, including future others. If we wish to have something, we should pay for or provide it ourselves.

If a principal reason to address climate change now is because it is immoral and wrong to impose costs and diminished prospects on future generations, then the same moral principle applies to our debt: It is wrong to impose harms or costs on unwilling others, including future others.

If we take on debt, we should ourselves be responsible for paying it off. Voluntarily taking on debt is, after all, making a promise that we will pay the money back, and when others loan us their money, they trust and rely on us to keep our word. There are few moral rules more important than keeping one’s word when one gives it.

When, by contrast, the government issues debt to pay for goods, services, and programs, it promises to pay that debt off at someone else’s expense. It is not the case, after all, that politicians will pay for their promises and programs themselves; instead, they are obligating others — other taxpayers and future generations — to pay it.

Because the cost is distributed across millions of people, however, or especially if it is distributed across millions of not-yet-existing people, it may appear, by Smith’s “juggling trick,” as though it is costless and as though the benefits provided are “free.” But they are not free, they are not costless, and our rising tsunami of debt risks not only diminishing our own future wealth and opportunities but also the freedom, opportunity, and prosperity of future generations.

The United States has in its history created more wealth in real terms than any other country in the history of the world. Yet it has now also created more real debt than any other country in the history of the world. At some point, there will be a reckoning. And every day we wait to address our debt, the problem only gets worse.

It is we who have created this problem, however, and so, as Washington said, it is a “burden which we ourselves ought to bear.” Otherwise, we will leave our children encumbered by the crush of our own irresponsibility. Our children deserve better than that.

The United States has in its history created more wealth in real terms than any other country in the history of the world. Yet it has now also created more real debt than any other country in the history of the world. At some point, there will be a reckoning.

The Catalyst believes that ideas matter. We aim to stimulate debate on the most important issues of the day, featuring a range of arguments that are constructive, high-minded, and share our core values of freedom, opportunity, accountability, and compassion. To that end, we seek out ideas that may challenge us, and the authors’ views presented here are their own; The Catalyst does not endorse any particular policy, politician, or party.

-

Previous Article How Would You Balance the Budget? An Essay and Reader Quiz by Robert Bixby, Executive Director of the Concord Coalition

-

Next Article Debt Lessons from the States: Investing in Public Employees while Protecting Taxpayers An Essay by Margaret Spellings, President and CEO of Texas 2036 and Former Secretary of Education