How Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security are Driving the National Debt — and How We Can Fix It

As medical costs increase and our population grows older, the stresses placed on the U.S. budget are projected to continue to increase. How can Congress best address the situation before the debt begins to cause a true crisis?

Maya MacGuineas discusses the federal budget on C-SPAN before the 2016 election.

Maya MacGuineas discusses the federal budget on C-SPAN before the 2016 election.

Maya MacGuineas is a warrior for stewardship. In her case, stewardship of America’s fiscal resources. As president of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, MacGuineas leads an organization that helps analyze and develop policies to control deficit spending and the nation’s federal debt, which is the accumulation of all our deficits over time.

In this interview with Catalyst Editor William McKenzie, she explains the threat the debt poses to valuable programs like Social Security and Medicare but also to our ability to deal with over-the-horizon problems such as having enough dollars to educate a modern workforce. After working on fiscal issues for two decades, MacGuineas contends that controlling the debt must begin with strong political leadership.

Let’s start with some facts. What types of spending are really driving up the federal debt, which is now close to $23 trillion and grew 78 percent from 2010 thru 2019?

The biggest drivers on the spending side are without question the aging of the population and health care costs. Those two things have caused growth in our biggest programs — Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid — and they are eclipsing economic growth and are likely to do so going forward. Another factor putting upward pressure is we have been borrowing so much. Interest payments are now the fastest-growing part of our federal budget.

Your organization recently posted a piece about Congress considering several proposals that could reduce health care costs by as much as $900 billion over the next decade. For example, one proposal on your site is about limiting the rise of prescription drug prices to the inflation rate of Medicare and Medicaid. How feasible is that? How would it work?

This is feasible if they make it part of the regulatory process. There are arguments that it will have an impact on innovation and on the industry’s willingness to research new drugs. But those who finance the system, whether it is Medicare or insurers, can put limits on how much they will support the growing costs of prescription drugs. This is a place where there is bipartisan momentum. You might see some things coming along this spring.

Senators Mitt Romney, R-Utah, and Joe Manchin, D- West Virginia, are working on bipartisan legislation to deal with the trust funds that govern our highway spending as well as Medicare hospital spending. What is the significance of that effort?

The TRUST Act is one of the most exciting things going on up on the Hill. The bill is supported by a number of bipartisan, bicameral leaders who are fed up with kicking the can and ignoring the major problems in our largest programs such as Social Security and Medicare.

They have developed legislation that would require that anytime a trust fund gets out of balance, which is defined as being insolvent in the next 15 years, Congress must create a commission to study the issue and recommend solutions. It doesn’t say what those solutions are. I am sure the co-sponsors will have different ideas about them. But the bury-your-head-in-the-sand approach that Congress has taken on these big programs have left the programs so vulnerable and weak that they are going to really harm people who depend upon them if we don’t take measures to shore them up quickly.

The [TRUST Act] is supported by a number of bipartisan, bicameral leaders who are fed up with kicking the can and ignoring the major problems in our largest programs such as Social Security and Medicare.

Along these lines, there have been a number of proposals to change how we do federal budgeting. To what extent would changes in how we budget lead to some control of the debt?

Budget process could be the nudge that gets everything back on track, or it could be a total political punt.

A lot of people support budget process reform because they don’t want to deal with the underlying policy issue of what to do with spending and revenues. On the other hand, it could have profound effects. A lot of politicians want to do more on the issue. They face resistance from within their party, members of the other party, or within leadership, and budget process reform is a way to tip-toe into this area.

We should never allow our country to operate without a budget, which is something we do now. That is inconceivable. Even if you run a small company, you would be out in seconds if you suggested running your operation with no budget in place.

Even if you run a small company, you would be out in seconds if you suggested running your operation with no budget in place.

Our budget doesn’t have any real constraints, so a really good idea is to add debt targets for every year. You would have goals about what share of the economy the debt should be. Then, when the budget is presented by the White House and Congress, it would have to meet those goals. Legislators could fight about how you get there, but putting in place a fiscal goal like that could gradually drag us back in a healthy direction.

Another idea is that if they don’t pass a budget, which is more common in recent years, an automatic continuing resolution would go into effect so you don’t have to shut down the government. That is one of the stupidest, most self-defeating situations we have been falling into in recent years – you can’t agree at work so shut the operation down? This would not fly in any other company or sector.

Maya MacGuineas speaks to the media at the National Press Club in 2011, encouraging policymakers to "go big and develop a large-scale debt reduction package sufficient to stabilize the debt as a share of the economy." (Alex Wong/Getty Images)

Maya MacGuineas speaks to the media at the National Press Club in 2011, encouraging policymakers to "go big and develop a large-scale debt reduction package sufficient to stabilize the debt as a share of the economy." (Alex Wong/Getty Images)

What do you see happening on Social Security reform, where most answers like changing the retirement age are known but nothing happens?

The TRUST Act would push us because the Social Security trust funds are set to run out in the 15-year time window. The legislation would move us toward setting up a commission that would work on Social Security. The closer we get to the early 2030s, when Social Security will not have enough money to pay full benefits, the more urgent it becomes to fix the program. In fact, I think the window of opportunity to fix it in a really smart way already has closed.

We will address it sooner or later because we have to. But I still see so much demagoguery on the issue. People screaming that anyone who wants to fix Social Security wants to take money away from seniors. That couldn’t be further from the truth. Social Security reform has an abundance of ways to fix it on the revenue side, on the spending side, on the retirement age side, on the little bit of all of that, which is what I think we should do.

Every year we wait to address the problem, the more people who depend on Social Security become in jeopardy and the more draconian the solutions become. But I do not see the political will to fix it as it should be in the next couple of years. Hope springs eternal, but we are leaving people hanging out there who depend upon this important program.

Should we be thinking about stabilizing the debt versus reducing it significantly?

The objective used to be to balance the budget, and I wish we could be talking about that. But that goal is so far out of reach that we should not fool ourselves into thinking we will in the coming years. But we can stop this upward track of the debt’s share of the economy.

The share of the debt held by the public is projected to go from 79 percent of GDP now up to about 100 percent in the next 10 years. Instead, we could put it on a more reasonable glide path, where the debt as relative to the economy would grow more slowly and then ultimately start to come back down, possibly to about 60 percent of the economy. Many economists think this is a much more comfortable zone, and perhaps we could get it back to the historical average, which was below 40 percent of GDP.

The most important thing at this point is to flip the switch where the economy is growing faster than the debt. Now, the debt is growing faster than the economy. Its share of the economy is higher than at any point since right after World War II. And we brought it right back down after the war. Never in our history have we had a deficit this big when our economy is so strong.

We face a number of big challenges, such as adapting to a new economy, educating a new workforce, and facing new security threats. But our hands are tied behind our backs because we are overindebted.

We face a number of big challenges, such as adapting to a new economy, educating a new workforce, and facing new security threats. But our hands are tied behind our backs because we are overindebted.

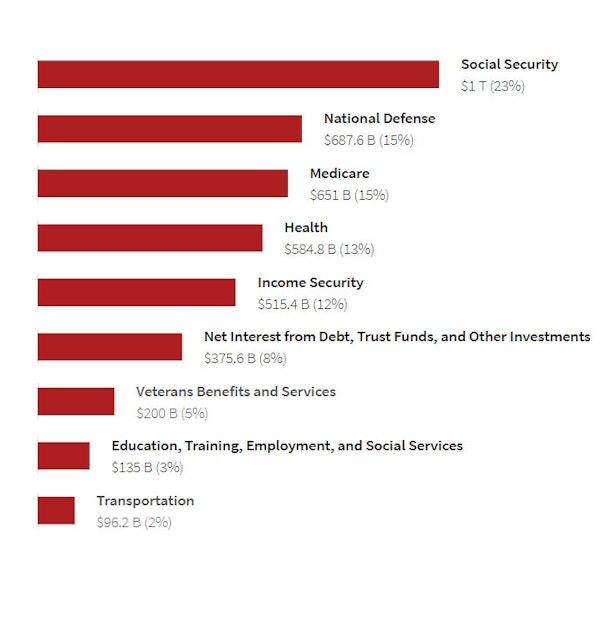

Current federal spending by category. (Source: usaspending.gov)

Current federal spending by category. (Source: usaspending.gov)

This problem of the debt and the deficit seems so much more impossible to grasp than, say, climate change, where a physical manifestation exists. How do you bring the realities of this challenge home so we can better understand it?

In the end, this will boil down to political leadership. This issue will not come up through the grassroots as so many other issues do. This will not be a message people want to hear. It doesn’t connect to their daily lives. And the solutions are hard. We are going to have to raise our taxes and cut our spending, plain and simple.

You have all sorts of political gymnastics to avoid those realities, but we won’t be able to fix it without those tough truths. We need political leadership, which hopefully is bipartisan, to make this a national issue that we can come together on. We need leaders who can explain why it matters and honestly lay out the solutions needed to fix it.

In the end, this will boil down to political leadership. … And the solutions are hard. We are going to have to raise our taxes and cut our spending, plain and simple.

I don’t recall the debt coming up in any of the recent Democratic debates. Has it?

There have been over 500 questions and not one of them has been about the national debt.

Where do you find encouragement when it comes to dealing with this issue?

Hundreds of members of Congress care about this issue and want to do the hard work it requires. Millions of people understand the importance of this subject and are willing to do something to fix it.

So, there is a group that is receptive to leadership on this issue. The big question is, will we see this leadership quickly, or will we have to wait until the possibilities of fixing this situation are fewer and fewer?

The Catalyst believes that ideas matter. We aim to stimulate debate on the most important issues of the day, featuring a range of arguments that are constructive, high-minded, and share our core values of freedom, opportunity, accountability, and compassion. To that end, we seek out ideas that may challenge us, and the authors’ views presented here are their own; The Catalyst does not endorse any particular policy, politician, or party.

-

Previous Article We Cannot Burden Future Generations with Unpaid Debts A Conversation with John Kasich, Former Governor of Ohio and Former Congressman (R-Ohio)

-

Next Article Our $23 Trillion National Debt: An Inter-generational Injustice An Essay by Michael A. Peterson, Chairman and CEO of the Peter G. Peterson Foundation