On July 1, 2020, the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) becomes the law of the land, replacing the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

On July 1, 2020, the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) becomes the law of the land, replacing the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

When it was enacted in 1994, NAFTA created the largest free-trade region in the world. Since the start of NAFTA, North American firms have expanded and leveraged efficiencies of their regional supply chains to become more productive and competitive in the global economy.

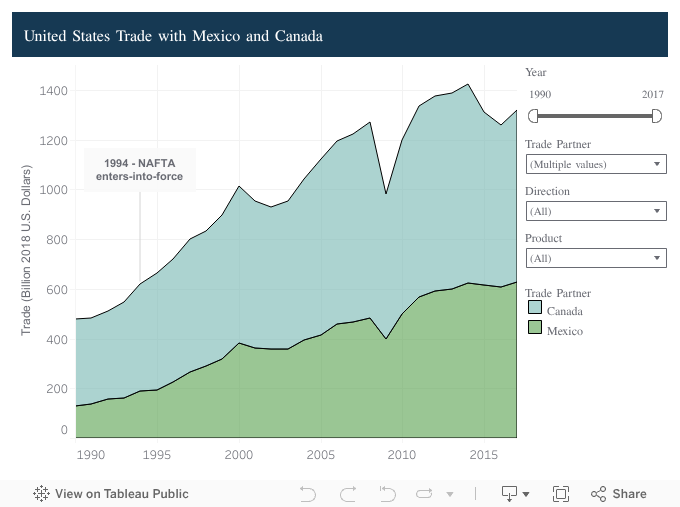

In 1990, the United States traded a little over $480 billion a year with Canada and Mexico. By 2017, the United States was trading over $1.3 trillion worth of goods and services (equal to 6.6 percent of U.S. GDP) every year with its two North American partners.

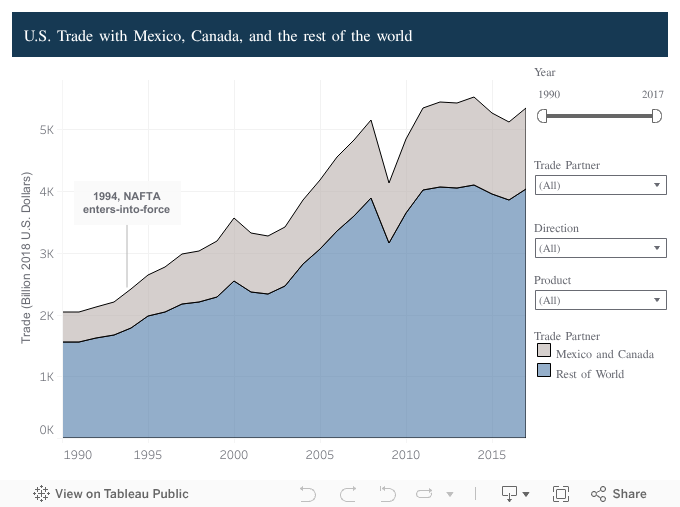

At the same time, U.S. trade outside North America expanded from $1.6 trillion to $4 trillion annually. Put another way, as our trade with our North American neighbors increased by about $820 billion, our trade with the rest of the world rose by $2.4 trillion, suggesting that integration has actually strengthened – and certainly has not reduced – our ability to compete in global markets.

Mexico and Canada have remained the United States’ largest trading partners. In fact, the U.S. exports more merchandise to Canada and Mexico than it exports to the rest of its top ten partners combined (including China, Japan, the United Kingdom, Germany, and South Korea).

Building off NAFTA’s success, USMCA improves access to the Canadian and Mexican markets for U.S. products and services, modernizes provisions for the digital age, and strengthens protection of intellectual property. It also strengthens the enforceability of labor and environmental regulations, moving us toward a more level playing field for attracting job-creating investments. From this perspective, USMCA largely reflects the structure and spirit of NAFTA, and represents a renewed commitment to North American economic integration.

Nonetheless, USMCA carries risks for regional competitiveness over the longer term. For example, USMCA adds regulations to the auto sector that will likely increase the cost of manufacturing vehicles in North America.

Since the U.S. auto industry relies heavily on continental supply chains, these cost increases will erode America’s ability to compete with European and Asian automakers in emerging markets such as Indonesia, Brazil, Nigeria, and China.

Apart from USMCA, the Chinese automotive industry is only in its early stages of growth – which means competition in the global automotive industry will intensify in the years ahead. If U.S. exports cannot remain cost-competitive in overseas markets, any gains from USMCA will not be sustainable.

With these factors in mind, the most important element of USMCA is the creation of a dozen tripartite consultative bodies designed to address these issues. For example, Chapter 26 of USMCA creates a Competitiveness Committee. Combined with the six-year review clause, which requires the three governments to affirmatively recommit to USMCA every six years, these committees are an opportunity to address issues that are holding back North American competitiveness, enabling USMCA to adapt to changing circumstances as NAFTA could not.