Veterans Can Fill the Skills Gap

As we analyze how to create new jobs, we also should be addressing the skills needed to fill those positions. Veterans are equipped to tackle these challenges. By tapping this valuable resource, we strengthen our economy.

Hull Technician 3rd Class Mark D. Knappenberger fabricates a doorframe aboard an amphibious assault ship. (Jered C. Wallem/U.S. Navy)

Hull Technician 3rd Class Mark D. Knappenberger fabricates a doorframe aboard an amphibious assault ship. (Jered C. Wallem/U.S. Navy)

Politicians like to talk about creating more jobs, but they do not necessarily like to talk about finding skilled workers for those jobs. This is not an either-or challenge. The lack of skilled workers in the United States is as much a reality as the need to create more jobs.

This reality will remain a problem for the foreseeable future. From manufacturing to health care, truck driving to plumbing, employers lack the talent for their jobs, which, in turn, limits economic productivity. After all, companies produce fewer goods and services when they lack workers with the right skills.

From manufacturing to health care, truck driving to plumbing, employers lack the talent for their jobs, which, in turn, limits economic productivity. After all, companies produce fewer goods and services when they lack workers with the right skills.

The U.S. manufacturing sector is often the target of promises to bring jobs back, but it actually suffers from a pretty severe skills gap. Deloitte and the Manufacturing Institute expect that two million manufacturing jobs will go unfilled in the next decade unless something changes. These jobs represent the “new manufacturing,” which requires higher skills and education than our parents and grandparents needed. Modern manufacturing requires engineers, computer scientists, and mathematicians.

Consider also the health care industry. Its persistent shortage of labor will continue to get worse at the same time the field is projected to grow 1.8 percent annually over the next five years.

Similarly, the American Trucking Association reports that 48,000 truck driving jobs are available. The barrier to entry into driving trucks may not be as high as getting into STEM fields, but this is a steady career with growth and pays well for the skill set.

Logistics positions also are tied to the transportation industry. Amazon has vowed to hire 100,000 people in the next 18 months, and they aren’t the only ones. Yes, many of these positions are entry level, but they also need managers and senior managers.

Veterans are ready

Veterans are well-positioned to fill these vacancies, just as addressing immigration policies in the short term and strengthening the education pipeline over the long term would help fill the void. These numbers underscore a steady flow of potential workers:

Military job fair (Sandy Huffaker/Getty Images)

Military job fair (Sandy Huffaker/Getty Images)

- The U.S. has approximately 3.2 million post-9/11 veterans;

- More than one million of them are in college;

- 100,000 veterans graduate from college every year;

- Two-thirds of veterans are leaving their first post-military job within two years; and

- 250,000 service members, including enlisted men and women and officers, will transition out of the military every year for the foreseeable future.

Existing policies, however, are not effective in preparing enough veterans for these jobs. Targeted changes to the Post-9/11 GI Bill and military-transition initiatives would address this deficiency.

Probably the best known program to train and educate veterans is the GI Bill. The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 — the original GI Bill — is the vehicle through which hundreds of thousands of returning service members financed college educations and started businesses after World War II. A resounding success, the GI Bill helped postwar veterans obtain the skills and education to re-enter the workforce and grow the middle class.

The Post-9/11 GI Bill has similar aims but a broader reach, wisely allowing veterans to use the benefits for trade schools and other non-traditional education. It also has similar positive economic impacts. Early reports are finding a possible $8 return for every $1 spent.

Yet the bill needs modernizing. For example, benefits end upon completing a four-year degree. Contrast that with the labor demands in the fields of science, technology, engineering, and math. STEM jobs require more education than a four-year degree.

Three recommended changes

By being more flexible, the Post-9/11 GI Bill could expand veterans’ access to the type of training they need to fill these good, in-demand jobs. Adding a fifth year would help veterans receive the advanced degrees they need to compete in these markets.

By being more flexible, the Post-9/11 GI Bill could expand veterans’ access to the type of training they need to fill these good, in-demand jobs. Adding a fifth year would help veterans receive the advanced degrees they need to compete in these markets.

Modernizations like these could be financed through returning the Post-9/11 GI Bill, and state-sponsored measures like Texas’s Hazelwood Act, to their roots of serving veterans. Benefits have cost significantly more than expected as they have expanded to include the spouses and children of veterans. Focusing on only veterans would keep these programs financially sustainable and flexible enough to expand services to the population they were intended to serve.

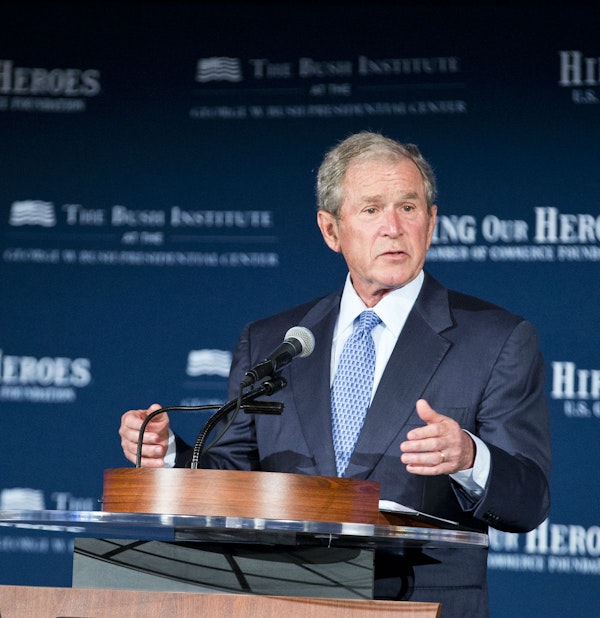

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation’s Hiring Our Heroes program and the George W. Bush Institute’s Military Service Initiative hosted "Mission Transition" on June 24, 2015 in Washington, DC. (Rebecca Emily Drobis/United States Chamber of Commerce)

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation’s Hiring Our Heroes program and the George W. Bush Institute’s Military Service Initiative hosted "Mission Transition" on June 24, 2015 in Washington, DC. (Rebecca Emily Drobis/United States Chamber of Commerce)

This also brings up changes to the Post-9/11 GI Bill that would help get veterans into the trades, another area facing labor shortages. The U.S. Department of Education needs to streamline the process of accrediting trade schools that serve returning veterans. Trade schools can make them marketable in as little as three months, but some schools have been waiting years to become eligible for funding under the legislation.

The U.S. Department of Education needs to streamline the process of accrediting trade schools that serve returning veterans. Trade schools can make them marketable in as little as three months, but some schools have been waiting years to become eligible for funding under the legislation.

Improve hiring initiatives

Hiring initiatives need reforming, too. Hundreds of hiring initiatives in both the public and private sectors have formed since 9/11, with varying degrees of success. For the most part, successful programs have inculcated a culture within their organization to value the adaptive skills, work ethic, and moral character that veterans bring to the workplace.

We should use taxpayer dollars to train veterans so they are ready to take advantage of those initiatives. For example, at the end of a service member’s tenure, they should receive time off for training in a trade like welding, if that is the career they want to pursue. Or they should be guided through the education process so they can be informed enough to make college decisions once they exit the military. They spend three months in boot camp at the outset; why not ample time at the end of their service to prepare for the next step?

What’s more, the military often hires veterans who only recently left service themselves, or have little civilian work or education experience, to guide warriors making the transition into civilian life. Universities, non-profits, and, more importantly, businesses are eager to share their expertise as they try to recruit returning veterans. Capitalizing upon their willingness to help would be a smart addition and have a positive impact on both service members and the Pentagon’s budget.

To be sure, some bases are being innovative about helping with transitions. One great example is the use of temporary duty assignment. TDAs provide service members such options as working for companies, securing internships, and attending trade schools, while still serving on active duty and being paid by the military.

These alternatives make them more employable after they leave the service. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce fellowship, Camp Pendleton’s relationship with Workshop for Warriors, and the United States Special Operations Command Warrior Care Program are among the programs with a proven record. They should be expanded and adopted by all branches of the military.

The programs currently in place to assist veterans make their transitions are not perfect, but they are a great foundation to build upon. Reforms to each of them will ensure that they empower veterans to make smart education and training decisions.

This is all part of equipping the veteran population to help fill the skills gap. After serving their country in the military, they now are ready to take on the challenge of helping employers find the talent they need. After serving their country in uniform, they now are ready to take on the challenge of economic productivity.

The Catalyst believes that ideas matter. We aim to stimulate debate on the most important issues of the day, featuring a range of arguments that are constructive, high-minded, and share our core values of freedom, opportunity, accountability, and compassion. To that end, we seek out ideas that may challenge us, and the authors’ views presented here are their own; The Catalyst does not endorse any particular policy, politician, or party.

-

Previous Article The Evolving Volunteer Force An Essay by Tim Kane, Author of Bleeding Talent and J.P. Conte Fellow in Immigration Studies at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University

-

Next Article A Pipeline of Leaders An Essay by Colonel Miguel Howe, USA (Ret.), Director, Military Service Initiative, George W. Bush Institute