Why America’s Free Market Economy Works Better in Some Places than Others

Is America’s free market system working as advertised? Mostly yes, but it depends to a surprising degree on where you live.

The Research Triangle region of North Carolina is anchored by three major research universities: North Carolina State University, Duke University, and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The Research Triangle region of North Carolina is anchored by three major research universities: North Carolina State University, Duke University, and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

If it’s working right, the free market system produces goods and services better than any alternative. It creates powerful incentives to innovate, and generally ensures people’s earnings reflect the value they deliver to others through work. It also offers upward mobility to people who invest in their own “human capital” and work hard. (That said, the market economy doesn’t promise equal outcomes, since people’s contributions are invariably unequal.)

A market economy, however, depends on well-functioning markets. These include competitive product markets with relatively low barriers to new entrants, since firms facing little competition usually deliver poor quality and charge prices out of whack with people’s wages. Advanced market economies work best in places with “thick” labor markets, meaning large numbers of workers with rich varieties of skills and diverse employers. In today’s knowledge-centric economy, it also thrives in places with thick markets in ideas.

A successful economy, moreover, requires reasonably free markets in land use, so firms and individuals can efficiently connect in optimal locations. If regulations generate excessive housing costs or impede the dynamic adjustment of locations to their highest use as realities change, they clog up the markets for goods, labor, and ideas.

Well-functioning markets, in turn, depend on three foundations. First is ample provision of “public goods” by the public sector: a reliable legal system, quality public education from pre-K through college, and sound physical infrastructure. Attracting skilled workers also increasingly requires significant investment in quality-of-life amenities like greenspace, a lively arts scene, and walkable urban neighborhoods.

Second is a light-touch approach to public-sector intervention in the economy and competitive levels of taxation.

Third is strong “social capital” – that is, the dense fabric of relationships, civic engagement, voluntarism, and social cohesion that makes a community tick. Adam Smith famously wrote in The Theory of Moral Sentiments that trust and good-will among people are preconditions for a prosperous economy.

Today’s America features vast geographic variation in all these respects, and considerable variation in how well the economy is working for people.

If it’s working right, the free market system produces goods and services better than any alternative. It creates powerful incentives to innovate, and generally ensures people’s earnings reflect the value they deliver to others through work.

Competition in decline

The economy has seen a big increase in industrial concentration since the 1980s, especially in industries with large local presence like retail, construction, real estate, and broadband. Local governments in many places have contributed to concentration through restrictive land-use rules, subsidies to dominant firms, and policies blocking new entrants from the market. The result: higher prices, lower business investment, and less startup activity.

The hospital industry, for instance, has become much more concentrated in many cities just since 2010. Average prices for hospital services are now as much as 20 percent higher in the most concentrated markets than in less concentrated places, with equal or worse quality. More than 30 state governments, on the coasts but also in lower-income southern states, block new entrants through outdated “certificate-of-need” rules. Some have supported anti-competitive mergers by impeding federal antitrust reviews.

One of the most pernicious instruments used by state authorities is excessive occupational licensing rules. These rules, now covering 25 percent of the workforce, erect high barriers to entry by small-scale entrepreneurs in industries ranging from interior design to hair-braiding, sign-language interpreting, home entertainment setup, and solar-panel installation. They also block professionals like nurse practitioners and chiropractors from expanding the scope of their practice.

Excessive occupational licensing rules not only result in less competitive local markets but also in reduced geographic mobility of entrepreneurs. The wide variation in rules across states leads to lower upward mobility.

President Donald Trump hosts a working lunch with governors on “workforce freedom and mobility” in June 2019. President Trump spoke about the administration’s work to overhaul occupational licensing laws, job training programs and child care policies at companies around the country. (Alex Wong/Getty Images)

President Donald Trump hosts a working lunch with governors on “workforce freedom and mobility” in June 2019. President Trump spoke about the administration’s work to overhaul occupational licensing laws, job training programs and child care policies at companies around the country. (Alex Wong/Getty Images)

Studies by the National Conference of State Legislatures, the Reason Foundation, and the Institute for Justice agree the states suffering most from excessive licensing regulations include California, New York, West Virginia, and Louisiana, while the lightest-touch states include Minnesota, Colorado, Missouri, and South Carolina.

One acid test is new business formation. Based on U.S. Census data, metro areas that have achieved the fastest growth in businesses per capita over the last two decades include Minneapolis-St. Paul, Denver, Omaha, Salt Lake City, and Dallas-Fort Worth.

Big cities lead in markets for labor and ideas

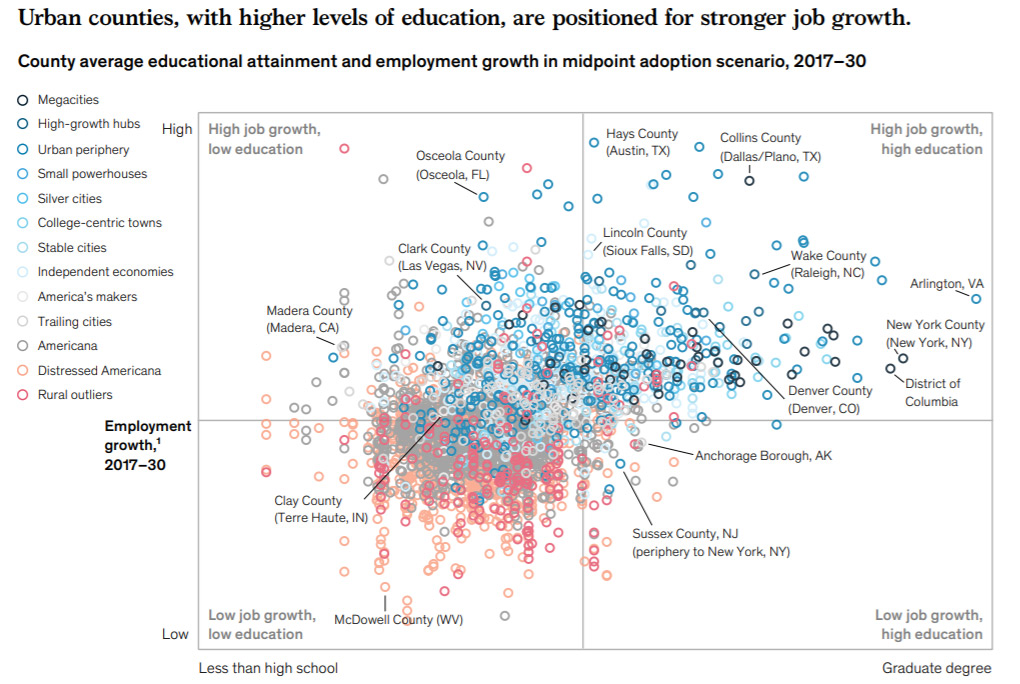

As the global economy becomes more knowledge-centric, a few large metros are increasingly pulling ahead of everyplace else, as McKinsey documents in a 2019 report. These include large metros dominating major sectors – New York in finance, the San Francisco Bay area and Seattle in technology – but also some 25 additional mega-cities with less glamorous but diverse industries and thick labor markets. The benefits these places enjoy from large size have been sufficiently powerful to offset the disadvantages some impose on themselves through excessive regulation and taxes.

Most smaller cities can’t match the biggest metros in the depth of their labor pool or their diversity of job opportunities. An additional challenge for many towns is dependence on a small number of local employers with the market power to hold down wages. One study by the Brookings Institution found that wages were 17 percent lower in places at the 75th percentile for employer concentration than in places at the 25th percentile, all else equal.

Permissive land-use rules help markets function

A number of metro areas score high for their relatively permissive land-use rules and also for success in building enough housing units to accommodate population growth, maintaining relatively good home affordability, and keeping average commute times manageable. These include the major metros in Texas, Colorado, and the Southeast; Minneapolis-St. Paul; Omaha; the three top Midwestern turnaround metros of Columbus, Indianapolis, and Pittsburgh; and (perhaps surprisingly) Washington, D.C.

On the other hand, New York City, Boston, and the principal metros of the West Coast operate especially restrictive land-use regimes and consequently suffer from sky-high home prices, business costs, and commute times. (Portland, Oregon, has enjoyed better home affordability than its West Coast peers, but is now experimenting with drastically tighter rules, with results to be determined.) One sure sign the economy is working poorly for many people in these places is the tremendous numbers leaving for more affordable places, despite high wages in the cities they’re leaving.

Foundations: public goods, economic freedom, social capital

U.S. cities vary considerably in their infrastructure, legal systems, educational attainment levels, and quality-of-life amenities. On one measure of educational attainment, the population share with a bachelor’s degree or higher within ethnic groups, top-performing metro areas include Boston, Raleigh, Durham, Minneapolis-St-Paul, Denver, and Washington, D.C. According to the Trust for Public Land’s widely-cited ranking of greenspace in U.S. cities, leading cities include Minneapolis, St. Paul, Denver, Portland, and Washington, D.C.

Denver, Colorado, is cited by the Trust for Public Land as a top U.S. city for green space. The city also received a high score from SMU economists on economic freedom.

Denver, Colorado, is cited by the Trust for Public Land as a top U.S. city for green space. The city also received a high score from SMU economists on economic freedom.

Places also vary widely on measures of government intervention and taxation. According to a measure of “economic freedom” calculated by SMU economists, places with high scores include the major Texas metros, Raleigh, Nashville, Omaha, Denver, and Washington, D.C. Metros in the Northeast, Midwest, and Far West mostly score much lower.

As for social capital, two studies agree that the states with strongest social capital measures are a contiguous cluster including Minnesota, the Dakotas, Nebraska, Montana, Utah, and Oregon, as well as the northern New England states of Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont.

One of these studies, from the U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee, drills down to the county level. According to the report, rural and small-town counties tend to have stronger social capital than big cities, but there are enormous differences across America’s large cities. Places with exceptionally robust social capital scores include Minneapolis-St. Paul, Denver, Omaha, Salt Lake City, Boise, Austin, Pittsburgh, Columbus, and Raleigh.

This report suggests, consistent with the message from the book Our Towns by James and Deborah Fallows, that there are a number of smaller cities in a sweet spot: small enough to sustain strong social capital but large enough to achieve the benefits of scale. These include cities like Grand Rapids, Michigan; Sioux Falls, South Dakota; and Greenville, South Carolina. This group also includes a number of urbanizing, high-growth suburban cities, in places like Fairfax County, Virginia (outside Washington), Collin County (outside Dallas), Fort Bend County (outside Houston), and Orange County (outside Los Angeles).

Public goods, economic freedom, and strong social capital are mutually reinforcing. Strong social capital in a community creates the basis for public-private coalitions to transform downtowns, improve parks, and fix ailing school systems. Weak social capital generates the conditions in which heavy-handed government intervenes excessively and counter-productively in the markets.

It may be that low-income levels in a place are correlated with low scores on all these measures. But, as Our Towns persuasively demonstrates, there are numerous smaller cities with relatively low median income but strong social capital that have overcome the odds and achieved successful turnarounds centered on public-goods investments.

Public goods, economic freedom, and strong social capital are mutually reinforcing. Strong social capital in a community creates the basis for public-private coalitions to transform downtowns, improve parks, and fix ailing school systems.

Effective markets deliver good economic outcomes

Based on growth in real GDP growth per worker and median household income growth since 2000 and on a measure of upward mobility from Harvard economist Raj Chetty, top-performing metros include a few big coastal metros (New York City, the Bay Area, Seattle, and Portland); the social capital and public goods stars (Minneapolis-St. Paul, Denver, and Omaha); the economic freedom stars (Texas metros plus Raleigh-Durham and Nashville); the leading Midwestern turnarounds (Columbus, Indianapolis, and Pittsburgh); and Washington, D.C.

In absolute dollar terms, people with an associate’s degree on average earn at least 50 percent more in high-performing metros than in low-performing ones. Bachelor’s degree holders earn more than twice as much. On Chetty’s measure, the income difference between high and low upward-mobility metros is more than 25 percent, controlling for race and the income of a person’s parents.

And people are voting with their feet. Big metros experiencing the largest inflows of migrants from elsewhere in America since 2000, relative to population, are the major metros of Texas, Colorado, and the Carolinas, along with Nashville, Tampa, Orlando, and Portland.

People are voting with their feet. Big metros experiencing the largest inflows of migrants from elsewhere in America since 2000, relative to population, are the major metros of Texas, Colorado, and the Carolinas, along with Nashville, Tampa, Orlando, and Portland.

The experience of these places shows the free market economy works well for people – provided a place gets the market fundamentals right.

Many states and localities could significantly improve the workings of product markets by re-examining policies blocking new entrants and constraining competition. Coastal and Deep South states, in particular, should focus on liberalizing excessive occupational licensing rules. Most big cities need to promote better housing affordability by freeing up land-use rules and embracing the growth of surrounding cities.

Smaller cities can partially overcome their labor market disadvantages by doubling down on their edge in affordability and investing in quality-of-life amenities, raising their attractions to skilled people pushed out of hyper-expensive coastal cities.

Finally, the free market economy thrives in places rich in social capital. For many American cities and towns, creating more trust and cohesion among local citizens – or building on the strong base that’s already there – may be the best investment they can make to deliver greater prosperity and opportunity for the people living there.

The Catalyst believes that ideas matter. We aim to stimulate debate on the most important issues of the day, featuring a range of arguments that are constructive, high-minded, and share our core values of freedom, opportunity, accountability, and compassion. To that end, we seek out ideas that may challenge us, and the authors’ views presented here are their own; The Catalyst does not endorse any particular policy, politician, or party.