There are few places on earth someone can’t grab a Coke or buy a mobile phone. In fact, Coca-Cola is sold in every country but two and...

There are few places on earth someone can’t grab a Coke or buy a mobile phone. In fact, Coca-Cola is sold in every country but two and almost everyone in the world (even 80% of people in poor countries) has access to a mobile phone. Despite the wide availability of these products even in remote locations, why can’t most women in developing countries get a life-saving screening for cervical cancer? A test for early signs of cervical cancer needs only a few drops of vinegar and the sharp eye of a trained person, and can cost less than fifty cents. If the lesion is caught early, a woman’s life can be saved by freezing the cervical lesion off much like you would a wart. How can we make simple solutions in health as ubiquitous as the sugary solution we call Coke?

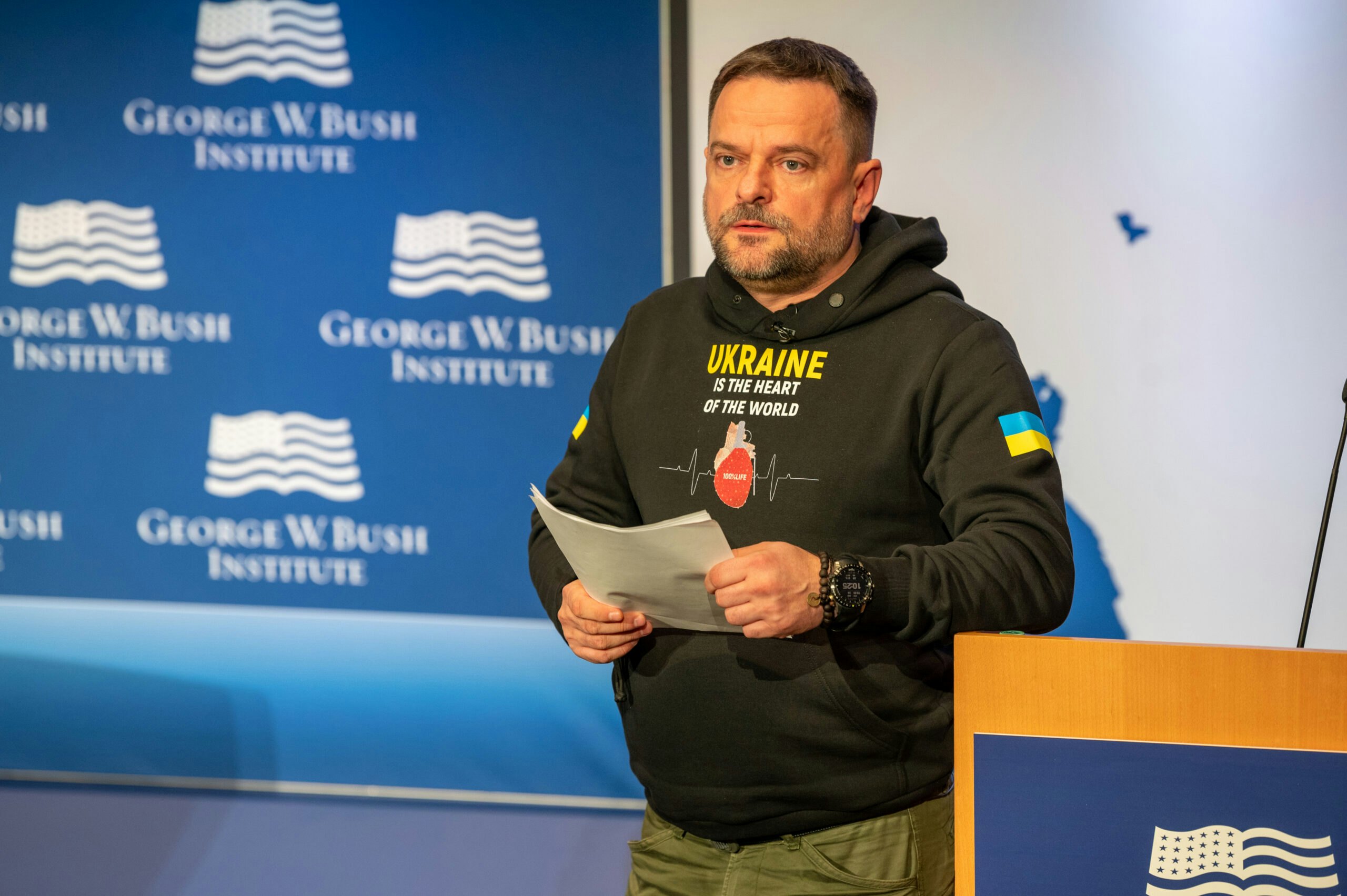

This oft overlooked parallel of accessibility opened Director of Global Health for the Bush Institute Dr. Eric G. Bing’s presentation to the Dallas Chapter of America’s Future Foundation Tuesday evening. Speaking before a crowd of Dallas area young professionals who meet to promote the belief that the marketplace is the best way to allocate resources, the recent co-author of Pharmacy on a Bicycle emphasized the role of proven business models in solving health problems at home and abroad.

According to Dr. Bing, “This is a global issue we must address with both research and action.” As it stands, 80 percent of Zambian women who develop cervical cancer eventually die from it. Yet, it can be easily prevented and treated once developed. Consider the rarity of death from cervical cancer in the United States.

A free market conversation evolved from postulations on policy into an emotional urgency when Dr. Bing spoke about his motivation to eradicate unnecessary deaths caused by cervical cancer. A visionary global health researcher, Dr. Bing shared the story of a young, poor woman. She was left abandoned as a baby and later worked as a domestic servant to support her children. Working tirelessly, she neglected light spotting, which eventually turned into heavy bleeding. When she finally saw a doctor, it was discovered she had cervical cancer, and that it had spread throughout her body. This woman – an American woman – died of an easily preventable and treatable condition. She was Dr. Bing’s mother.

His mother’s passing left Dr. Bing with a mission: to prevent and treat diseases that need not kill. To help ensure no mother is without access to affordable and simple health solutions.

On Tuesday, Dr. Bing solicited ideas from Dallas young professionals to advance his mission. In Zambia – a country with nearly 13 million people – there are only 45 gynecologists, of whom only one is a formally-trained cancer surgeon. Dr. Bing asked, “how can we use free market ideals to solve this?”

On a normal Tuesday evening, many young professionals talk about sports and hopeful weekend ventures. But with purpose and an inspired desire to provide “freedom from disease” for the poor, the Dallas AFF engaged in an action-oriented discussion. Professionals from a diverse set of backgrounds, education and employment expressed ideas and formulated solutions: create incentives, encourage private investment, promote public-private partnerships, and train Zambians who are not formal doctors to screen for cervical cancer – a lifesaving medical procedure that takes two weeks and no literacy skills to master.

Under the direction of Dr. Bing, the Bush Institute is incorporating many of these free market ideals in its Pink Ribbon Red Ribbon (PPPR) initiative, a public-private partnership that aims to save women from cervical and breast cancer in Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America. Programs such as PPPR are having an impact, but there is much work to be done. We cannot stop until every life is saved from easily preventable and treatable diseases like cervical cancer.

Under current conditions, estimates show it would take over a decade to screen every Zambian woman between 30 – 49 year old for cervical cancer, at a great cost and reliance on government and donors. Simple free market solutions can change this. Efficiency can save a nation. We need to continue finding ways to make something as important as a cervical cancer screening as accessible as a Coca-Cola and a cell phone.

This will take motivated individuals from a multitude of places, which is why the Bush Institute will continue to engage across the globe and within its own backyard. Efficiency and the free market can improve health access and save countless women – perhaps even your mother.

So the next time you pop open a Coke think to yourself, “what simple solution can save a life?”

Have ideas on making cervical cancer screenings more accessible in countries like Zambia? Tweet them using #OnaBike or post them at pharmacyonabicycle.com

Patrick Kobler is a member of the George W. Bush Institute's Education Reform Initiative and a board member of the Dallas Chapter of America’s Future Foundation. You can follow him on Twitter at @patrickkobler.